Mertensia paniculata

Mertensia paniculata, also known as the tall lungwort, tall bluebells, or northern bluebells, is an herb or dwarf shrub with drooping bright-blue, bell-shaped flowers. It is native to northwestern North America and the Great Lakes.

| Mertensia paniculata | |

|---|---|

| Mertensia paniculata (upper Matanuska River Valley, Alaska) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Boraginales |

| Family: | Boraginaceae |

| Genus: | Mertensia |

| Species: | M. paniculata |

| Binomial name | |

| Mertensia paniculata (Aiton) G. Don, 1837 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Distribution

Mertensia paniculata naturally occurs in the temperate zone of North America, and is known to thrive within the boreal forests.[2] Specifically, the northern bluebell can be found in Canada, including southern British Columbia. Within the United States, the plant can be seen in Alaska, as well as the Olympic Mountains, stretching east through Oregon to Idaho and western Montana.[3] According to the PLANTS database, M. paniculata are also spotted as far east as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.[4]

Habitat and ecology

Mertensia paniculata thrives in moist wooded or meadow areas. It is a shade-tolerant species and is present in early and late-seral communities. While it is most common in mid-succession, it has been spotted in areas in Alaska and Canada after events such as fire or logging, as an early successional community. The northern bluebell seems to have the ability to grow once more after said events due to sprouting from buried rhizomes or from vegetative parts from the surface.[5] It can also flourish under soil that is mesic,[6] has a low temperature, and has limited nutrient availability.[7] It is a perennial that, according to studies in the Yukon region, is a dominant species with precipitation of 230 mm annually, with an average temperature of −3° Celsius.[8] The months in which the flowers bloom depend on the area in which it originates, but mainly the flowering dates range from May to September.[9]

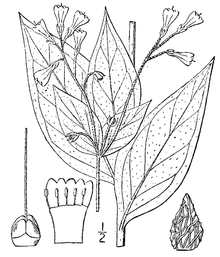

Morphology

Individuals of this species can be considered an herb-forb or a subshrub. It can sprout one to several erect stems with little to no hair at all from one long root. The stem can range from .1 to .7 meters in length. Basal leaves vary between .05 m and .2 m longitudinally and .025 m to .1 m laterally and come in a variety of shapes, including wide, elliptic-lanceolate to ovate-subcordate, eventually tapering to an acute to acuminate point at the apex. The underside of the leaf can be sparsely populated with hairs or completely smooth, and the upper surface can contain short, stiff, and slender bristles or range to completely smooth as well. Leaves are pinnately veined, simple, with petioles ranging from .1-.25 m long, becoming winged traveling up the stem of the plant. Furthermore, the leaves higher on the plant range from .05 to .18 m longitudinally and from .01 to .08 m laterally and are broad, ovate to lanceolate, with acuminate ends. Leaves are arranged in an alternate fashion as it ascends the plant. Flowers are branched on one side, forming a spiral-shaped inflorescence, otherwise known as a scorpioid cyme.[2]

Flowers, fruit, and reproduction

The bisexual flower of M. paniculata has five blue petals making up the corolla, which are commonly pink when young. Sometimes, but rarely, the corolla is white on a mature flower. The shape of the five sepals that form the calyx is linear-lanceolate and cilia are present on the margin of the sepal. The underside of the sepal can range to having either have little to no hairs or having short, stiff hairs close together, with a bristle-like texture. The tube of the northern bluebell is .0045–.007 m long, with the anthers measuring about .0022–.0033 m in length, and the style as long as or surpassing the length of the corolla.[2] The fruit of the tall lungwort are 1 to 4 small, wrinkled, single-seeded nutlets that are .0025–.005 m long, which appear in a cluster.[6] Bees seem to be the only known pollinators of the species.[10] The species also appear to be able to reproduce from a member of a clone that stays clustered around the parent plant.[11] It has been observed that the plants spread laterally by adventitious roots after fire and it has been inferred that the species is capable of reproducing by sprouting.[12]

Usage

Food and medicine

While the tall bluebell's organs are not edible whole, it has been used in the past as a pot-herb in the north and in areas of Scotland, due to its place in the borage family.[13] It also has been used for medicinal purposes. The dried leaves of the plant could be made into an herbal tea to stimulate the respiratory system.[14]

References

- "Mertensia paniculata (Aiton) G. Don". Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden. 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Elliott-Fisk, Deborah (1988). Barbour, Michael (ed.). "The boreal forest". North American Terrestrial Vegetation. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press: 33–62.

- Abrams, Leroy (1951). Illustrated Flora of the United States - Washington, Oregon, and California. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 545.

- USDA, NRCS. "The PLANTS Database". National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Wang, Geoff; Kevin Kemball (2004). "The effect of fire severity on early development of understory vegetation following a stand replacing wildfire". Session 3B - Fire Effect on Flora: Part 2. 2nd international wildland fire ecology and fire management congress: Proceedings; 2003 November 19; Orlando, FL: 11.

- Douglas, George (1998). Illustrated Flora of British Columbia. Volume 2: Dicotyledons (Balsaminaceae Through Cucurbitaceae). Victoria: B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands & Parks and B.C. Ministry of Forests. p. 401.

- Arii, Ken (1996). Factors Restricting Plant Growth In A Boreal Forest Understory: A Field Test of the Relative Importance of Abiotic and Biotic Factors (PDF) (M.Sc. thesis). University of British Columbia. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- John, Elizabeth; Roy Turkington (August 1997). "A 5-Year Study of the Effects of Nutrient Availability and Herbivory on Two Boreal Forest Herbs". Journal of Ecology. 85 (4): 419–430. doi:10.2307/2960566. JSTOR 2960566.

- Hoefs, Manfred (1979). "Flowering plant phenology at Sheep Mountain, southwest Yukon Territory". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 93 (2): 183–187.

- Macior, Lazarus Walter (1975). "The pollination ecology of Pedicularis (Scrophulariaceae) in the Yukon Territory". American Journal of Botany. 62 (10): 1065–1072. doi:10.2307/2442122.

- Hicks, Samantha; Roy Turkington (2000). "Compensatory growth of three herbaceous perennial species: the effects of clipping and nutrient availability". Canadian Journal of Botany. 78 (6): 759–767. doi:10.1139/cjb-78-6-759.

- Mann, Daniel; Lawrence Plug. "Vegetation and soil development at an upland taiga site, Alaska". Ecoscience. 6 (2): 272–285.

- Hibberd, Shirley (1900). Familiar Garden Flowers, Volume 3. Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co./Oxford University. p. 160.

- Runesson, Ulf. "Mertensia paniculata - Northern Bluebell". Faculty of Natural Resources Management - Lakehead University. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mertensia paniculata. |