Mokele-mbembe

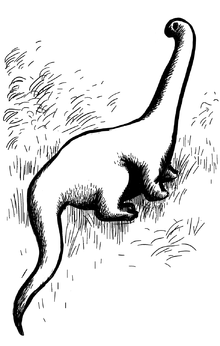

In Congo River Basin mythology, Mokele-mbembe (Lingala: mókɛlɛ ᵐbɛ́ᵐbɛ, "rainbow"[1]) is a water-dwelling entity, sometimes described as a living creature, sometimes as a spirit.

During the early 20th century, descriptions of the entity increasingly reflected public fascination with dinosaurs, including aspects of particular dinosaur species now known among scientists to be incorrect, and the entity became increasingly described alongside a number of purported living dinosaurs in Africa.[2]

Over time, the entity became a point of focus in particular among adherents of the pseudoscience of cryptozoology, and young Earth creationism, resulting in numerous expeditions led by cryptozoologists and funded by young Earth creationists and groups with the aim of finding evidence that invalidates scientific consensus regarding evolution. Paleontologist Donald Prothero remarks that "the quest for Mokele Mbembe ... is part of the effort by creationists to overthrow the theory of evolution and teaching of science by any means possible".[3] Additionally, Prothero observes that "the only people looking for Mokele-mbembe are creationist ministers, not wildlife biologists."[4]

Historian Edward Guimont has argued that the mokele-mbembe myth grows out of earlier pseudohistorical claims about Great Zimbabwe, and in turn influenced the later reptilian conspiracy theory.[5]

History

1909 saw the first mention of an apatosaurus-like creature in Beasts and Men, the autobiography of famed big-game hunter Carl Hagenbeck. He claimed to have heard from two independent sources about a creature living in Rhodesia which was described to them by natives as "half elephant, half dragon."[6] Naturalist Joseph Menges had also told Hagenbeck about similar stories. Hagenbeck speculated that "it can only be some kind of dinosaur, seemingly akin to the Brontosaurus."[6] Another of Hagenbeck's sources, Hans Schomburgk, asserted that while at Lake Bangweulu, he noted a lack of hippopotami; his native guides informed him of a large hippo-killing creature that lived in Lake Bangweulu; however, as noted below, Schomburgk thought that native testimony was sometimes unreliable.[7]

Reports of entities described to be dinosaur-like in Africa caused a minor sensation in the mass media, and newspapers in Europe and North America carried many articles on the subject in 1910–1911; some took the reports at face value, others were more skeptical.

According to German adventurer Lt. Paul Gratz's account from 1911:

The crocodile is found only in very isolated specimens in Lake Bangweulu, except in the mouths of the large rivers at the north. In the swamp lives the nsanga, much feared by the natives, a degenerate saurian which one might well confuse with the crocodile were it not that its skin has no scales and its toes are armed with claws. I did not succeed in shooting a nsanga, but on the island of Mbawala I came by some strips of its skin.[8]

Another report comes from German Captain Ludwig Freiherr von Stein zu Lausnitz, as described by Willy Ley in Exotic Zoology (1959). Von Stein was ordered to conduct a survey of German colonies in what is now Cameroon in 1913. He heard stories of an enormous reptile called "Mokéle-mbêmbe" alleged to live in the jungles, and included a description in his official report. According to Ley, "von Stein worded his report with utmost caution," knowing it might be seen as unbelievable.[9] Nonetheless, von Stein thought the tales were credible: trusted native guides had related the tales to him, and the stories were related to him by independent sources, yet featured many of the same details. Though von Stein's report was never formally published, Ley quoted von Stein as writing:

The animal is said to be of a brownish-gray color with a smooth skin, its size is approximately that of an elephant; at least that of a hippopotamus. It is said to have a long and very flexible neck and only one tooth but a very long one; some say it is a horn. A few spoke about a long, muscular tail like that of an alligator. Canoes coming near it are said to be doomed; the animal is said to attack the vessels at once and to kill the crews but without eating the bodies. The creature is said to live in the caves that have been washed out by the river in the clay of its shores at sharp bends. It is said to climb the shores even at daytime in search of food; its diet is said to be entirely vegetable. This feature disagrees with a possible explanation as a myth. The preferred plant was shown to me, it is a kind of liana with large white blossoms, with a milky sap and applelike fruits. At the Ssombo River I was shown a path said to have been made by this animal in order to get at its food. The path was fresh and there were plants of the described type nearby. But since there were too many tracks of elephants, hippos, and other large mammals it was impossible to make out a particular spoor with any amount of certainty.[10]

