Miran (Xinjiang)

Miran is an ancient oasis town located on the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, Northwest China. Located where the Lop Nur desert meets the Altun Shan mountains, Miran was once a stop on the famous trade route known as the Silk Road. Two thousand years ago a river flowed down from the mountain and Miran had a sophisticated irrigation system. Now the area is a sparsely inhabited, dusty region with poor roads and minimal transportation.[1] Archaeological excavations since the early 20th century have uncovered an extensive Buddhist monastic site that existed between the 2nd to 5th centuries AD, as well as the Miran fort, a Tibetan settlement during the 8th and 9th centuries AD.

Stupa at Miran | |

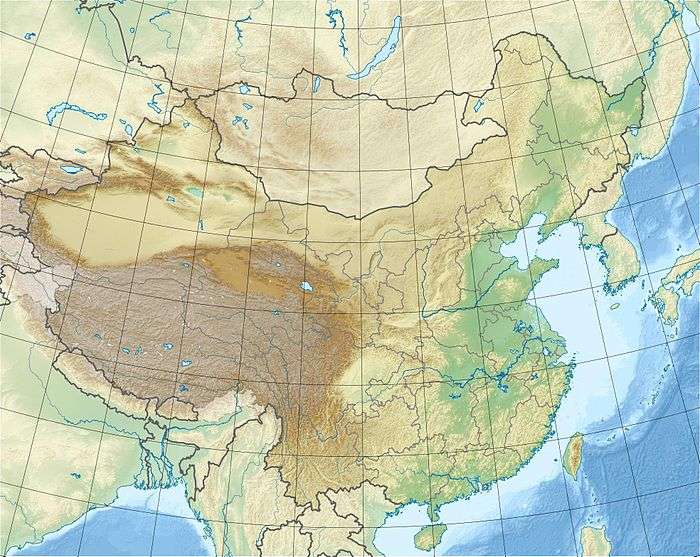

Location of Miran in China | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Region | Xinjiang |

| Coordinates | |

Names

Lionel Giles has recorded the following names for Miran (with his Wade-Giles forms of the Chinese names converted to pinyin):

- "Yuni, old capital of Loulan [Former Han]

- "Old Eastern Town" ; "Little Shanshan" [Later Han]

- Qitun Cheng ; Tun Cheng [Tang]

- Mirān [modern name].[2]

During the period of Tibetan occupation (mid-8th to mid-9th centuries), the area was known as Nop Chungu (nob chu ngu).[3]

History

_(14782860032).jpg)

In ancient times, Miran was a busy trading center on the southern part of the Silk Road, after the route split into two (the northern route and the southern route), as caravans of merchants sought to escape travel across the harsh wasteland of the desert (called by the Chinese "The Sea of Death") and the Tarim Basin. They went by going around its north or south rim. It was also a thriving center of Buddhism with many monasteries and stupas.[1][4][5] Buddhist devotees would have walked around the covered circular stupas, whose central pillar contained relics of the Buddha.[6]

Miran was one of the smaller towns in Kroraina (also known as Loulan), which was brought under the control of the Chinese Han Dynasty in the third century.[1][4] After the fourth century the trading center declined. In the mid eighth century, Miran became a fort town because of its location at the mouth of a pass on one of the routes into Tibet. This is where the Tibetan forces crossed when the Chinese army withdrew to deal with rebels in central China. The Tibetans remained there, using the old irrigation system, until the Tibetan Empire lost its territories in Central Asia around the middle of the ninth century.[1]

Archaeology

.jpg)

The ruins at Miran consist of a large rectangular fort, a monastery ('the Vihara' in Stein's accounts), several stupas and many sun-dried brick constructions, located relatively close to the ancient caravan track to Dunhuang, running west to east. The many artifacts found in Miran demonstrate the extensive and sophisticated trade connections these ancient towns had with places as far away as the Mediterranean Sea. Archaeological evidence from Miran shows the influence of Buddhism on artistic work as early as the first century BC.[7] Early Buddhist sculptures and murals excavated from the site show stylistic similarities to the traditions of Central Asia and North India[8] and other artistic aspects of the paintings found there suggest that Miran had a direct connection with Rome and its provinces.[9] This Romanesque style is thought to be the work of a Buddhist painter known as Tita (Titus), who was perhaps a Roman artist who traveled east along the Silk Roads in search of employment.[10] Several artefacts have been found at the Miran site, including bows and arrows.[11]

Expeditions and visitors to the site

- 1876: The first person to mention the ancient site was Nikolay Przhevalsky. After his second expedition to the region, he wrote about a very large ruined city near the Lopnor lake, which, judging from its geographical position on his map, must have been Miran.[12]

- 1905: Ellsworth Huntington, an American geologist, the first to examine Miran, identified the fort, the monastery, and two stupas during a short visit, and recognized the Buddhist character of the site.

