Media freedom in the European Union

Media freedom in the European Union is a fundamental right that applies to all member states of the European Union and its citizens, as defined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights as well as the European Convention on Human Rights.[2]:1 Within the EU enlargement process, guaranteeing media freedom is named a "key indicator of a country's readiness to become part of the EU".[3]

Media freedom, including freedom of the press, is the principal platform for ensuring freedom of expression and freedom of information, referring to the right to express value judgments and the right of allegation of facts, respectively. While the term media freedom refers to the absence of state monopoly or excessive state intrusion, Media pluralism is understood in terms of lack of private control over media, meaning the avoidance of concentrated private media ownership.[2]

The annual World Press Freedom Day is celebrated on 3 May.[4]

Press freedom and democracy

Media Freedom is inherent to the decision making process in a well-functioning democracy, enabling citizens to make their political choices based on independent and pluralistic information and thus is an important instrument to form public opinion. The expression of a variety of opinions is needed in public debate to give the citizens the possibility to assess and choose among a wide range of opinions. The more pluralistic and articulated the opinions, the greater is the legitimising effect that media has on the wider democratic political process. Press freedom is often described as a watchdog over public power, underlining its significant role as an observer and informer of the public opinion on government actions.[2]

Freedom of expression refers back to individual journalists', as well as to press institutions' rights. In other words, its significance covers both the individual right of each journalist to express his or her opinion and the press' right as an institution to inform people. To guarantee the protection of free media, state authorities not only underlie the negative obligation to abstain from intrusion, but as well to the positive commitment to promote media freedom and act as a guarantor against intrusion of public as well as private actors.[2]:2

Legislative framework and law enforcement

International law provisions and enforcement

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as well as Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights recognise freedom of expression and freedom of information as fundamental Human rights.[5][6] Even though these documents are recognised universally, their enforcement depends widely on the state's will on adapting measures of implementation.

On the European level, the Council of Europe provides a legal framework through the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), whose enforcement is assured through the European Court of Human Rights' (ECtHR) jurisdiction.[2] ECHR Article 10 on Freedom of expression says:

"1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

2.The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary." [7]

As observable in the citation, within the ECHR freedom of expression is not recognised as an absolute right, meaning it can be restricted if there are other competing fundamental rights or legitimate objectives necessary for democratic society. These might be data protection, the right to privacy, reputation or criminal justice. However, the restriction needs to be proportional to the achievement of the competing objective and press freedom and needs "very high requirements before any restrictions can be imposed on the freedom of the press by the public authorities."[2] Even if Press freedom takes the function of a democracy guarantor, it does not only protect materials dealing with political issues, but is applied as well to tabloid journalism. However, the more significant a specific journalistic item is to form public opinion, the higher priority needs to be given to press freedom when it is weighed up against other legitimate interests.[2]

The ruling of the ECtHR looks back at a long history of jurisprudence regarding violations of article 10, starting in the late 1970s. In particular, ECtHR protects investigative journalism, journalistic sources of information and whistle-blowers and stresses the negative effect of sanctions against journalistic activities, as leading to auto-censorship and so hindering the purpose of journalism to inform people. On the other hand, the court has strengthened the protection of the right to privacy against reporting whose only purpose is to nourish people's curiosity.[2]

European Union legislation and law enforcement

In the European Union, member states have committed to respect the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (The rights under Article 11 of the EU Charter correspond to those given by the ECHR under article 10), which entered into force with the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 as Article 6(1) TEU. However, long before the entry into force of the treaty, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) recognised EU fundamental rights as general principles of EU law and considered them part of the legal framework on which it bases its jurisprudence.[2]

In practice, the impact of fundamental EU laws and values on EU member states' behaviour is often limited.[2] While indicating freedom of expression as a "key indicator of a country's readiness to become part of the EU",[3] once a country has entered the Union, the EU institutions have a limited possibility to enforce the respect of fundamental rights and values, including those on freedom of expression and information. This phenomenon is also known as the Copenhagen Dilemma, an issue addressed, among others, by the European Parliament resolution entitled EU Charter: standard settings for media freedom across the EU [8], adapted in May 2013. The document stresses the importance of monitoring and supervising the development of national legislations regarding media freedom in the EU member states and proposes to attribute this task to the EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA).[2]

