Mock language

Mock language is a term in linguistic anthropology for the intentional use of a language not spoken by or native to the speaker that is used to reinforce the speaker's language ideology of the hegemonic language.

When talking, the speaker includes words or phrases from other languages that they think fit into the conversation. The term "Mock Spanish" was popularized in the 1990s by Jane H. Hill, a linguist at the University of Arizona, mock Spanish is the most common form of mock language in the southwestern United States, where Hill first researched the phenomenon.[1] The term "Mock" has since been applied to other languages, and the umbrella term "Mock language" developed. Mock language is commonly viewed as a form of appropriation. In the United States, the most common form is mock Spanish. However, globally, mock language is used to share meaning between the speaker and audience about the speech community the speaker is mocking.

Definition

The speaker is unintentionally indexing a language ideology that all Americans should speak English or that other languages are secondary in the US. Using words outside the speaker's native language neglects context of the conversion, meaning of the word or phrase, or conceptual knowledge including historical injustices to the borrowed language, culture, and physical surroundings. It is a borrowing words in different languages and using it in your context.

When using mock language, the speaker is showing his 'cosmopolitanism' or global knowledge. One dominant language ideology is that English should be the only language spoken in the United States, establishing English as a hegemonic language. This hegemony[2] creates a dominance of the hegemonic group over the ones that have not conformed. Mock language reinforces this, as it takes language and culture out of context to show the speaker's worldly knowledge, but does not celebrate or intellectually use the language. This ideology is actually maintaining the subordinate status of the other languages used as the language speakers in that community are expected to speak English and not in a mocking way.

For the opposing perspective, saying that using other languages in an English conversation is supportive of that language, it does not show awareness of the cultural or social meanings behind the words spoken.

History, Theorists, and Contributors

The term "Mock Spanish" was popularized in the 1990s by linguistic anthropologist Jane H. Hill. This led to other languages being referred to as "Mock-Languages." Increasing globalization in modern history has contributed significantly to the spreading and study of Mock-Language in linguistic anthropology. Globalization has occurred at an exponential rate through numerous media—such as television and social networking applications—during the turn of the 21st century. With globalization, more languages are being encountered in daily interactions, and more people are able to travel. To show this global perspective, it is common to incorporate words of different languages into your native language, thus mock language.

Hill analyzes the 'inner sphere' and 'outer spheres' in which Puerto Ricans living in New York uses their bilingualism. In the inner sphere of neighborhood and intimates such as family and close friends, the boundaries between English and Spanish are blurred formally and functionally. However, in the outer sphere with strangers or government officials, the usage of Spanish becomes marked and "sharply objectified" to the point where the boundaries are so distinct that bilingual speakers may become too scared to speak at all.[3] This shows the hegemonic power of English and how Spanish speakers feel vulnerable and powerless to use Spanish. The need for perfect English is absolute, yet when English speakers dabble in Spanish in this mocking way, there is no nervousness, as their agency extends beyond English hegemony and into the power an English speaker holds in American society. Hill also discusses how semantic domains index a state.[3] Saying something is "el cheapo" indexes that Spanish speakers do not have money or commonly buy cheap, crappy goods.

In a more recent study of Mock White Girl, researcher Tyanna Slobe explains how it is a hegemonic representation of a language being dominated than another and how people would to try to identify with that race by saying a combination of words in that language. “...complicating the moralizing gaze with which linguists have approached mock as uniformly reproducing white supremacist ideologies.”[4] This is the performance piece that people want others to portray themselves to why they would speak this way.

Mock white girl shows how the intentional use of vocal fry to convey a mockery of the white, upper-class, suburban, spoiled young adult or teenager is conveying a shared meaning that the language the speaker is mocking is subordinate and not to be taken seriously. It indexes the characteristics of a stereotypical white girl and uses the n+1 level of indexicality for the public to make the connection between the mockery and the speech community.

Another semantic domain is language crossing. “Language crossing involves code alternation by people who are not accepted members of the group associated with the second language that they are using (code switching into varieties that are not generally thought to belong to them). This kind of switching involves a distinct sense of movement across social or ethnic boundaries and it raises issues of legitimacy which, in one way or another, participants need to negotiate in the course of their encounter.”[5] This is similar to mock language as the people code alternating are not members of the group, similar to how mock-language speakers are English speakers not members of the language they are mocking.

Implications of Study

Mock language is used in anthropology and linguistics to interpret different languages in a conversation and the characteristics of borrowing words from a language. It is important to study mock language in order to preserve the original foundations of languages or dialects that have become subject to the pressure of globalization. Each time a mock phrase is used, it reinforces the divergence from the original language. Globalization occurs at a much faster rate today than in the past, largely due to technological advancements that connect the world with no regard for national borders. American culture is overwhelmingly dominant in the field of online media, and American interpretations of other cultures often become somewhat of a universal standard, at least in terms of exposure. This makes it important for linguists to analyze such interpretations and recognize their origins.

The study of Mock Language also reveals several powerful racial ideologies in the way English speakers hold agency to use other languages carelessly. “It is certainly useful to think of linguistic signs as being bound to historical contexts. But a limited historical view of language fails to address the fact that speakers are often not aware of the historical references they make by using particular signs.”[6] This leads to a general ignorance, mostly from the perspective of English speakers, regarding the use of certain phrases. Misuses of certain words can eventually be attributed to legitimate cultures after overuse, especially with the help of modern media as a medium of exposure, undermining history and often introducing the possibility of offending native speakers.