Alfred Aloysius Smith, who had worked for a British trading company in what is now Gabon in the late 1800s, briefly mentions in his 1927 memoir the "jago-nini" and "amali":

Aye, and behind the Cameroon there's things living we know nothing about. I could 'a' made books about many things. The Jago-Nini they say is still in the swamps and rivers. Giant diver it means. Comes out of the water and devours people. Old men'll tell you what their grandfathers saw but they still believe its there. Same as the Amali I've always taken it to be. I've seen the Amali's footprint. About the size of a good frying pan in circumference and three claws instead of five.

He also speculates that "some great creature like the Amali" could be responsible for finding broken and splintered ivory in (now known to be mythical) elephants' graveyards,[11] as well as claiming to have given a chiseled out cave painting of the amali to Ulysses S. Grant.[12]

In 2001, BBC broadcast in the TV series Congo a collective interview with a group of BiAka pygmies, who identified the mokele mbembe as a rhinoceros while looking at an illustrated manual of wildlife.[13] Neither species of African rhinoceros is common in the Congo Basin, and the Mokèlé-mbèmbé may be a mixture of mythology and folk memory from a time when rhinoceroses were found in the area.

In August and September of 2018, Lensgreve of Knuthenborg, Adam Christoffer Knuth, along with a film crew from DR and a DNA scientist, traveled to Lake Tele in Congo, in search of the Mokele-mbembe. They did not find the dinosaur. However they found a new green algae, which has not been discovered before.[14][15]

In 2016, a young travel documentary crew, from South Africa, made an independent documentary about searching for Mokele-mbembe, which they later sold to Discovery Africa.[16][17] The team, consisting of Jordan Deall, Luke Macdonald, and Donovan Orr, spent roughly four weeks in the Likuoala swamp region visiting various Aka (pygmy) villages, collecting stories of the creature's existence. Whilst they point out the difficulty of differentiating between Mokele-Mbembe's spiritual and physical existence, they interviewed numerous people who believe in its presence, whilst others suggest the last of the species died at least a decade ago.[18]

References

- Roy P. Mackal (1987). A Living Dinosaur? In Search of Mokele-Mbembe. New York: E.J. Brill.

- Loxton & Prothero (2013), p. 266–267.

- Loxton & Prothero (2013), p. 262–295.

- Prothero (2015), pp. 233–235.

- Guimont, Edward (18 March 2019). "Hunting Dinosaurs in Central Africa". Contingent Magazine. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Hagenbeck, Carl (1912) [1909]. Beasts and Men. Translated by Elliot, High S. R.; Thacker, A. G. London, England: Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 95–97 – via Internet Archive.

- "History of Mokele Mbembe And Expeditions To Africa". The Daily Journalist.

- Green, Lawrence G. (1961). "12: Graetz of the Great North Road". Great Road North. pp. 201–202 – via Internet Archive.

- Ley (1959), p. 69.

- Ley (1959), p. 70.

- Young, Rory (15 November 2013). "Do Elephant Graveyards Exist?". Slate. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Horn, Alfred Aloysius (1927). Lewis, Ethelreda (ed.). Trader Horn. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. pp. 257-258 – via Internet Archive.

- "Spirits of the Forest - min 45:00". BBC.

- Almbjerg, Sarah Iben (28 November 2018). "Uimodståelig Dino-jagt på DR2". Berlingske (in Danish). Berlingske Media. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Madsen, Fie West (28 November 2018). "Lensgreve Christoffer Knuth har brugt kæmpe summer på vild dinosaur-jagt: 'Vi fandt noget, som ingen har set før'". BT.dk (in Danish). Berlingske Media A/S. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Cowen, Nick. "Backpacking Into the Unknown". The Citizen. The Citizen. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Editor, Show. "New On TV Today". TVSA. TVSA. Retrieved 4 October 2019.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- hitched, Congo. "hitched.congo Webseries". hitched series. Tomfoolery TV. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

Further reading

- Loxton, Daniel; Prothero, Donald R. (2013). Abominable Science: Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and other Famous Cryptids. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52681-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prothero, Donald R. (2015). The Story of Life in 25 Fossils: Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of Evolution. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-53942-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ley, Willy (1959). Exotic Zoology. Viking Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)