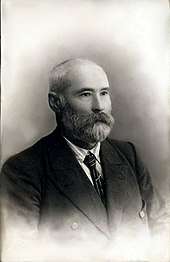

Michał Jankowski

Michał Jankowski or Mikhail Ivanovich Yankovsky (September 24, 1842 – October 10, 1912) was a Polish szlachta nobleman who settled in the Russian Far East after serving a sentence in Siberia for participating in the January Uprising of 1863. After being released in 1868 he settled in the Russian Far-East in Sidemi, Primorsky Krai, in a region now known as the Yankovsky Peninsula where he established a horse-breeding farm, reared deer for their antlers, established ginseng plantations, and became a well-known hunter and naturalist. He collected specimens of fauna and flora for museums and collectors and many species were named after him including Jankowski's bunting.

Life and work

Jankowski was the son of Jan and Elżbieta of Więckowski, born in Złotoria, and came from the nobility of the Novina clan who claimed descent from the knight Tadeusz Novina who fought in the Crusades. He grew up in Złotoria and Tykocin and then went to study at the agricultural university in Hory-Horki near Mogilev. He took part in the January Uprising of 1863 and was captured by the Russians, and sent to Siberia. The prisoners travelled on foot from Smolensk to Siberia. Near Siwakowa near Czyta, he met the fellow Polish zoologist Benedict Dybowski. His sentence was shortened and ended in 1868 after which he applied and received permission to settle in Badajsk in the Irkutsk region. Here he worked in a gold mine from November 1868. In 1872-74 he helped Benedict Dybowski and Viktor Godlewski and joined them on an expedition, providing the team with a boat and learned to prepare specimens from Dybowksi. They travelled along the Amur River to the mouth of the Ussuri River. From 1874, Jankowski managed a gold mine owned by Captain Fridolf Heck on the island of Askold near Vladivostok and in 1877 he established a meteorological station on the island. He married the widow of a soldier on the island, and in 1876 their son Alexander was born but the mother died. Unable to care for the child, he sought a woman, choosing from among several other brides just by examining a set of photographs. He then visited Olga Kuzniecowa who belonged to a Buryat Kurtuk family and she agreed to the marriage. The couple adopted an orphan boy Andrei Agranat on the island of Askold and then also had their own children Elżbieta (born 1878) and Jerzy (born 1879) (Anglicized as George, and Yuri in Russian). He later purchased 550 hectares on the Sidemi peninsula where the family moved to in 1880. The area is now known as the Yankovsky Peninsula. His children Anna (1884), Jan (1886), Sergei (1888) and Paweł (1890) were born there.[2]

The Sidemi area was a rich wilderness with leopards, tigers and threatened by roving gangs of Honghuzi bandits against whom Jankowski and the other settlers waged war. In one attack, the wife of his neighbour Captain Heck was killed along with several workers while his son was kidnapped. Heck, Jankowski, and a group of his trusted Korean farmhands chased the bandits into the Chinese border and Jankowski eventually shot the chief. Jankowski's hunting exploits and brushes with the Honghuzi transformed him into a legend. The Koreans nicknamed him as "nenuni" or four-eyed for his sharp eyesight, spotting bandits, boars, and beetles.[3][4] Jankowski build a strong house as a defence against future attacks, managed orchards, began ginseng plantations, and maintained herds of sika deer (maintained for their velvet antlers which were much sought after in China and Korea) apart from breeding horses. He collected natural history specimens which he sent to Russian and European museums, earning a good income from them. In 1889 he sponsored part of the museum in Vladivostok, now named after Vladimir Arsenyev, and also contributed specimens to it. His sons Yuri ("George") and Alexander also helped in collecting natural history specimens. Yuri and Alexander were also sent to the United States where Yuri studied horse management on Texan farms. They returned with English thoroughbreds aboard a ship from San Francisco. Alexander took an interest in construction, and led a collecting expedition for Vladimir Leontyevich Komarov. Jankowski's horses, bred for a variety of purposes, were used in the cavalry, won races, and pulled plough-shares. He later built leather factories, began a bookstore, and moved to Vladivostok in 1905. During the Russo-Japanese War, he commanded a defence unit. In 1909 he suffered from severe pneumonia and was treated at Semipałatyn and later at Sochi where he lived until his death in 1912. The estate was managed by Yuri after his death.[4][2]

Family escape to Korea

The remaining Jankowski family lived in the region along with other settler families including that of Captain Fridolf Heck and Julius Ivanovich Briner, grandfather of the American actor Yul Brynner, who owned 50 hectares of land. After the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks moved into the area and their lands were seized by the government. Most of the Jankowski family moved out in 1922 to settle further south in what is now North Korea. Jankowski's daughter Anna studied some medicine in Russia and became a member of the Sisters of Mercy. She, contrary to the family political stance, joined the communist party where she came to be called as Comrade Galya and took part in protests against the Tsar, following which she had to flee back east to Sidemi and then forced to live in exile for a while in Japan. She later returned to Sidemi and with her links to the communist party, was the only member of the family that stayed on after the Bolsheviks moved into the area in 1922.[5]

