Maxwell House Hotel

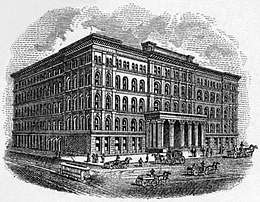

The Maxwell House Hotel was a major hotel in downtown Nashville. Because of its stature, seven US Presidents and other prominent guests stayed there over the years. It was built by Colonel John Overton Jr. and named for his wife, Harriet (Maxwell) Overton. The architect was Isaiah Rogers.[1]

| Maxwell House Hotel | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Construction started | 1859 |

| Completed | 1869 |

| Demolished | 1961 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Isaiah Rogers |

Former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest was inducted into the Ku Klux Klan in this hotel in 1866. The first national meeting of the KKK took place at the hotel in April 1867. It later became the namesake of Maxwell House coffee. It was demolished in 1961.

History

As Nashville developed, local businessmen believed it was time for a major hotel. Colonel John Overton Jr. decided to build one and named it for his wife, Harriet (Maxwell) Overton. He hired architect Isaiah Rogers to design the structure.[1] Construction began in 1859 using mostly enslaved labor.[2] The outbreak of the American Civil War caused a suspension of construction on the hotel.

Nashville fell to the Union Army in 1862 and was occupied afterward until the end of the war. The army took over the unfinished hotel, using it as a barracks, prison, and hospital.[1][2] In September 1863, several Confederate prisoners were killed when a staircase collapsed.[3]

The hotel was said to be haunted by a Southern belle and two brothers, who had been assigned as guards during the war. One killed the other and the girl in a jealous rage and died when the staircase collapsed while he was moving the bodies.[4]

Some of the spaces in the hotel were used. In the fall of 1866, former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest was inducted into the Ku Klux Klan, a newly formed secret vigilante group. Politician John W. Morton performed the honors in Room 10 of the Maxwell House Hotel. Forrest was made the Grand Wizard of the Invisible Empire.[5] Chapters of the new association sprang up across the South, and the first national meeting of the KKK took place at the hotel in April 1867.[6][7]

What local citizens called "Overton's Folly"[3] was finally completed and opened in fall 1869; total costs were $500,000.[1] The Maxwell House was Nashville's largest hotel, with five stories and 240 rooms. It advertised steam heat, gas lighting, and a bath on every floor. Rooms cost $4 a day, including meals.[1] Located on the northwest [8]corner of Fourth Avenue North and Church Street, the hotel had its front entrance, flanked by eight Corinthian columns, on Fourth Avenue in the "Men's Quarter". A separate entrance for women was on Church Street. The main lobby featured mahogany cabinetry, brass fixtures, gilded mirrors, and chandeliers. It had ladies' and men's parlors, billiard rooms, barrooms, shaving "saloons", and a grand staircase to the large ball or dining room.[1] George R. Calhoun, the brother of silversmith William Henry Calhoun, managed a jewelry store in the hotel.[9]

The hotel was at its height from the 1890s to the early 20th century. Its Christmas dinner featuring calf's head, black bear, and opossum, and other unusual delicacies became famous. Hotel guests included Jane Addams, Sarah Bernhardt, William Jennings Bryan, Enrico Caruso,[3] "Buffalo Bill" Cody, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Annie Oakley, William Sydney Porter (O. Henry),[10] General Tom Thumb, Cornelius Vanderbilt, George Westinghouse,[1] and Presidents Andrew Johnson, Rutherford B. Hayes, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt, William McKinley, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson.[2]

Coffee connection

A reported comment by President Theodore Roosevelt that a cup of coffee he drank was "good to the last drop" was used as the advertising slogan for Maxwell House coffee, which was served at and named after the hotel.[11] The coffee brand is still in operation, and is now owned by Kraft Heinz.

Destruction

After being used for some years as a residential hotel, the Maxwell House Hotel was destroyed by fire on Christmas Night 1961.[3][12] The ServiceSource Tower was later built on this site at 201 4th Avenue North. The Millennium Maxwell House Hotel, opened in the 21st century, was named for the old Maxwell House.

References

- Ophelia Paine, "Maxwell House Hotel," The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, online edition 2002, accessed November 12, 2011.

- Kathy Walker, "Maxwell House Hotel", Historical Marker Database, November 6, 2009, accessed January 14, 2010.

- Jackie Sheckler Finch, The Insiders' Guide to Nashville, 7th ed. 2009, p. 28.

- Ken Traylor and Delas M. House, Jr., Nashville Ghosts and Legends, Charleston, South Carolina: Haunted America/The History Press, 2007, ISBN 9781596293243, pp. 45-46.

- Rose, Laura Martin (1914). The Ku Klux Klan or Invisible Empire. New Orleans, Louisiana: L. Graham co. p. 22 – via Internet Archive.

- Mark V. Wetherington, "Ku Klux Klan," The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, updated January 1, 2010, accessed February 11, 2013.

- Historical Fact Sheet Archived 2008-07-25 at the Wayback Machine, Study Circles Resource Center, Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts (pdf).

- "Maxwell House Hotel Historical Marker".

- Caldwell, Benjamin Hubbard (1988). Tennessee Silversmiths. Winston-Salem, N.C.: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. p. 49. ISBN 9780945578017. OCLC 837245410.

- Traylor and House, p. 45.

- The Tennessee Encyclopedia implies he drank it at the hotel, but other versions of the story hold that it was at Andrew Jackson's home, The Hermitage: "'Good to the Last Drop' ... or was it? Teddy Roosevelt's 1907 visit to The Hermitage," Archived 2007-11-12 at the Wayback Machine Tennessee History for Kids, accessed January 14, 2010. Based on Bill Carey, Fortunes, Fiddles and Fried Chicken: A Nashville Business History, 2000.

- "Hotel in Nashville Destroyed by Fire," New York Times, December 26, 1961, p. 31.

External links