- 1906-1907: Aurel Stein visited and excavated Miran fort and surrounding sites during his second expedition to Central Asia, carrying out a thorough excavation of the fort, uncovering 44 rooms (site numbers M.I.i - M.I.xliv). He excavated other sites in the area, mainly to the north and west of the fort (site numbers M.II - M.X), including several temples containing well-preserved Buddhist fresco and stucco images.[13]

- 1902 and 1910: Count Ōtani Kōzui sent missions from Kyoto to some Taklamakan sites, among them Miran, to bring back Buddhist texts, wall paintings and sculptures.[14]

- 1914: Aurel Stein returned to Miran on his third expedition, excavating other sites in the area (site numbers M.XI - M.XV), which were ruins of stupas and towers. The objects found in these included more stucco images and wooden carved objects.[15]

- 1957-8: Professor Huang Wenbi lead a team from the Institute of Archaeology, CASS, spending six days at Miran, and a report was published in 1983 describing the fort and two stupa/temple sites, and a number of finds.

- 1959: A team from Xinjiang Museum spent ten days in Miran examining the fort, temple site and dwelling areas. A report of their considerable findings was published in 1960.

- 1965: Rao Reifu, an engineer, investigated the remains of a substantial irrigation system in the Miran area and published his findings in 1982.

- 1973: Another team from the Xinjiang Museum visited the site an investigated the fort, temples and irrigation system. The excavations and the artefacts found in these sites were discussed in an expedition report by Mu Shunying in 1983.

- 1978-80: The most extensive investigation of the site so far was carried out by Huang Xiaojing and Zhang Ping of the Xinjiang Museum. Their 1985 report discusses the fort, 8 stupas, 3 temple sites, 2 beacons, dwellings, tombs, a kiln area and a smelting site.

- 1988: The archaeological team of XJASS visited the site and published a report, containing little new information.

- 1989: Professor Wang Binghua visited several of the temple sites.

- 1989: Christa Paula visited Miran, and published a description with photographs.[16]

- 1996: Peter Yung visited Miran recording his experiences in words and photographs.[17]

See also

- Shanshan

- Lop Nur

- Xiaohe Tomb complex

- Niya

- Loulan Kingdom

- Charklik

Footnotes

- The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- Giles (1930-1932), p. 845.

- Thomas, F.W. (1951). Tibetan Literary Texts and Documents, Volume II. London: Royal Asiatic Society. pp119–166.

- "Southern Silk Road". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- Hill (2009), pp. 89-90, 93, 98, 137, 269.

- Hansen, Valerie (2012). The Silk Road, A New History. Oxford.

- Henri Albert van Oort (1986). The Iconography of Chinese Buddhism in Traditional China. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- "Silk Road Trade Routes". University of Washington. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- "Ten Centuries of Art on the Silk Road". Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- Richard Foltz (2000). Religion of the Silk Road. Basingstoke.

- Hall, Andrew (2008). Bows and Arrows from Miran, China. The Society of Archer-Antiquaries, #51. pp. 89–98.

- Przhevalsky, Nikolai Mikhailovich (1879). From Kulja, across the Tian Shan to Lob-Nor. London: Sampson Low.

- Stein, Mark Aurel (1921). Serindia. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Sugiyama, Jiro (1971). Central Asian Objects brought back by the Otani Mission. Tokyo National Museum.

- Stein, Marc Aurel (1928). Innermost Asia. Clarendon Press.

- Paul, Christa (1994). The Road to Miran: Travels in the Forbidden Zone of Xinjiang. London: HarperCollins.

- Yung, Peter (1997). Bazaars of Chineses Turkestan: Life and Trade Along the Old Silk Road. Hong Kong, Oxford University Press.

References

- Giles, Lionel (1930-1932). "A Chinese Geographical Text of the Ninth Century." BSOS VI, pp. 825–846.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

External links

- Along the ancient silk routes: Central Asian art from the West Berlin State Museums, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material from Miran

- Some Aspects Of Jataka Paintings in Indian and Chinese (Central Asian) Art

- Mīrān Fort - Placename Information on the Digital Silk Road website