Mianus River Bridge

The Mianus River Bridge is a span that carries Interstate 95 over the Mianus River in the Cos Cob section of Greenwich, Connecticut. It is the second bridge on the site. The original bridge collapsed in 1983, killing three motorists. The replacement span is officially named the Michael L. Morano Bridge, after a state senator Michael L. Morano who represented Greenwich.

Mianus River Bridge | |

|---|---|

The bridge in 1977. The 1983 collapse happened in the eastern-most southern section (visible right) | |

| Coordinates | 41°02′12″N 73°35′31″W |

| Carries | Six lanes of |

| Crosses | Mianus River |

| Locale | Cos Cob, Greenwich, Connecticut |

| Official name | Michael L. Morano Bridge |

| Maintained by | Connecticut Department of Transportation |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Girder and floorbeam |

| Clearance below | 70 feet (21 m) |

| History | |

| Construction start | 1956 |

| Opened | 1958 |

| Rebuilt | 1992 |

| Collapsed | 1983 |

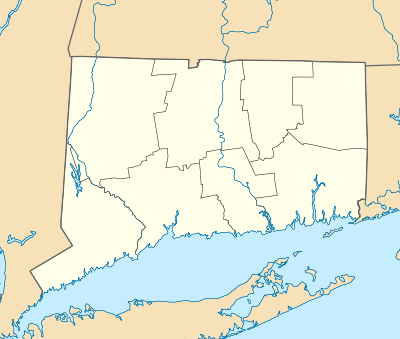

Mianus River Bridge Location in Connecticut  Mianus River Bridge Mianus River Bridge (the United States) | |

Collapse

The bridge had a 100-foot (30.5 m) section of its deck of its northbound span collapse on June 28, 1983. Three people were killed and three more were seriously injured when two cars and two tractor-trailers fell with the bridge into the Mianus River 70 feet (21.3 m) below.[1][2]

Casualties from the collapse were few because the disaster occurred at 1:30 a.m., when traffic was low on the often-crowded highway.[3]

Causes

The collapse was caused by the failure of two pin and hanger assemblies that held the deck in place on the outer side of the bridge, according to an investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board.[4] Rust formed within the bearing of the pin, exerting a force on the hanger which was beyond design limits for the retaining clamps. It forced the hanger on the inside part of the expansion joint at the southeast corner off the end of the pin that was holding it, and the load was shifted to outside hanger. The extra load on the remaining hanger started a fatigue crack at a sharp corner on the pin. When it failed catastrophically, the deck was supported at just three corners. When two heavy trucks and a car entered the section, the remaining expansion joint failed, and the deck crashed into the river below.

The ensuing investigation cited corrosion from water buildup due to inadequate drainage as a cause. During road mending some 10 years before, the highway drains had been deliberately blocked and the crew failed to unblock them when the road work was completed.[5] Rainwater leaked down through the pin bearings, causing them to rust. The outer bearings were fracture-critical and non-redundant, a design flaw of this particular type of structure. The bearings were difficult to inspect close-up, although traces of rust could be seen near the affected bearings. An alternative hypothesis has been that so-called "sludge runners" (trucking companies who carry toxic waste) would regularly open their valves while crossing the bridge to dump some of their load and that the resulting chemicals ate away at the metal structure of the bridge.[6]

The incident was also blamed on inadequate inspection resources in the state of Connecticut. At the time of the disaster, the state had just 12 engineers, working in pairs, assigned to inspect 3,425 bridges. The collapse came despite the nationwide inspection procedures brought about by the collapse of the Silver Bridge in West Virginia in December 1967.

Reaction

Northbound I-95 traffic was diverted onto US 1, and local streets in Greenwich for 6 months, causing the worst traffic problems the town had ever seen.[3] Traffic also became a large issue on the nearby Merritt Parkway (Route 15), which was used as an alternative by many motorists (though the road does not allow commercial vehicles). Only when a temporary truss carrying two lanes of northbound traffic opened in November 1983 could traffic be partially restored to the I-95 corridor. In 1984, the state began a collective effort to fund a replacement bridge.

In 1986, a $150 million bridge replacement project began. A new northbound span opened in January 1989, which allowed the temporary northbound truss to be taken out of service and demolished. On the former site, a new southbound span was built. The southbound span opened in November 1992, after which the remainder of the original bridge was taken out of service and demolished. The replacement bridge completed in 1992 is a continuous girder and floorbeam design, which eliminated the need for pin and hanger assemblies that were implicated in the collapse of the original 1958 span. Related cosmetic work and the restoration of the beachfront underneath the bridge continued to affect the area through early 1993. The new bridge, like the old one, contains six lanes of traffic, but also contains outer shoulders, a feature absent from the older and slightly narrower bridge.

After the replacement of the Mianus River Bridge, governor William O'Neill proposed a US$5.5 billion transportation spending package to pay for rehabilitation and replacement of bridges and other transportation projects in Connecticut.[3]

See also

- List of bridge failures

References

- "Mianus Bridge Disaster 1983". history.com. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- Jeffrey, Schmalz (June 24, 1984). "Year after bridge collapse, questions and pain still linger". The New York Times. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- Nguyen, Hoa (August 2, 2007). "Deadly Mianus disaster recalled". The Advocate. Stamford, Connecticut. pp. 1, A4.

- Staff (July 19, 1984) "Collapse of a Suspended Span of Inter- state Route 95 Highway Bridge over the Mianus River" National Transportation Safety Board

- "Mianus River Bridge Collapse". I-35W Bridge Collapse wiki. May 5, 2008.

- Rosoff, Stephen, Pontell, Henry, and Robert Tillman: Profit Without Honor: White-collar Crime and the Looting of America. Pearson: 7th edition 2019, p. 130

External links

- NTSB report on the collapse

- A history of the Connecticut Turnpike (I-95)

- "1983: Mianus River Bridge Collapse". WTNH News8 (YouTube). June 28, 2013. - Archival news footage of the disaster.

- 28 June 1983 on Connecticut History website