Michael Grigsby

Michael Kenneth Christian Grigsby (7 June 1936 – 12 March 2013) was an English documentary filmmaker.[1]

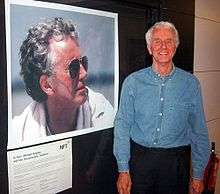

Michael Grisgby | |

|---|---|

Michael Grigsby c.1955 | |

| Born | 7 June 1936 |

| Died | 12 March 2013 (aged 76) |

With a filmography spanning six decades and nearly 30 films, Grigsby occupies a unique position in British documentary filmmaking, having witnessed and commented on many of the dramatic changes in British society (and beyond) from the late 1950s into the next century. As a critic noted, "from Michael Grigsby back to John Grierson runs an unbroken tradition in British documentary-making: a passionate commitment to the poetry of everyday life."[2]

Early life and career

Born in Reading, Berkshire, Grigsby’s passion for documentary dates back to his time at Abingdon School, an independent boarding school for boys, where he attended from 1949 through 1955.[3] There, he ran the school’s film society and discovered the films of John Grierson’s documentary movement. These had an amazing impact on then 14-year-old boy. While at school, he also talked the headmaster into funding his first attempts at documentary filmmaking. He produced Ut Proficias in 1953, which was placed with the British Film Institute.[4] [5] Another film, No Tumbled House (1955), deals with the realities faced by a boy in a boarding school.

Career

After leaving Abingdon, he gained his first job as a trainee assistant editor at Granada Television in Manchester, working with Harry Watt, who had co-directed the short film Night Mail (1936). Unfortunately, Watt left shortly afterwards, and Grigsby was then offered a job as a studio cameraman, which by his own admission was very dull, but gave him a chance to purchase his own 16mm Bolex camera.

Along with a bunch of disaffected Granada colleagues, he set up a filmmaking collective, Unit Five Seven, and spent several years shooting and editing Enginemen, a short film about work in a locomotive shed, in his spare time.[6] By chance, the critic and filmmaker Lindsay Anderson heard of his project. Anderson was particularly impressed by the rushes, and with fellow filmmaker Karel Reisz, he helped Grigsby secure funding from the British Film Institute to complete the film, which was included in the last Free Cinema programme at the National Film Theatre in March 1959, alongside Reisz’s We Are the Lambeth Boys and Robert Vas’ Refuge England. Growing in confidence, Grigsby made another short documentary with the Unit Five Seven, Tomorrow’s Saturday (1962), about mill workers in Blackburn, Lancashire preparing for the weekend. After these two well received shorts, he succeeded in persuading Granada to support his work and was finally allowed to direct his first documentary for the company, Deckie Learner (1965).[7]

Later work

His work continued to demonstrate a fidelity to the concerns and principles embodied in these early films. Grigsby set out to make films about ordinary people, and those at society’s margin. He gained a reputation as a filmmaker who – to use his own words – "gives a voice to the voiceless". Thus, whether he’s filming trawlermen (Deckie Learner, 1965; A Life Apart, 1973), the survivors on both sides of the Vietnam War (I Was a Soldier, 1970; The Search, 1991; Thoi Noi, 1993), ordinary inhabitants of Northern Ireland (Too Long a Sacrifice, 1984; The Silent War, 1990; Rehearsals, 2005), families facing up to social disintegration in Thatcher’s Britain (Living on the Edge, 1987) or the traumatised Lockerbie community 10 years after the Boeing 747 disaster (Lockerbie, A Night Remembered, 1998), Grigsby does his utmost to let people speak for themselves. Hence his belief in the importance of long research periods (up to six months) prior to shooting, to gain the participants’ trust; hence also the still frames, the long meditative shots and the moments of silence, allowing people the space in which to get their points across. This unhurried pacing appears truly daring when compared to the frenetic filmic vocabulary more favoured today.