Moving to Korea, Yuri sold off the horses and many of their possessions in Harbin. The family then purchased some land near Chongjin and built up an estate called Novina (after their clan name but also meaning new place). Yuri (now increasingly better known as George) managed this as farm and as a resort which became very successful, attracting many Russian exiles in Korea and their friends. The family later also ran a second resort called Lukomorie closer to the coast.[6] The brothers continued to breed Sika and reindeer, hunt, and grow ginseng. Yuri became a famous tiger hunter and wrote several books. All the children learned to ride horses and hunt. When the Japanese took over Korea, the family earned a living by supplying fresh meat from the forests and from their farm. When the Soviets invaded northern Korea in 1945, Yuri was arrested by the NKVD and the lands taken away. Yuri was sent to the Gulags where he died in 1956.[7] A biography of George Yankovsky was published as The tiger's claw (1956) by Mary Linley Taylor. Yuri's sister Anna who stayed back in Sidemi committed suicide in 1952 following the death of her husband.[8]

Yuri's son Valery (28 May 1911 - 17 April 2010), became a sharpshooter and writer of note. He was nicknamed "nenuni sonja" (grand-son of four-eyes). While in Korea, the Japanese who knew of his hunting prowess showed him a photograph and offered a 10000 yen bounty for hunting a rebel who lived in the forests. Being sympathetic to the local Koreans, he declined to take it up and many years later he realized that the Japanese target had been none other than Kim Il-sung. Valery was also arrested and sent to the Gulags in 1946 but he survived and was released in 1955 after Stalin's death after which he went to live in Magadan. His wife and son had escaped to southern Korea and then emigrated to Canada. He became a writer and wrote several novels and a biographical account of the family in From the crusades to Gulag and beyond (2007).[4][9][3] Yuri's daughters Victoria and Muza moved to the United States of America and Chile. Victoria, noted for wearing earrings made from tiger claws, published a book of her poems. Yuri's son Arseny (1914–1978) escaped to southern Korea and because he knew Korean, Japanese, Russian and English, he was recruited by the Americans and became a CIA operative who went by the name of Andy Brown. As many of his agents got caught and executed in Korea, he was suspected to be a mole and dismissed.[10]

Legacy

A statue to Michał Jankowski made by O.S. Kulesh was unveiled on September 15, 1991 in the village of Bezverkhovo, Primorsky Krai. Numerous species are named after the Jankowskis including Emberiza jankowksii described by the Polish ornithologist Taczanowski , Cygnus columbianus jankowskyi described by Russian ornithologist Alpheraky, and Pica pica jankowksi described by Boris Stegmann. Jankowski senior sent many of his lepidoptera to Charles Oberthür. Insects carrying the family name include Xanthocosmia jankowksi, Spilosoma jankowksi, Marumba jankowksii, and Carabus jankowksii. There are also plants like Alpinia jankowski. A moth Olene olga is named after his second wife. A large number of insects were also collected by the oldest son Alexander between 1937 and 1940 and many are in the Smithsonian Institution collections. A cranefly Prionolabis yankovskyana was named after him by C.P. Alexander.[11][12]

References

- Taczanowski, L. (1888). "Description d'une nouvelle Espece da Genre Emberiza". Ibis. 5. 6: 317–319.

- Egorchev, Ivan (2017). "Дальневосточная одиссея клана Янковских" (in Russian).

- Clark, Donald N. (1994). "Vanished Exiles: The Prewar Russian Community in Korea". In Suh, Dae Sook (ed.). Korean Studies: New Pacific Currents. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 41–58.

- Nowak, Eugeniusz (2018). Biologists in the Age of Totalitarianism: Personal Reminiscences of Ornithologists and Other Naturalists. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 274–290.

- Кушнарева, Т.К. (2008). Янковские. Владивосток: Издательство ВГУЭС.

- Kane, Daniel C. (2004). "Review of Living Dangerously in Korea: The Western Experience 1900—1950". Korean Studies. 28: 131–134. ISSN 0145-840X. JSTOR 23720186.

- Cheong, Sung Hwa (2011). "식민지 시대 러시아인 양코프스키 일가의 한반도 정착기록" [The Story of the Russian Refugees Yankovsky family of Colonial Korea]. The Journal of Humanities (in Korean). 32 (32): 137–160.

- Кушнарева, Т.К. (2008). Янковские. Владивосток: Издательство ВГУЭС.

- Church in North Korea. Translated from Новый храм Воскресения Христова в благодатной Сев. Корее," Хлеб Небесный, ном. 10, 1937

- Harden, Blaine (2015). The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot: The True Story of the Tyrant Who Created North Korea and the Young Lieutenant Who Stole His Way to Freedom. Pan Macmillan. pp. 204–205.

- Alexander, Charles P. (2009). "Undescribed Species of Crane-Flies from Northern Korea (Diptera, Tipuloidea)". Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London. 95 (4): 227–246. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1945.tb00261.x.

- Podenas, Sigitas; Byun, Hye-Wooh; Kim, Sam-Kyu (2015). "New Dicranoptycha Osten Sacken, 1859 Crane flies (Diptera: Limoniidae) of North and South Korea". Zootaxa. 3925 (2): 257. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3925.2.7. PMID 25781743.