Melon (chemistry)

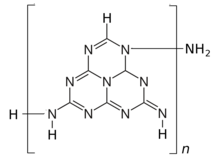

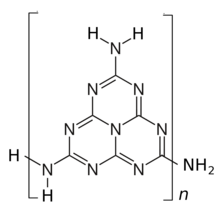

In chemistry, melon is a compound of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen of still somewhat uncertain composition, consisting mostly of heptazine units linked and closed by amine groups and bridges (–NH–, =NH, –NH

2, etc.).[2] It is a pale yellow solid, insoluble in most solvents.[1]

A careful 2001 study indicates the formula C

60N

91H

33, that consists of ten imino-heptazine units connected into a linear chain by amino bridges; that is, H(–C

6N

8H

2)–NH–)

10(NH

2).[1] However, other researchers are still proposing different structures.

Melon is the oldest known compound with the heptazine C

6N

7 core, having been described in the early 19th century. It has been little studied until recently, when it has been recognized as a notable photocatalyst and as a possible precursor to carbon nitride.[2]

History

In 1834 Liebig described the compounds that he named melamine, melam, and melon.[3][4]

The compound received little attention for a long time, due to its insolubility. In 1937 Linus Pauling showed by x-ray crystallography that the structure of melon and related compounds contained fused triazine rings.[4]

In 1939, C. E. Redemamm and other proposed a structure consisting of 2-amino-heptazine units connected by amine bridges through carbons 5 and 8.[1] The structure was revised in 2001 by T.Komatsu who proposed a tautomeric structure.[1][4]

Preparation

The compound can be extracted from the solid residue of the thermal decomposition of ammonium thiocyanate NH

4SCN at 400 °C.[1][5] (The thermal decomposition of solid melem, on the other hand, yields a graphite-like C-N material.[6])

Structure and properties

According to Komatsu, a characterized form of melon consists of oligomers that can be described as condensations of 10 units of melem tautomer with loss of ammonia NH

3. In this structure 2-imino-heptazine units are connected by amino bridges, from carbon 8 of one unit to nitrogen 4 of the next unit. X-ray diffraction data and other evidence indicate that the oligomer is planar, and he triangular heptazine cores have alternating orientations.[1]

The crystal structure of melon is orthorhombic, with estimated lattice constants a = 739.6 pm, b = 2092.4 pm and c= 1295.4 pm.[1]

Polymerization and decomposition

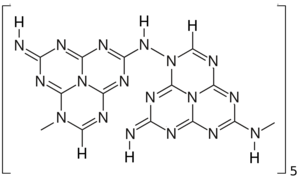

Heated to 700 °C, melon converts to a polymer of high molecular weight, consisting of longer chains with the same motif.[1]

Chlorination

Melon can be converted to 2,5,8-trichloroheptazine, a useful reagent for synthesis or heptazine derivatives.[5]

Applications

Photocatalysis

In 2009, Xinchen Wang and others observed that melon acts as a catalyst for the splitting of water into hydrogen and oxygen, or converting CO

2 back into fuel, using energy from sunlight. It was the first metal-free photocatalyst, and it was seen to enjoy a number of advantages over previous compounds, including low cost of material, simple synthesis, negligible toxicity, exceptional chemical and thermal stability. The downside is its modest efficiency, which however seems amenable to improvement by doping or nanostructuring.[7][2]

Carbon nitride precursor

Another wave of interest for melon happened in the 1990s, when theoretical computations suggested that β-C

3N

4 — a hypothetical carbon nitride compound structurally analogous to β-Si

3N

4 —might be harder than diamond. Melon seemed to be agood precursor for another form of the material, "graphitic" carbon nitride or g-C

3N

4.[2]

References

- Tamikuni Komatsu (2001)> "The First Synthesis and Characterization of Cyameluric High Polymers". Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, volume 202, issue 1, pages 19-25. doi:10.1002/1521-3935(20010101)202:1<19::AID-MACP19>3.0.CO;2-G

- Fabian Karl Keßler (2019), Structure and Reactivity of s-Triazine-Based Compounds in C/N/H Chemistry. Doctoral thesis, Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

- J. Liebig (1834): Annalen Pharmacie, 10, 1.

- Elizabeth K. Wilson (2004), "Old Molecule, New Chemistry. Long-mysterious heptazines are beginning to find use in making carbon nitride materials". Chemical & Engineering News, May 26, 2004. Online version accessed on 2009-06-30.

- Dale R. Miller, Dale C. Swenson, and Edward G. Gillan (2004): "Synthesis and Structure of 2,5,8-Triazido-s-Heptazine: An Energetic and Luminescent Precursor to Nitrogen-Rich Carbon Nitrides". Journal of the American Chemical Society, volume 126, issue 17, pages 5372-5373. doi:10.1021/ja048939y

- Barbara Jürgens, Elisabeth Irran, Jürgen Senker, Peter Kroll, Helen Müller, Wolfgang Schnick (2003): "Melem (2,5,8-Triamino-tri-s-triazine), an Important Intermediate during Condensation of Melamine Rings to Graphitic Carbon Nitride: Synthesis, Structure Determination by X-ray Powder Diffractometry, Solid-State NMR, and Theoretical Studies". Journal of the American Chemical Society, volume 125, issue 34, pages 10288-10300. doi:10.1021/ja0357689

- Xinchen Wang, Kazuhiko Maeda, Arne Thomas, Kazuhiro Takanabe, Gang Xin, Johan M. Carlsson, Kazunari Domen, and Markus Antonietti (2009): "A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light", Nature Materials volume 8, pages 76-80. doi:10.1038/nmat2317