Controversy

In the United States, the dominant language ideology is that English should be the official language.[7] There are many social, economic, environmental disadvantages of minority groups. The dominant ideology does not allow these groups to celebrate their language, yet “mock language involves borrowings and wordplay by speakers who require little comprehension of the other language.”[8] Mock language reinforces the status and social differences of native English speakers versus minorities and ethnic communities.

Features of Mock Language

While not every use of mock language is the same, aspects such as gendered indicators, greetings, and pronouns are commonly used. It may come about without the intention of knowing the harm for that language's speech community. Mock Spanish commonly uses gendered pronouns of 'el', 'la', and adds '-o' to the end of words.

Mock-white girl is a type of mock language that is inspired by the stereotypical "white girl's" vernacular. It commonly uses features such as 'like' in excess to imply the speaker is not well spoken or articulate. It also features uptalk, creaky voice, blondness and the stereotypical association with Starbucks.[4]

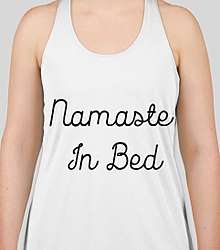

Mock-Hindi has taken the word 'namaste' out of context singularly and does not borrow other words or linguistic features from the language. While these are all very different mock languages features, they all do not respect the original languages and highlight the language ideology of English dominance in the US. Additionally, it does not code switch between the two languages, a linguistic term for switching between two languages the speaker knows, as the speaker clearly does not know Hindi when using it in such a context.

Mock Spanish

It has been adapted in society for people to code switch between languages but there is a boundary where "speaking" the language is inauthentic and distasteful. People tend to say "el" or add an "o" at the end of words as if they are speaking mock Spanish such as el cheapo, no problemo. The semantic domain is cheapness and it suggests that Spanish speakers have a limited amount of money and like to get things that are lower quality and low-priced.

“Mock Spanish relies upon the semiotic construction of two basic social types: the easygoing, humorous, and somewhat cosmopolitan white person and the lazy, dirty, sexually “loose,” and unintelligent Spanish speaker.”[9]

Examples

Popular T-shirts for young women with the saying "namaste in bed". This borrows the traditional greeting from Hindi and makes it into a pun of the slang term "imma stay in bed". It also associates the Hindi word as a yoga term, though this is misappropriation as it is a term used for greeting, not concluding a yoga session. It is in relation to being lazy.

Cinco de Mayo, a holiday that celebrates Mexico’s defeat of the French on May 5, 1862, has become extremely popular in the United States as a celebration based largely on the consumption of alcohol. Due to this association, the term “Cinco de Drinko” has emerged, representing both ignorance toward the holiday’s history and an example of the “add ‘o’” phenomenon. The “add ‘o’” phenomenon is the practice of English speakers adding an “o” to the end of an English word in order to give it the false appeal of being a Spanish word.

"Mock White Girl" is a common example that is seen in movies where the girls are speaking in standard English with creaky voice and are trying to be portrayed as privileged, popular, and in power. In the 2004 film Mean Girls, character Regina George is known to be the most popular girl in school and throughout the movie she has the voice for people to recognize her status.[10]

Bars and pubs around the world have signs that try to imitate European bar and pub culture. Oftentimes, German is incorporated due to the association of German culture with drinking. This decontextualization and use of stereotype is mock language. Danke is German for "thank you", but it is decontextualized in an English-speaking environment.

The signs are using German as an international language of beer or drinking, but "das boot" in German translates as “the boat” and has nothing to do with shoes or drinking. Nevertheless, it is used as the name of a drink represented by footwear. Using 'danke' in a pub may show knowledge of a direct translation, however it stereotypes drinking beer with German culture and language.

References

- Hill, Jane H. "Mock Spanish: A Site For The Indexical Reproduction Of Racism In American English". language-culture.binghamton.edu. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- Lull, James (2000). Media, Communication, Culture: A Global Approach. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231120739.

- Hill, Jane (1998). "Language, Race, and White Public Space". American Anthropologist. 100 (3): 680–689. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.680. JSTOR 682046.

- Slobe, Tyanna (2018). "Style, Stance, and Social Meaning in Mock White Girl". Language in Society.

- Rampton, Ben (1995-12-01). "Language crossing and the problematisation of ethnicity and socialisation". Pragmatics. 5 (4): 485–513. doi:10.1075/prag.5.4.04ram. ISSN 1018-2101.

- Chun, Elaine W. (June 2001). "The Construction of White, Black, and Korean American Identities through African American Vernacular English". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 11 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1525/jlin.2001.11.1.52. ISSN 1055-1360.

- "Americans Strongly Favor English as Official Language". Rasmussen Reports. 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- Vessey, Rachelle (2014). "Borrowed words, mock language and nationalism in Canada". Language and Intercultural Communication. 14 (2): 176–190. doi:10.1080/14708477.2013.863905. eISSN 1747-759X. ISSN 1470-8477.

- Roth-Gordon, Jennifer (2011-11-24). "Discipline and Disorder in the Whiteness of Mock Spanish". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 21 (2): 211–229. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1395.2011.01107.x. ISSN 1055-1360.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAOmTMCtGkI