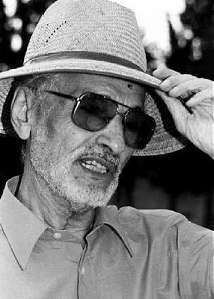

Mohamed Chafik

Mohamed Chafik (Berber languages: ⵎⵓⵃⵎⵎⴰⴷ ⵛⴰⴼⵉⵇ ), born 17 September 1926, is a leading figure in the Amazigh (also known as Berber) cultural movement. An original author of the Amazigh Manifesto, he was later appointed as the first Rector of the Royal Institute of the Amazigh Culture. He has worked extensively on incorporating Amazigh culture into Moroccan identity and is a leading intellectual of the Moroccan intelligentsia.

Mohamed Chafik ⵎⵓⵃⵎⵎⴰⴷ ⵛⴰⴼⵉⵇ محمد شفيق | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 17, 1926 Bir Tam-Tam, Aït Sadden (near Fes), Morocco |

| Occupation | Professor, First Rector of the IRCAM |

| Nationality | Moroccan |

| Notable works | Amazigh Manifesto, Arabic-Amazigh Dictionary, A Brief Survey of Thirty-Three Centuries of Amazigh History |

| Notable awards | Prince Claus Award |

| Moroccan literature |

|---|

| Moroccan writers |

|

| Forms |

|

| Criticism and awards |

|

| See also |

|

Early life and education

Mohamed Chafik was born in the small village of Béni Ait Sadden, located in the Middle Atlas mountains. He was raised in a devout Muslim household by his wealthy agricultural family. At the age of 8 he began his French language education. He would later describe this as "The third of my socio-cultural dimensions: my marocanity", referring to the addition of French to his language repertoire, which previously consisted of Arabic and Amazigh.[1] Chafik then enrolled at the elite collège d'Azrou. There he was taught by My Ahmed Zemmouri, who was a proponent of Moroccan independence from France. He finished his secondary education at the lycée Moulay Youssef, now infamous for its temporary closure due to student protests that erupted in 1944. During the political tensions surrounding Moroccan independence, Chafik avoided conscription, unlike many of his other graduating classmates from the collège d'Azrou. Despite interruptions of his education due to political strife, he would go on to receive degrees in Arabic, Amazigh, history, and pedagogy.[2]

Professional work and Amazigh activism

Early work

Before committing to the revival and re-appreciation of Amazigh culture, Chafik held a number of other positions that would prove to be helpful to him in the future. He began his career as a teacher in the mid 1950s. In particular, he worked to educate girls of rural areas, as they traditionally had limited access to education.[3] In 1955 he was appointed Inspector of Primary Education.[4]

From the 1960s into the 1970s, he was promoted through the ranks of Moroccan civil service. In 1963 he was promoted from Inspector of Primary Education to First Inspector of National Education. In 1970 he was named Secretary of Education in the royal cabinet and in 1972 he became Secretary of State to the Prime Minister. From 1973 to 1976 was again an adviser to the Royal Court after which he was appointed director of the Collège Royal. There he taught the current king of Morocco, Mohammed VI.[5] During his time in these posts he advocated for strong multilingual education, but gained little traction in the face of hegemonic French.[3]

During this time as well, he wrote extensively about the central place that the Amazigh peoples occupy in Moroccan and African culture. He stressed the importance of using an intersectional lens to look at the ethnic and linguistic complexities of Morocco. In this vein, he is noted for reconciling the views of Arab-nationalists and Islamists. Abdesslam Yassine, a staunch Islamist with whom he frequently disagreed, was a colleague he worked with in the Ministry of Education. Yassine used the argument that Islamic-Arab identity of Morocco is tied intrinsically to qu'ranic Arabic and therefore argued against the introduction of Amazigh to Morocco's education system. Chafik pointed out that Morocco is not a purely Arab nation and nor is Islam solely compatible with Arab identity. Without rejecting Islam or Arabic, Chafik retorted that there was no justification for the suppression of Amazigh language in the Quran, citing the verse that reads "the Arab is no better than the foreigner, nor the foreigner than the Arab but in piety."[2]

In 1980 Chafik co-founded l’Association culturelle amazighe (the Amazigh Culture Association). This was the first of its kind to use the preferred term 'Amazigh' instead of the exonym 'Berber'. Chafik advocated for this terminological change to reflect the Amazigh people's self-identification. The word 'Berber' comes from Latin for barbarian, which in itself is pejorative, while 'Amazigh' literally translates to 'the free people'. Unfortunately, the Association was short lived. In 1982 the association's leader, Sidqi Azayko, was arrested and imprisoned for a year. This prompted Chafik and his colleagues to suspend the association.[6] This did not deter the activists and Chafik continued to advocate by writing essays and extensive lobbying. In the same year that he co-founded the Association he was also appointed to a position at l'Académie du Royaume du Maroc (Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco).[5]

The Manifesto and IRCAM

The year 2000 was the most significant year for the Amazigh cultural movement. It was in this year that Chafik wrote and presented 'Un manifeste pour la reconnaissance officielle de l’amazighité du Maroc', more commonly known as the Amazigh Manifesto. It was in this manifesto that he laid out a nine-point argument for the promotion of Amazigh language and culture and demanded official recognition from the Moroccan Government. The manifesto was signed by over two hundred other activists, writers, and Amazigh artists.[2]

