Fujiwara no Michinaga

Fujiwara no Michinaga (藤原 道長, 966 – January 3, 1028) was a Japanese statesman. The Fujiwara clan's control over Japan and its politics reached its zenith under his leadership.

Fujiwara no Michinaga | |

|---|---|

Fujiwara no Michinaga — drawing Kikuchi Yōsai (1781-1878) | |

| Daijō-daijin | |

| In office 24 December 1017 – 27 February 1018 | |

| Monarch | Emperor Go-Ichijō |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 966 |

| Died | 3 January 1028 (aged 62) |

| Relations | Fujiwara no Michitaka (brother) Fujiwara no Korechika (nephew) Fujiwara no Teishi (niece) Princess Teishi (granddaughter) Emperor Ichijō (1st son-in-law) Emperor Sanjō (2nd son-in-law) Emperor Go-Ichijō (4th son-in-law) Emperor Go-Suzaku (6th son-in-law) |

| Children | Empress Shōshi (1st daughter) Fujiwara no Yorimichi (1st son) Fujiwara no Kenshi (2nd daughter) Fujiwara no Norimichi (5th son) Fujiwara no Ishi (4th daughter) Fujiwara no Kishi (6th daughter) |

| Parents | Fujiwara no Kaneie |

Early Life

Michinaga was born in Kyōto, the son of Kaneiye. Kaneiye had become Regent in 986, holding the position until the end of his life in 990. Due to the hereditary principle of the Fujiwara Regents, Michinaga was now in line to become Regent after his brothers, Michitaka and Michikane.

Career

Struggle with Korechika

Michitaka was regent from 990 until 995, when he died. Michikane then succeeded him, famously ruling as Regent for only seven days, before he too died of disease. With his two elder brothers dead, Michinaga then struggled with Fujiwara no Korechika, Michitaka's eldest son and the successor he had named. Korechika was more popular at court than Michinaga, being a favourite of Empress Teishi and well-liked by the reigning Emperor Ichijō, and held multiple prestigious positions - he had been made Naidaijin the previous year, and Sangi three years before that. However, the mother of Ichijo, Fujiwara no Senshi, disliked Korechika and aided Michinaga; for example, she coerced Ichijo into granting Michinaga the title of Nairan (内覧) in the fifth month of 995. Furthermore, Korechika's position was ruined by a scandal that took place the following year, likely arranged by Michinaga.

Korechika had been seeing a mistress in one of the Fujiwara palaces. However, he was told that the retired Emperor Kazan had been visiting the same house during the night - Korechika presumed that Kazan had been seeing the same mistress. Consequently, he and his brother Takaiye ambushed the Emperor, shooting at him. An arrow struck Kazan's sleeve, a grave crime - it was considered appalling to harm a monk (for Kazan had entered religion in 986), let alone an Emperor. Michinaga and his supporters then pressed charges of lèse-majesté. Though the jurists examining the case found the servants of Kaneiye and Takaiye at fault, further charges were manufactured by Michinaga's faction: Korechika was accused of putting a curse on Senshi, for example. Their punishments were a form of cordial banishments, with Korechika made Vice-Governor of Kyushu. With Korechika removed from the capital, Michinaga had won their struggle for supremacy.

During their struggle, Michinaga had gained the position of Minister of the Right, or Udaijin (右大臣), on the 19th day of the 6th month of 995. Later in 996 Michinaga became Minister of the Left, Sadaijin (左大臣), the most senior position in government apart from that of Chancellor (Daijō-daijin).[1]

Rule as Mido Kampaku

During his lifetime, Michinaga was called the Mido Kampaku, a title referencing the name of his residence, Mido, and the fact that he was Regent in all but name.[2]

The primary method through which the Fujiwara regents maintained their power was through controlling the sovereign, usually through matrimonial links. Michinaga was particularly successful in this regard, with four of his daughters marrying an emperor. Although Ichijo already had an Empress, Teishi, Michinaga made her Kogo empress and had his first daughter, Shoshi, also marry him as Chūgū empress. This was the first time that an emperor had two empresses consort simultaneously. Chūgū was the more senior of the two ranks, at least unofficially. When Teishi died in childbirth in 1001, Michinaga's influence over Ichijo was absolute.

Kenshi, Michinaga's second daughter, married the future Emperor Sanjō. Ichijo and Shoshi had two sons, both future emperors, and it was to these that Michinaga's third and fourth daughters were married: Ichijo's eldest son, Go-Ichijō, married the third daughter, Ishi; and Ichijo's second son, Go-Suzaku, married the fourth daughter, Kishi.

Michinaga further cemented his power by making alliances with the powerful warrior clans, particularly the Minamoto (or more specifically the Seiwa Genji), as demonstrated by the fact that both of his wives were Minamoto. Minamoto no Yorimitsu and Minamoto no Yorinobu were his two principal commanders: they were loyal and effective to the extent that their enemies called them the Fujiwara's 'running dogs'. The support of these powerful warriors meant that Michinaga could threaten his enemies with violence, something that they were unable to respond to - even the imperial clan would've been unsafe if Michinaga wished to attack them, given the ornamental nature of their Guard.

It is clear that Michinaga controlled or influenced all important imperial figures of his time. It was for this reason that Michinaga never formally took the title of Kampaku - he already possessed the power that the title carried. The supremacy of Michinaga during his lifetime is demonstrated by the fact that in 1011 he was granted the exceptional privilege of travelling to and from the court by ox-drawn cart.[3] In the same year, Ichijo's second son, Atsunari, was proclaimed Crown Prince. Sanjō's eldest son, Atsuakira, had been the previous heir, but Michinaga leveraged his powerful position to make the Crown Prince resign. In order to prevent Atsuakira from being an enemy to him, Michinaga married his fifth daughter, Kanshi, to him.

