Megalomyrmex symmetochus

Megalomyrmex symmetochus is a species of ant in the subfamily Myrmicinae. It is native to Panama.[1]

| Megalomyrmex symmetochus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. symmetochus |

| Binomial name | |

| Megalomyrmex symmetochus Wheeler, 1925 | |

M. symmetochus was discovered by William M. Wheeler in late July 1924 in the fungus gardens of the attine Sericomyrmex amabilis of Barro Colorado Island.[2]

Description

Workers are 3 to 3.5 mm long, with small, feebly convex eyes, that are probably adapted to living within the dark fungal gardens of their host. Very small ocelli are only sometimes present. Workers are yellowish red, with mandibles, funiculi, the posterior half of the first segment of the gaster and the sutures of the thorax and pedicels brown. The tip of the gaster is yellowish.[2]

The female is almost 4 mm long. She has larger eyes than the workers and distinct ocelli. Otherwise, they look very similar to workers. Each ocellus has a black margin internally. The wings are yellowish hyaline and iridescent, with veins and pterostigma pale yellow. The membranes of the wings are distinctly pubescent.[2]

Males are almost 3 mm long. They bear very large eyes and ocelli. Their body form is very similar to that of workers and females, but with smooth sides of the thorax. The wings have longer pubescence that in the female. Males are brownish yellow, with a little darker gaster and slightly paler antennae and legs. The eyes and a spot along the inner border of each ocellus are black.[2]

Behavior

M. Symmetochus often live among and take from the gardens of fungus-growing ants, sometimes usurping the gardens.[3] In some populations they coexist with fungus-growing hosts >80% of the time.[4] They number their hosts as much as 1:3.[5] Young queens stealthily invade fungus-growing colonies and start their own lineage in the fungus garden.[6] Then, they clip the wings of the hosts' virgin queens, but not the males.[6]

When their hosts live near predators who destroy the nests and destroy their gardens, M. Symmetochus serves as protection of their host colonies. Hundreds of worker ants live throughout the nest of the host, and when invaders attack, individuals recruit the others inside to defend the nest. Also, these ants have been observed projecting their stings, leaving two isomers of 3-butyl-5-hexylpyrrolizidine, marking the nest with the scent of its toxin.[5] It seems that some species avoid nests with their marked scent. When there are no invaders, M. Symmetochus commonly have aggressive conflict with their hosts.[6] Therefore, it seems that when M. Symmetochus lives with a host with no outside danger, they serve as parasites, but when the hosts live near other threats, they have a mutualistic relationship with their hosts.[5]

References

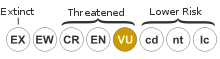

- Social Insects Specialist Group 1996. Megalomyrmex symmetochus. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Archived June 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Downloaded on 10 August 2007.

- Wheeler, W.M. (1925). "A new guest-ant and other new Formicidae from Barro Colorado Island, Panama". Biological Bulletin 49: 150-181.

- Adams, R. M.; Mueller, U. G.; Schultz, T. R.; Norden, B. (December 2000). "Agro-predation: usurpation of attine fungus gardens by Megalomyrmex ants". Die Naturwissenschaften. 87 (12): 549–554. Bibcode:2000NW.....87..549A. doi:10.1007/s001140050777. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 11198197.

- Wheeler, William Morton (September 1925). "A NEW GUEST-ANT AND OTHER NEW FORMICIDÆ FROM BARRO COLORADO ISLAND, PANAMA". The Biological Bulletin. 49 (3): 150–181. doi:10.2307/1536460. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1536460.

- Boomsma, Jacobus J.; Nash, David R.; Jones, Tappey H.; Illum, Anders A.; Liberti, Joanito; Adams, Rachelle M. M. (2013-09-24). "Chemically armed mercenary ants protect fungus-farming societies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (39): 15752–15757. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11015752A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1311654110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3785773. PMID 24019482.

- Adams, Rachelle M. M.; Shah, Komal; Antonov, Lubomir D.; Mueller, Ulrich G. (2012). "Fitness consequences of nest infiltration by the mutualist-exploiter Megalomyrmex adamsae". Ecological Entomology. 37 (6): 453–462. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2012.01384.x. ISSN 1365-2311.