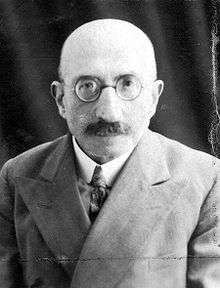

Max Beer

Moses "Max" Beer (1864–1943) was an Austrian-born Marxist journalist, economist, and historian. Beer is best remembered as an early writer on the topic of imperialism and for a series of books, published in translation in several countries, which examined the nature of class struggle throughout human history.

Max Beer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 10, 1864 |

| Died | April 30, 1943 London |

| Occupation | Marxist historian |

Biography

Early years

Moses Beer, known to all by the nickname "Max," was born August 10, 1864 in the small town of Tarnobrzeg, Galicia, which was then part of the Austrian Empire. He was of ethnic Jewish heritage.[1] Beer's father, Nathan Beer, worked as a kosher butcher.[2]

As a young boy Beer was educated in a Jewish Cheder, but he was moved to a local Christian school at the age of 12.[2] He finished his secondary education at the age of 15 and then spent a year learning French, with a view to working as a tutor.[2]

Journalistic career

In May 1889, Beer moved to Germany, settling in Remscheid, where he learned the newspaper trade as a compositor for the Bergische Tageblatt.[2] He developed radical political views, however, and moved to Leipzig in 1892 where he began to make the acquaintance of various leaders of the socialist movement.[2] He shortly relocated in Magdeburg where he became assistant editor of the Magdeburger Volksstimme, a socialist newspaper.[2]

This political activity put him at odds with the conservative government of the country and after eight months in the editorial chair Beer was arrested under charges of having incited class struggle and insulted the German authorities.[1] Beer was convicted of these charges and sentenced to 14 months in prison.[1]

In June 1894, Beer emigrated to Great Britain.[1] He studied at the London School of Economics from 1895 to 1896, gaining an interest in the emerging intellectual topic of imperialism.[1] He left school to resume his journalistic career, covering the controversial French treason case against Alfred Dreyfus for the press.[1]

Following his stint in Paris, Beer emigrated again, this time to the United States, arriving in New York City in 1898.[1] Beer covered the Spanish–American War and emerging American imperial policy in former Spanish possessions as a correspondent for the Berlin socialist newspaper Vorwärts (Forward) and the theoretical monthly of the Social-Democratic Party of Germany, Die Neue Zeit (The New Time), among others.[1] Beer also wrote for the Encyclopaedia Judaica in this interval.[1]

In 1901, Vorwäerts lost its London correspondent, Eduard Bernstein, who returned home to Germany and Beer was tapped by the paper as his replacement.[3] He remained in that position until 1911.[2] Beer left his place at the Vorwäerts to pursue more scholastic writing. He signed a contract to produce a history of British socialism in the German language, a book which was published in 1913.[2]

Return to Germany

The coming of World War I made Beer's position in Great Britain untenable and he was deported in 1915 as a so-called "enemy alien."[3] Back in Germany he worked as a translator for the German central trade union organization and as a freelance journalist.[2]

In 1919, Beer was named as editor of Die Glocke (The Bell), a socialist periodical owned by Alexander Parvus. He would remain in that position until 1921.[3] During the next several years, Beer would author a biography of Karl Marx and a series of works of history which examined the changing forms of class struggle through the centuries. Written in German, these works would be published in translation into English and other languages, gaining Beer an international reputation as a Marxist historian.

Communist years

In 1927, Beer was invited to Moscow to work at the Marx-Engels Institute by that facility's director, David Ryazanov.[3] Beer would remain in the Soviet Union through 1928.[2]

Upon his return to Germany, Beer became active in the German Communist Party. He lived in the city of Frankfurt am Main, where he worked at the Institut fur Sozialforschung.[3]

Death and legacy

When the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933, Beer fled to London, where he would remain for the rest of his life. Beer was naturalized as a British citizen in 1939.[2]

Max Beer died of tuberculosis in London on April 30, 1943.[2]

There is a street in the Mitte district of Berlin named after Beer.

Footnotes

- Richard B. Day and Daniel Gaido, eds. and trans., Discovering Imperialism: Social Democracy to World War I. (2011) Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012; pg. 95.

- Donald MacRaild, "Max Beer," in Thomas A. Lane (ed.), Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders: A-L. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995; pp. 68-69.

- Day and Gaido, Discovering Imperialism, pg. 96.

Works

Books

- Jean Jaurès: Socialist und Staatsman. Berlin: Druck und Verlag für Sozialwissenschaft, 1918.

- The Pioneers of Land Reform: Thomas Spence, William Ogilvie, Thomas Paine. London: G. Bell, 1920.

- The Life and Teaching of Karl Marx. T. C. Partington and H. J. Stenning, trans. London: National Labour Press, 1921.

- Social Struggles in Antiquity. London: L. Parsons, 1922.

- Social Struggles in the Middle Ages. H. J. Stenning, trans. London: L. Parsons, 1924.

- Social Struggles and Socialist Forerunners. H. J. Stenning, trans. London: L. Parsons, 1924.

- Social Struggles and Thought (1750-1860). H. J. Stenning, trans. London: L. Parsons, 1925.

- Social Struggles and Modern Socialism. H. J. Stenning, trans. London: L. Parsons, 1925.

- A Guide to the Study of Marx: An introductory course for classes and study circles. London, Labour Research Department, Sylabus Series No. 14. Undated (1930?) Second Edition 32pp

- The League on Trial: A Journey to Geneva. Boston: Houghton & Mifflin, 1933.

- Fifty Years of International Socialism. London, G. Allen & Unwin, 1935. —Autobiography.

- Early British Economics: from the XIIIth to the middle of the XVIIIth century London, G. Allen & Unwin, 1938.

- A History of British Socialism. In Two Volumes. London : G. Allen & Unwin, 1940.

- The General History of Socialism and Social Struggles. In Two Volumes. New York, Russell & Russell, 1957.

- An Inquiry into Physiocracy. New York, Russell & Russell, 1966.

Articles

- "Modern English Imperialism," (Nov. 1897) in Richard B. Day and Daniel Gaido, eds. and trans., Discovering Imperialism: Social Democracy to World War I. (2011) Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012; pp. 95–108.

- "The United States in 1898," (Dec. 1898) in Day and Gaido, Discovering Imperialism, pp. 109–124.

- "The United States in 1899," (Nov. 1899) in Day and Gaido, Discovering Imperialism, pp. 125–128.

- "Reflections on England's Decline," (March 1901) in Day and Gaido, Discovering Imperialism, pp. 239–248.

- "Social Imperialism," (Nov. 1901) in Day and Gaido, Discovering Imperialism, pp. 249–264.

- "Party Projects in England," (Jan. 1902) in Day and Gaido, Discovering Imperialism, pp. 265–274.

- "Imperialist Policy," (Dec. 1902) in Day and Gaido, Discovering Imperialism, pp. 275–284.

- "Imperialist Literature," (Dec. 1906) in Day and Gaido, Discovering Imperialism, pp. 285–290.

Further reading

- "Max Beer," Social Democrat, vol. 6, no. 8 (August 15, 1902), pp. 227–228.

External links

- Works by Max Beer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Max Beer at Internet Archive

- Max Beer Internet Archive, Marxists Internet Archive, www.marxists.org/