Meghadūta

Meghadūta (Sanskrit: मेघदूत literally Cloud Messenger)[1] is a lyric poem written by Kālidāsa, considered to be one of the greatest Sanskrit poets.

About the poem

A poem of 120[2] stanzas, it is one of Kālidāsa's most famous works. The work is divided into two parts, Purva-megha and Uttara-megha. It recounts how a yakṣa, a subject of King Kubera (the god of wealth), after being exiled for a year to Central India for neglecting his duties, convinces a passing cloud to take a message to his wife at Alaka on Mount Kailāsa in the Himālaya mountains.[3] The yakṣa accomplishes this by describing the many beautiful sights the cloud will see on its northward course to the city of Alakā, where his wife awaits his return.

In Sanskrit literature, the poetic conceit used in the Meghaduta spawned the genre of Sandesa Kavya or messenger poems, most of which are modeled on the Meghaduta (and are often written in the Meghaduta's Mandākrāntā metre). Examples include the Hamsa-sandesha, in which Rama asks a Hansa Bird to carry a message to Sita, describing sights along the journey.

In 1813, the poem was first translated into English by Horace Hayman Wilson. Since then, it has been translated several times into various languages. As with the other major works of Sanskrit literature, the most famous traditional commentary on the poem is by Mallinātha.

The great scholar of Sanskrit literature, Arthur Berriedale Keith, wrote of this poem: "It is difficult to praise too highly either the brilliance of the description of the cloud’s progress or the pathos of the picture of the wife sorrowful and alone. Indian criticism has ranked it highest among Kalidasa’s poems for brevity of expression, richness of content, and power to elicit sentiment, and the praise is not undeserved."[4]

An excerpt is quoted in Canadian director Deepa Mehta's film, Water. The poem was also the inspiration for Gustav Holst's The Cloud Messenger Op. 30 (1909–10).

Simon Armitage appears to reference Meghaduta in his poem ‘Lockdown’.

It is believed the picturesque Ramtek near Nagpur has inspired Kalidas to write the poem.[5]

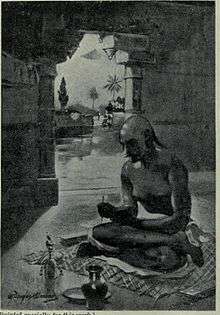

Visualisation of Meghadūta

Meghadūta describes several scenes and is a rich source of inspiration for many artists.

An example are the drawings by Nana Joshi.[6]

Composer Fred Momotenko wrote the composition 'Cloud-Messenger', music for a multimedia performance with recorder, dance, projected animation and electronics in surround audio. The world premiere was at Festival November Music, with Hans Tuerlings (choreography), Jasper Kuipers (animation), Jorge Isaac (blockflutes) and dancers Gilles Viandier and Daniela Lehmann.[7]

See also

- Mandākrāntā metre

- Hamsa-Sandesha

- Sanskrit literature

- Sanskrit drama

- Sandesh Rasak

- Sandesa Kavya

Editions

- Wilson, Horace Hayman (1813). The Mégha Dúta, Or, Cloud Messenger: A Poem, in the Sanscrit Language. Calcutta: College of Fort William. Retrieved 11 November 2010.. 2nd ed 1843 Introduction, text with English verse translation, and assorted footnotes.

- Johann Gildemeister, ed. (1841), Kalidasae Meghaduta et Cringaratilaka ex recensione: additum est glossarium, H.B. König. Sanskrit text, with introduction and some critical notes in Latin.

- The Megha-dūta (3 ed.), Trübner & co., 1867 With Sanskrit text, English translation and more extensive notes separately.

- Colonel H. A. Ouvry (1868), The Megha dūta: or, Cloud messenger, Williams and Norgate . A prose translation.

- Ludwig Fritze (1879), Meghaduta, E. Schmeitzner. German translation.

- The Megha duta; or, Cloud messenger: a poem, in the Sanscrit language, Upendra Lal Das, 1890. Hayman's translation, with notes and translation accompanying the Sanskrit text.

- Exhaustive notes on the Meghaduta, Bombay: D.V. Sadhale & Co., 1895 . Text with Mallinātha's commentary Sanjīvanī. Separate sections for English translation, explanation of Sanskrit phrases, and other notes.

- Eugen Hultzsch, ed. (1911), Kalidasa's Meghaduta: Edited from manuscripts With the Commentary of Vallabhadeva and Provided With a Complete Sanskrit-English Vocabulary, Royal Asiatic society, London

- T. Ganapati Sastri, ed. (1919), Meghaduta with the commentary of Daksinavartanatha

- Sri sesaraj Sarma Regmi, ed. (1964), Meghadutam of mahakavi Kalidasa (in Sanskrit and Hindi), chowkhmba vidybhavan varanasi-1

- Ramakrishna Rajaram Ambardekar, ed. (1979), Rasa structure of the Meghaduta - A critical study of Kalidaas's Meghaduta in the light of Bharat's Rasa Sootra (in English and Sanskrit)

Translations

The Meghadūta has been translated many times in many Indian languages.

- Dr. Jogindranath Majumdar translated Meghaduta in Bengali keeping its original 'Mandakranta Metre' for the first time published in 1969

- Acharya Dharmanand Jamloki Translated Meghduta in Garhwali and was well known for his work.

- Moti BA translated Meghduta in Bhojpuri Language.

References

- "Meghdutam". Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Pathak, K. B. (1916), Kalidasa's Meghaduta, pp. xxi–xxvii.

- Wilson (1813), page xxi.

- Keith, A. B. (1928). A History of Sanskrit Literature, p. 86.

- "History | District Nagpur,Government of Maharashtra | India". Retrieved 2020-07-02.

- Joshi, Nana. "A Visual Interpretation of Kalidas' Meghadūta". Joshi Artist. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Cloud-Messenger".

| Sanskrit Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

External links

- Text

- Translations

- Translation by Arthur W. Ryder at The Internet Sacred Text Archive

- Translation by C. John Holcombe (Available as ebook)

- Partial text of the Megadhuta, with word-for-word translation

- Illustrated translation by Jaffor Ullah and Joanna Kirkpatrick

- A literal prose translation Translating Kalidasa with examples from Meghaduta.

- Megadhuta in Garhwali Translation by Acharya Dharmanand Jamloki.

- Recordings

- Dr. Bipin Kumar Jha. Chanted recitation.

- Sung to music composed by Vishwa Mohan Bhatt. (Also here)

- Recitation of first verse by Sangeeta Gundecha. (Two other verses, 1.5 and 2.26, are recited from minute 5:50 onwards.)

- About the work

- Illustrating the Meghaduta: "Illustrated catalogue of the plants and trees of Kalidasa’s Meghaduta".

- A summary by Chandra Holm

- Notes on issues in translation by Holcombe

- A Review of a book of translation.