Meckel's cartilage

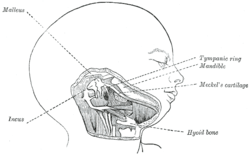

In humans, the cartilaginous bar of the mandibular arch is formed by what are known as Meckel’s cartilages (right and left) also known as Meckelian cartilages; above this the incus and malleus are developed. Meckel's cartilage arises from the first pharyngeal arch.

| Meckel's cartilage | |

|---|---|

Head and neck of a human fetus at eighteen weeks, with Meckel’s cartilage and hyoid bar exposed. | |

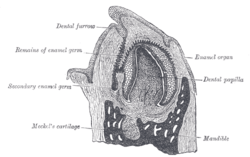

Mandible of human fetus 95 mm. long. Inner aspect. Nuclei of cartilage stippled. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | first pharyngeal arch |

| Gives rise to | incus, malleus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cartilago arcus pharyngei primi |

| TE | E4.0.3.3.3.1.3 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The dorsal end of each cartilage is connected with the ear-capsule and is ossified to form the malleus; the ventral ends meet each other in the region of the symphysis menti, and are usually regarded as undergoing ossification to form that portion of the mandible which contains the incisor teeth.

The intervening part of the cartilage disappears; the portion immediately adjacent to the malleus is replaced by fibrous membrane, which constitutes the sphenomandibular ligament, while from the connective tissue covering the remainder of the cartilage the greater part of the mandible is ossified.

Johann Friedrich Meckel, the Younger discovered this cartilage in 1820.

Evolution

The Meckelian Cartilage, also known as "Meckel's Cartilage", is a piece of cartilage from which the mandibles (lower jaws) of vertebrates evolved. Originally it was the lower of two cartilages which supported the first branchial arch in early fish. Then it grew longer and stronger, and acquired muscles capable of closing the developing jaw.[1]

In early fish and in chondrichthyans (cartilaginous fish such as sharks), the Meckelian Cartilage continued to be the main component of the lower jaw. But in the adult forms of osteichthyans (bony fish) and their descendants (amphibians, reptiles(including birds), mammals), the cartilage was covered in bone – although in their embryos the jaw initially develops as the Meckelian Cartilage. In all tetrapods the cartilage partially ossifies (changes to bone) at the rear end of the jaw and becomes the articular bone, which forms part of the jaw joint in all tetrapods except mammals.[1]

In some extinct mammal groups like eutriconodonts, the Meckel's cartilage still connected otherwise entirely modern ear bones to the jaw.[2]

Additional images

Vertical section of the mandible of an early human fetus. X 25.

Vertical section of the mandible of an early human fetus. X 25.

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 66 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- The Gill Arches: Meckel's Cartilage, palaeos. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Jing Meng, Mesozoic mammals of China: implications for phylogeny and early evolution of mammals, Natl Sci Rev (December 2014) 1 (4): 521–542. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwu070 First published online: October 17, 2014

External links

- synd/2049 at Who Named It?