The manifesto proved to be influential, as on 17 October 2001, not even one year later after its publication, King Mohammed VI established by dahir the Royal Institute of the Amazigh Culture (IRCAM). Chafik would later be named the first rector of the institute. However, he declined a salary to prove his complete dedication to the cause. One of the first issues addressed by the institute was the standardization of the Amazigh orthography.[7] There was little consensus on how to approach a standard orthography, as many Arab-nationalists lobbied for the use of Arabic script. Chafik and many other Amazigh scholars identified this as problematic, as it would further a hierarchy among the languages. Chafik argued for creating and standardizing an Amazigh script while seeking comprise in its implementation. He offered that schools should teach this script along with the Latin alphabet for French and the Arabic adjad for Arabic. While controversy still surrounds the teaching of Amazigh in schools,[8] another dahir of Mohammed VI officially recognized the Tifinagh script, an important victory for the Amazigh cause.[9]

Even with the establishment of IRCAM, many leaders within the institute continued to disagree. Many of the more militant Amazigh scholars felt that government oversight of the institute would lead to the manipulation and perversion of their vision of promoting Amazigh culture. The officials more closely allied with the Moroccan government argued that the chances to accomplish any goals would drastically diminish without government funding and supervision. Chafik fell somewhere in the middle of these two camps. Having worked with both groups at one time or another, he frequently sought compromise. However, in February 2005 controversy struck when seven leading officials resigned. They claimed that IRCAM was serving the agenda of the government and Palace more than that of the Amazigh community. Ultimately, Chafik sided with the government but was sympathetic to their grievances.[2]

Retirement

In November 2003 Chafik retired from his post as director of IRCAM. He chose his colleague Ahmed Boukouss to fill the vacancy. During the 2000s he spent little time in the public eye except to give occasional interviews. However, he reappeared again in 2011 to co-author and sign an open letter to the Moroccan government concerning the constitutional referendum of July that year. While elevating the Amazigh language to official status was in the referendum draft, the letter clearly outlined the expectations of the government in recognizing Amazigh as an official national language. Chafik was the first to sign the letter and the government did in fact clarify the provision for Amazigh's official status.[10] Chafik still holds his position as a member of the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco.[5]

Awards and honor

In 1972 the Ordre des Palmes Académiques bestowed Chafik with the title of chevalier for his work as a francophone intellectual.[5]

In 2002 the Prince Claus Fund[11] awarded Chafik the Principal Award (Laureate) for his academic achievements, specifically due to the large Amazigh population in The Netherlands.

In 2014, during the 15th Throne Celebration of Mohammed VI, the king honored Chafik with a royal wissam with the distinction of Al Kafaa Al Fikria for intellectual merit.[12]

In 2018, on April 26, Chafik was honored with the Prix de la Fondation de l'Académie du Royaume du Maroc at the closing of their 45 session. The honor paid homage to Chafik's life accomplishments and contributions to the Moroccan cultural landscape.[13]

Major works

- Pensées sous-développées (Underdeveloped Thoughts), 1972, Librairie-papeterie des écoles, Rabat.

- Ce que dit le muezzin (That which the Muezzin says), 1974, Librairie-papeterie des écoles, Rabat.

- Aperçu sur trente-trois siècles d’histoire des Amazighs (A glimpse of thirty-three centuries of Amazigh history) , 1989, Alkalam, Mohammedia.

- Dictionnaire bilingue : arabe-amazigh (Arabic-Amazigh Bilingual Dictionary), tome 1 (1990), tome 2 (1996), tome 3 (1999), Publications de l’Académie marocaine.

- Quarante-quatre leçons en langue amazighe (Forty Four lessons in Amazigh), 1991, Édition arabo-africaine, Rabat.

- Le dialecte marocain : un domaine de contacte entre l’amazigh et l’arabe (The Moroccan dialect: a field of confluence between Amazigh and Arabic Languages), 1999, publication de l’Académie marocaine, Rabat.

- La langue tamazight et sa structure linguistique (The Amazigh language and its linguistic structure), 2000, Le Fennec, Rabat.

- Pour un Maghreb d’abord maghrébin (For a Maghreb that is first maghrebian), 2000, Centre Tarik Ibn Zyad, Rabat.

See also

- Royal Institute of the Amazigh Culture

- Berber orthography

References

- "Wikiwix's cache". archive.wikiwix.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce (2011). The Berber Identity Movement and the Challenge to North African States. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- "Wikiwix's cache". archive.wikiwix.com. Archived from the original on 2007-07-17.

- "M. Chafik : les dégâts de l'élite sont enormes". Economia (in French). 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- "Académie du Royaume du Maroc : أكاديمية المملكة المغربية". www.alacademia.org.ma. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- "Wikiwix's cache". archive.wikiwix.com. Archived from the original on 2006-11-16.

- "Amazigh World : Breves informations". Archived from the original on 2007-08-04.

- Lindsey, Ursula (27 July 2015). "The Berber Language: Officially Recognized, Unofficially Marginalized? - Al-Fanar Media". Al-Fanar Media. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

- LARBI, Hsen (March 14, 2003). "Which Script for Tamazight, Whose Choice is it ? - TAMAZGHA le site berbériste". www.tamazgha.fr. 12 (2). Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- "Mohamed Chafik : homme de pensée et de combat berbère". Le Matin d'Algérie (in French). Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development Archived 2007-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "15ème anniversaire de la Fête du Trône". Maroc.ma (in French). 2014-07-28. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- "La Fondation de l'ARM rend hommage à Mohamed Chafik – La Nouvelle Tribune". La Nouvelle Tribune (in French). 2018-04-30. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

External links

- Interview with Mohamed Chafik in TelQuel-Online by Driss Ksikes (in French): "L'Islam prône la Laïcité"