Maxima clam

The maxima clam (Tridacna maxima), also known as the small giant clam, is a species of bivalve mollusc found throughout the Indo-Pacific region. They are much sought after in the aquarium trade, as their often striking coloration mimics that of the true giant clam; however, the maximas maintain a manageable size, with the shells of large specimens typically not exceeding 20 centimetres (7.9 in) in length.

| Maxima clam | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Subclass: | Heterodonta |

| Order: | Cardiida |

| Family: | Cardiidae |

| Genus: | Tridacna |

| Species: | T. maxima |

| Binomial name | |

| Tridacna maxima Röding, 1798 | |

Description

Bivalves have two valves on the mantle. These siphon water through the body to extract oxygen from the water using the gills and to feed on algae.[2] The maxima is less than one-third the size of the true giant clam (Tridacna gigas).

Shell

Adults develop a large shell that adheres to the substrate by its byssus, a tuft of long, tough filaments that protrude from a hole next to the hinge.

Mantle

When open, the bright blue, green or brown mantle is exposed and obscures the edges of the shell which have prominent, distinctive furrows. The attractive colours of the small giant clam are the result of crystalline pigment cells. These are thought to protect the clam from the effects of intense sunlight, or bundle light to enhance the algae's photosynthesis.[2] Maxima produce the color white in their mantle by clustering red, blue and green cells, while individual T. derasa cells are themselves multi-colored.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The small giant clam has the widest range of all giant clam species. It is found in the oceans surrounding east Africa, India, China, Australia, Southeast Asia, the Red Sea and the islands of the Pacific.[1][4]

Found living on the surface of reefs or sand, or partly embedded in coral,[5] the small giant clam occupies well-lit areas, due to its symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic algae, which require sunlight for energy production.[2]

Biology

A sessile mollusc, the small giant clam attaches itself to rocks or dead coral and siphons water through its body, filtering it for phytoplankton, as well as extracting oxygen with its gills. However, it does not need to filter-feed as much as other clams since it obtains most of the nutrients it requires from tiny photosynthetic algae known as zooxanthellae.[2]

Beginning life as a tiny fertilised egg, the small giant clam hatches within 12 hours, becoming a free-swimming larva. This larva then develops into another, more developed, larva which is capable of filter-feeding. At the third larval stage, a foot develops, allowing the larva to alternately swim and rest on the substrate. After eight to ten days, the larva metamorphoses into a juvenile clam, at which point it can acquire zooxanthellae and function symbiotically.[2] The juvenile matures into a male clam after two or three years, becoming a hermaphrodite when larger (at around 15 centimetres in length). Reproduction is stimulated by the lunar cycle, the time of day, and the presence of other eggs and sperm in the water. Hermaphroditic clams release their sperm first followed later by their eggs, thereby avoiding self-fertilisation.[2]

References

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Maxima clam" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

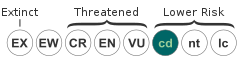

- Wells, S. (1996). "Tridacna maxima". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T22138A9362499. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T22138A9362499.en.

- Ellis, S. (1998) Spawning and early larval rearing of giant clams (Bivalvia: Tridacnidae). Center for Tropical and Subtropical Aquaculture, 130: 1–55.

- "Giant clams could inspire better color displays and solar cells". www.gizmag.com. January 20, 2016. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- Huelsken, T., Keyse, J., Liggins, L., Penny, S., Treml, E.A., Riginos, C. (2013) A Novel Widespread Cryptic Species and Phylogeographic Patterns within Several Giant Clam Species (Cardiidae: Tridacna) from the Indo-Pacific Ocean. PLoS ONE, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080858.

- Wells, S.M., Pyle, R.M. and Collins, N.M. (1983) The IUCN Invertebrate Red Data Book. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tridacna maxima. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Tridacna maxima |