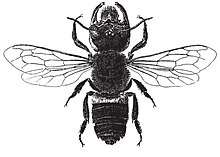

Megachile pluto

Megachile pluto, also known as Wallace's giant bee or raja ofu/rotu ofu (king/queen of the bees in Indonesian),[2] is a very large Indonesian resin bee. It is the largest known living bee species. It was believed to be extinct until several specimens were discovered in 1981. There were no further confirmed sightings until two were collected and sold on eBay in 2018. A live female was found and filmed for the first time in 2019.[3]

| Megachile pluto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Megachilidae |

| Genus: | Megachile |

| Subgenus: | Megachile (Callomegachile) |

| Species: | M. pluto |

| Binomial name | |

| Megachile pluto B. Smith, 1860 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

Wallace's giant bee is a black resin bee with well developed and large jaws. The species exhibits strong sexual dimorphism: females may reach a length of 38 mm (1.5 in), with a wingspan of 63.5 mm (2.5 in), but males only grow to about 23 mm (0.9 in) long. Only females have large jaws.[4] M. pluto is believed to be the largest living bee species, and remains the largest extant bee species described.[5] It is "as long as an adult's thumb".[6] Wallace's giant bee is easily distinguished from other bees due to its large size and jaws, but also a notable white band on the abdomen.[7]

Distribution and habitat

Wallace's giant bee has only been reported from three islands of the North Moluccas in Indonesia: Bacan, Halmahera and Tidore. Very little is known about its distribution and habitat requirements, although it is thought that it is restricted to primary lowland forests. The islands have become home to oil palm plantations that now occupy much of the former native habitat. This has caused the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to label this species as Vulnerable.[1]

Discovery and rediscovery

The species was originally collected by Alfred Russel Wallace in 1858, and given the common name "Wallace's giant bee"; it is also known as the "giant mason bee". It was thought to be extinct until it was rediscovered in 1981 by Adam C. Messer, an American entomologist, who found six nests on the island of Bacan and other nearby islands.[7] The bee is among the 25 "most wanted" lost species that are the focus of Global Wildlife Conservation's "Search for Lost Species" initiative.[8]

After 1981, the bee was not observed in the wild for the next 37 years. In 2018, two specimens were collected in Indonesia, one on Bacan in February and the other on Halmahera in September. They were subsequently sold on eBay, highlighting the lack of protection that is afforded to the rare species.[9] In 2019, a single female was found by Clay Bolt, living in a termite nest in Indonesia.[10] This specimen was filmed and photographed before being released.[6][11][12]

Ecology

Wallace's giant bees build communal nests inside active nests of the tree-dwelling termite Microcerotermes amboinensis, which may have served to hide their existence even from island residents. The bee uses tree resin to build compartments inside the termite nest, which protects its galleries. Female bees leave their nests repeatedly to forage for resin, which comes frequently from Anisoptera thurifera. The bee's large jaws assist in resin gathering: the female makes large balls of resin which are held between the jaws. The association of the bee with the termite may be obligate.[7][1]

See also

- Asian giant hornet - the largest living hornet

- List of largest insects

References

- Kuhlmann, M. (2014). "Megachile pluto". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T4410A21426160. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T4410A21426160.en.

- Bolt, Clay (2019-02-21). "Rediscovering Wallace's giant bee". Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- Briggs, Helen (2019-02-22). "World's biggest bee found alive". Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- Simon, Matt (2019-02-21). "The Triumphant Rediscovery of the Biggest Bee on Earth". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- Quenqua, Douglas (2019-02-21). "The World's Largest Bee Is Not Extinct". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- Briggs, Helen (21 February 2019). "World's biggest bee found alive". BBC News – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Messer, A. C. (1984). "Chalicodoma pluto: The World's Largest Bee Rediscovered Living Communally in Termite Nests (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae)". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 57 (1): 165–168. JSTOR 25084498.

- "The Search for Lost Species". Global Wildlife Conservation. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- Vereecken, Nicolas (2018). "Wallace's Giant Bee for sale: implications for trade regulation and conservation". Journal of Insect Conservation. 22 (5–6): 807–811. doi:10.1007/s10841-018-0108-2.

- Simon, Matt (21 February 2019). "The Triumphant Rediscovery of the Biggest Bee on Earth". Wired. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Main, Douglas (21 February 2019). "World's largest bee, once presumed extinct, filmed alive in the wild". National Geographic.

- Bolt, Clay. "Wallace's Giant $9,000 Bee". National Geographic. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2018-11-07.

External links