Regarding television services specifically, the 2010 Audiovisual Media Services Directive establishes that hate speech and speech harming minors must be prohibited in all member states.[9] What is more, the 2018 Audiovisual Media Services Directive is set to instate the following position on media freedom:

"In order to strengthen freedom of expression, and, by extension, to promote media pluralism and avoid conflicts of interest, it is important for Member States to ensure that users have easy and direct access at any time to information about media service providers. It is for each Member State to decide, in particular with respect to the information which may be provided on ownership structure and beneficial owners."[10]

This text was adopted by the European Parliament on 2 October 2018.

Monitoring media freedom in the EU

There is a wide range of international governmental and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that advocate for media freedom within the EU and the EU Candidate, Potential Candidate, as well as Eastern Partnership countries.[11] The organisations' work includes theoretical activities such as producing reports on the state of media freedom in different countries, as well as giving practical help, such as financial or legal support, to people active in journalism.

Governmental Organizations

- Council of Europe. Branches relevant to media freedom: Committee of experts on protection of journalism and safety of journalists (MSI-JO), Committee on Culture, Science, Education and Media, Commissioner for Human Rights[12]

- European Commission Directorate-Generals relevant to media freedom: DG Communications Networks, Content and Technology/DG Connect, DG Enlargement/DG NEAR)[13]

- European Parliament Parliamentary Committees dealing with media freedom: Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs/LIBE, Subcommittee on Human Rights/DROI[14]

- OSCE: OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

- UNESCO Division of Freedom of Expression and Media Development[15]

Non-Governmental Organizations

International

- ARTICLE 19

- Committee to Protect Journalists

- Freedom House (Freedom of the Press and Freedom on the Net annual reports)[16]

- Index on Censorship (Mapping Media Freedom project,[17] Freedom of Expression Awards[18])

- Global Forum for Media Development[19]

- Human Rights Watch (Section on Press Freedom[20])

- Ethical Journalism Network[21]

- International Press Institute (Media Law Database,[22] On The Line project[23])

- Media Legal Defence Initiative

- Reporters Without Borders

European/Regional

- Institute of European Media Law (EMR)[24]

- Access Info Europe[25]

- European University Institute Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CPMF)[26]

- European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

- European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

- European Journalism Centre (EJC)

- Journalismfund.eu[27]

- South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

References

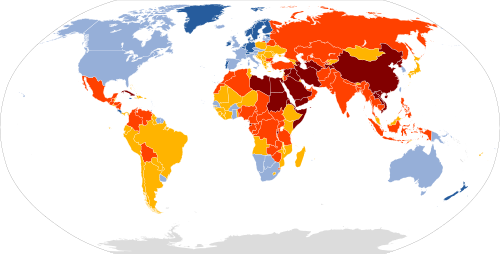

- "2020 World Press Freedom Index". Reporters Without Borders. 2020.

- Maria Poptcheva, Press freedom in the EU Legal framework and challenges, EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service, Briefing April 2015

- "European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations". European Commission. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "World Press Freedom Day 2016". UNESCO. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- "UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights". United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Universal Declaration of Human Rights" (PDF). United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms". Council of Europe. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "European Parliament resolution of 21 May 2013 on the EU Charter". European Parliament. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "DIRECTIVE 2010/13/EU". EUR-lex. Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Revision of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive - Plenary Document". europarl.europa(.eu). © European Union. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- "Stakeholders". Resource Centre. European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- "Stakeholders/Council of Europe". Resource Centre. European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- "Stakeholders/European Commission". Resource Centre. European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- "Stakeholders/European Parliament". Resource Centre. European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- UNESCO Division of Freedom of Expression and Media Development

- Freedom of the Press and Freedom on the Net

- Mapping Media Freedom

- Freedom of Expression Awards Archived 27 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Global Forum for Media Development

- Section on Press Freedom

- Ethical Journalism Network

- Media Law Database

- on the line Archived 2 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine: tracking digital attacks against journalists

- Institute of European Media Law

- Access Info Europe

- Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom Archived 20 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Journalismfund.eu