During Sanjō's reign as Emperor, he and Michinaga often came into conflict. Resultantly, Michinaga attempted to pressure Sanjō into retirement. In 1016 he was finally successful. The youth of Go-Ichijō meant that Michinaga ruled as Sesshō, the Regency assumed when the emperor is yet to come of age. He briefly became Chancellor in the final month of 1017, before resigning in the second month of the following year. A month after his resignation, he also resigned from the position of Sesshō in favour of Yorimichi, his eldest son. In 1019 he took the tonsure, becoming a monk at the Hōjō-ji, which he had built. He took the Dharma name Gyōkan (行観), which was later changed to Gyōkaku (行覚).

Death and Legacy

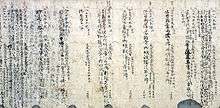

On January 3rd 1028, Michinaga died at the age of sixty-two. He is said to have called out to Amida on his deathbed, asking for entry to Paradise. He left a diary, the Midō Kanpakuki; it is an important source of information about the Heian court at the height of Fujiwara power, though somewhat overshadowed by Murasaki's Tale of Genji and Sei's Pillow Book. In the Tale of Genji, the eponymous Genji is believed to be in part based on Michinaga, as well as Korechika.

Personality

Michinaga was reputed to be a skilled horseman and archer, and was perceived as courageous. His friends praised his poetry and he was reputed to have strong self-control. He clearly had a remarkable understanding of people and the human heart, given the success of his machinations - the Fujiwara were strongest under his control, despite a broader trend of the power of the sovereigns weakening and that of the provincial warrior clans growing.

He had a taste for opulence and luxury, holding extravagant parties and entertainments, though it was nonetheless governed by the tasteful modesty that characterises the Heian period. His extravagance had a purpose, however - it openly demonstrated the wealth and power of the Fujiwara clan, impressing allies and intimidating rivals.

Michinaga may have been pious, given his vast expenditure on shrines and temples, though this may have been another manifestation of the aforementioned excess. On the other hand, he was known to sternly rebuke courtiers who neglected Shinto ceremonies. He was a devoted follower of the Lotus Sutra; his copy had the words embellished in gold. When Amidist Pure Land Buddhism began to grow and develop during his rule, Michinaga supported and adopted its teachings.

Michinaga was very proud of his achievements, as demonstrated by his poem, Mochizuki no Uta (望月の歌) (Full Moon Poem), which he composed in 1018 at a party to celebrate Ishi becoming Chūgū to Go-Ichijō: "This world, I think/ Is indeed my world./ Like the full moon I shine,/ Uncovered by any cloud"

Genealogy

He was married to Minamoto no Rinshi, otherwise known as Michiko (源倫子), daughter of Sadaijin Minamoto no Masanobu. They had six children.

- Shōshi (彰子) (Jōtōmon-in, 上東門院) (988–1074) – consort of Emperor Ichijō.

- Yorimichi (頼通) (992–1074) – regent for Emperor Go-Ichijō, Emperor Go-Suzaku, and Emperor Go-Reizei.

- Kenshi (妍子) (994–1027) – consort of Emperor Sanjō.

- Norimichi (教通) (996–1075) – regent for Emperor Go-Sanjō and Emperor Shirakawa.

- Ishi (威子) (999–1036) – consort of Emperor Go-Ichijō.

- Kishi (嬉子) (1007–1025) – consort of Crown Prince Atsunaga (later Emperor Go-Suzaku).

He was also married to Minamoto no Meishi (源明子), daughter of Sadaijin Minamoto no Takaakira. They had six children.

- Yorimune (頼宗) (993–1065) – Udaijin.

- Akinobu (顕信) (994–1027) – He became a priest at the age of 19.

- Yoshinobu (能信) (995–1065) – Gon-no-Dainagon.

- Kanshi (寛子) (999–1025) – consort of Imperial Prince Atsuakira (Ko-Ichijō-in).

- Takako (尊子) (1003?–1087?) – married to Minamoto no Morofusa.

- Nagaie (長家) (1005–1064) – Gon-no-Dainagon.

Michinaga had one daughter from an unknown woman.

- Seishi (盛子) (?–?) – married to Emperor Sanjō

Bibliography

- Brown, Delmer M. and Ichirō Ishida, eds. (1979). Gukanshō: The Future and the Past. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03460-0; OCLC 251325323

- Hioki, S. (1990). Nihon Keifu Sōran. Kodansya. (in Japanese)

- Kasai, M. (1991). Kugyō Bunin Nenpyō. Yamakawa Shuppan-sha. (in Japanese)

- Owada, T. et al. (2003). Nihonshi Shoka Keizu Jimmei Jiten. Kodansya. (in Japanese)

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard Arthur Brabazon. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan. Kyoto: Ponsonby Memorial Society. OCLC 194887

- Titsingh, Isaac. (1834). Nihon Odai Ichiran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Royal Asiatic Society, Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. OCLC 5850691

- Tsuchida, N. (1973). Nihon no Rekishi No.5. Chūō Kōron Sha.

- Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki: A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-04940-5; OCLC 59145842

- Sansom, George (1958). A History of Japan to 1334. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804705233.

References

- Brown, Delmer et al. (1979). Gukanshō, p. 304.

- Frédéric, Louis (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780674017535. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Brown, p. 307.