Grigsby’s documentaries have also been compared to free-form jazz; he liked working instinctively, and the structure of his films generally came to him only after he had built a real understanding of the place, the landscape and the people. His films’ inner quality also comes from the highly creative way in which he arranged sounds (often a combination of natural sounds, snatches of dialogues, archive material and live or added music) and images, thus creating symbolic contrasts between them, rather than resorting to a didactic voice-over commentary. In short, Grigsby used eminently cinematic techniques more frequently associated with art cinema than with documentary television. Although he addressed political issues (Northern Ireland, labour relations, effects of wars), there is no crude attempt in his films to ‘propagandise’. Instead, he utilises the documentary genre in a unique fashion, bringing his humanist vision to bear on problems in society, so that viewers become participants too - involved, engaged and thinking.

Influenced by John Grierson’s documentary movement, emerging as part of Free Cinema, his approach reaching maturity during documentary television’s golden age, Grigsby at the later stages of his career came full circle. Still as active and enthusiastic as ever despite the current lack of support for independent, imaginative documentaries in British television, amongst a number of new documentary features, he was working to develop his first fiction feature film. He also returned to the place where he made his first film as a pupil, Abingdon School, to set up the AFU Abingdon Film Unit in 2003 with Jeremy Taylor, the school's Head of Drama,[1] where over thirty boys (and girls from the neighbouring school of St Helen and St Katharine), aged 12 to 18, worked together under their supervision along with several other industry professionals to make a handful of short films each year. He was as proud of this new enterprise as of his finest films; he saw it as his own way of passing on the torch of the great British documentary tradition to the next generation of filmmakers. The Abingdon Film Unit itself has gained significant press, owing to films such as Gravel & Stones (2007), a documentary which focuses on the impact of disability on people in Cambodia, a country that, after thirty years of war, has one of the highest rates of disability in the developing world; and also One Foot on the Ground (2010): a 24-minute film which follows a young Moldovan basketball-player, Andreii Zelenetchii, as he struggles to keep alive his dream of playing professional in Europe’s poorest country.

The Unit has now produced over 150 films, many of which have been screened at festivals throughout the UK and abroad, with a number winning awards along the way. Festivals include Raindance, the London International Documentary Festival and the British Film Festival in Dinard, France. Awards include Best Documentary and Best Animation at the Future Film Festival in London and the National Young Filmmaker’s Award at the Leeds Student Film Festival.

In 2012 Grigsby's non fiction feature, 'We Went to War' was released. Co-authored with creative producer Rebekah Tolley, the film is a follow up to Grigsby's film, I Was a Soldier (1970), and returns to the stories of the three Vietnam veterans of the earlier film: David, Dennis and Lamar, forty years after their return from combat to their homes in the heartlands of Texas.

References

- Ian Christie (21 March 2013). "Michael Grigsby obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- Matthew Sweet "Michael Grigsby: Shooting on the Edge", The Independent, 22 June 2004

- "Valete et Salvete" (PDF). The Abingdonian.

- "Object 55: Ut Proficias". Abingdon School.

- "Ut Proficias". British Film Institute.

- "OA Notes" (PDF). The Abingdonian.

- "Obituary". The Guardian.

External links

Selective filmography

1953: Ut Proficias

1955: No Tumbled House

1959: Enginemen

1962: Tomorrow’s Saturday

1965: Deckie Learner

1965: Pommies

1967: Death by Misadventure: SS Lusitania

1969: If the Village Dies

1969: Deep South

1969: Stones in the Park (one of 5 directors)

1970: I Was A Soldier

1971: Freshman

1972: Working the Land

1973: A Life Apart: Anxieties in a Trawling Community

1974: A life Underground

1976: Bag of Yeast

1976: The People’s Land

1979: Before the Monsoon - Roots of Violence

1979: Before the Monsoon - State of Emergency

1979: Before the Monsoon - Seeds of Democracy

1981: For My Working Life

1984: Too Long a Sacrifice

1987: Living on the Edge

1990: The Silent War

1990: Dear Mr Gorbachev

1991: The Search

1993: Thoi Noi

1994: The Time of Our Lives

1994: Pictures on The Piano

1995: Hidden Voices

1996: Living with the Enemy

1998: Lockerbie, A night Remembered

1998: The Score

1999: Billion Dollar Secret

2001: Solway Harvester – Lost at Sea

2005: Rehearsals

2012: We Went to War