Milt Gabler

Milton Gabler (May 20, 1911 – July 20, 2001)[1] was an American record producer, responsible for many innovations in the recording industry of the 20th century.

Milt Gabler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Milton Gabler May 20, 1911 Harlem, New York |

| Died | July 20, 2001 (aged 90) Manhattan, New York |

| Family | Billy Crystal (nephew) |

| Awards | Member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame |

| Musical career | |

| Occupation(s) | Record producer |

| Labels | Commodore Records |

Early life

Gabler was born to a Jewish family[2] in Harlem, New York, the son of Susie (née Kasindorf) and Julius Gabler. His father was an Austrian Jewish immigrant (from Vienna), and his mother's family were Jewish immigrants from Russia (including Rostov).[3][4] At 15, he began working in his father's business, the Commodore Radio Corporation, a radio shop located on East 42nd Street in New York City.

1930s

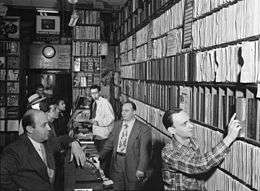

By the mid-1930s, Gabler renamed the business the Commodore Music Shop, and it became a focal point for jazz fans and musicians alike. In 1933 Gabler began buying up unwanted copies of recordings from the record companies and resold them, making him the first person to deal in reissues, the first to sell records by mail order, and also the first to credit all the musicians on the recordings.

Gabler started up a specialty label UHCA (United Hot Clubs of America) in about 1935 to reissue selected 78 r.p.m. sides previously released by other companies. He was able to secure many important jazz records including the 1931 Joe Venuti-Eddie Lang all star session (from ARC), Bessie Smith's final session (from OKeh), a number of Frank Trumbauer, Bix Beiderbecke, and Miff Mole sides (also from OKeh). These reissues were from the original 78 stampers and were instrumental in spreading the concept of collecting classic performances from the past. A number of Paramount and Gennett sides were dubbed from clean copies and issued on UHCA and the sound was surprisingly good for a dubbing.

In 1937 he opened a new store on 52nd Street, and set up a series of jam sessions in a neighbouring club, Jimmy Ryan's. Some of these he began recording, setting up his own record label, Commodore Records. His role as a music producer soon superseded his other activities and he recorded many of the leading jazz artists of the day. One regular customer, Billie Holiday, found her record company, Columbia, resisting her appeals to release the song "Strange Fruit", so she offered the song to Gabler. After getting the necessary permission, he released her recording on Commodore in 1939, boosting her career and issuing what, 60 years on, Time magazine named Best Song of the Century.

1940s

The success of Commodore Records inevitably led to an offer to join a major record label. Gabler was recruited to work for Decca Records in 1941, and left his brother-in-law Jack Crystal (father of Billy Crystal) to run Commodore. Gabler was soon working with many of the biggest stars of the 1940s, producing a series of hits including Lionel Hampton’s "Flying Home", Billie Holiday’s "Lover Man" and The Andrews Sisters' "Rum and Coca-Cola", as well as being the first to bring Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald together on record.

Put in charge of Decca’s subsidiary label Coral, he expanded his musical scope, producing hits for country singer Red Foley, the left-leaning folk group The Weavers, Peggy Lee, The Ink Spots, and Sammy Davis Jr. In 1946 he produced and co-wrote Louis Jordan’s breakthrough single, "Choo Choo Ch'Boogie", a foretaste of the musical revolution around the corner.

1950s and 1960s

Gabler contributed a further slice of history when he signed Bill Haley and His Comets to Decca Records. He produced their initial recording session in April 1954,[6] much of which was spent cutting a song which the company thought the more likely hit of the two due to be recorded that day. Their efforts on "13 Women" left only ten minutes for the second song, which Gabler recorded with an unusually high sound level after the briefest of sound checks. "Rock Around The Clock" was cut in two takes and changed the face of popular music. Gabler later commented : "All the tricks I used with Louis Jordan, I used with Bill Haley.[7][8] The only difference was the way we did the rhythm. On Jordan, we used a perfectly balanced rhythm section from the swing era ... but Bill had the heavy backbeat."

Commodore Records was wound up in 1954. Bob Shad's Mainstream Records issued a series of albums of Commodore material in the early 1960s, keeping most of these recordings available. However, through the late 1950s and 1960s, Gabler continued to guide the direction of Decca, writing songs and producing hit singles including Brenda Lee’s “I’m Sorry” and albums including Jesus Christ Superstar. Gabler also continued to produce all of the Comets' recordings for Decca until they left the label in 1959.

Milt Gabler also produced all studio-albums in Hamburg for Bert Kaempfert and his Orchestra from 1960 to the latter's death in June 1980. He wrote many lyrics for Kaempfert songs, like "L-O-V-E", a very big hit for Nat King Cole, and "Danke Schoen".

Later years

He retired from the front line of business activity when MCA consolidated Decca with its other labels and moved the merged MCA Records to Universal City, California in 1971, but continued to produce reissues and to collect recognition from the recording industry he helped shape. He was asked to return to MCA Records in 1973 to supervise the reissue of MCA's massive back catalogue.[9]

Gabler died July 20, 2001, aged 90, at the Jewish Home and Hospital in Manhattan. The New York Times reported that the only photo at his bedside was that of Billie Holiday.[10]

Accolades

In 1991, Gabler received the Grammy Trustees Award from The Recording Academy, for his significant contributions to the field of recording.[11]

In 1993, Gabler was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by his nephew, the comedian and actor Billy Crystal. In 2005, Crystal produced a documentary and CD release, both entitled The Milt Gabler Story, in tribute.[12]

References

- Levin, Floyd (2002). "Gabler, Milt(on)". In Barry Kernfeld (ed.). The new Grove dictionary of jazz (2nd ed.). New York: Grove's Dictionaries Inc. p. 1. ISBN 1-56159-284-6.

- Cherry, Robert; Griffith, Jennifer (Summer 2014). "Down to Business: Herman Lubinsky and the Postwar Music Industry". Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1-24.

- Crystal, Billy (October 2005). 700 Sundays. p. 23. ISBN 0-446-57867-3.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-23. Retrieved 2013-10-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- McNally, Owen (March 30, 2000). "'Song of the century' chilling: Graphic lyrics of 'the first unmuted cry against racism' are making a comeback". Ottawa Citizen.

- Hoffmann, Frank, Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound, 2nd ed., New York, NY : Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-93835-X. Cf. volume 1 (of two), pp.421-422, article on "Milt Gabler".

- "5 Candidates for the First Rock 'n' Roll Song". Mentalfloss. March 23, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- https://wwwrock'n'roll.theguardian.com/music/2004/apr/16/popandrock#:~:text=The%20most%20widely%20held%20belief,records%20and%20discover%20Elvis%20Presley. Will the creator of modern music please stand up?]

- Billboard - Google Books

- Martin, Douglas (July 25, 2001). "Milton Gabler, Storekeeper of the Jazz World, Dies at 90". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-07-24.

- "Trustees Award". The Recording Academy. Archived from the original on 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2016-07-24.

- "Milt Gabler". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2016-07-24.

Further reading

- Koester, Bob, "Milt Gabler & Commodore Records", Rhythm & News, Delmark Records

External links

- From Ashley Kahn's liner notes to Billy Crystal Presents: The Milt Gabler Story. - "Billy Crystal: My Uncle Milt"

- "Profile: Milt Gabler" - Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

- "Biography: Milt Gabler", Allmusic

- Milt Gabler music, papers, and audio recordings collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University.