Maternal to zygotic transition

Maternal to zygotic transition (MZT, also known as Embryonic Genome Activation) is the stage in embryonic development during which development comes under the exclusive control of the zygotic genome rather than the maternal (egg) genome. The egg contains stored maternal genetic material mRNA which controls embryo development until the onset of MZT. After MZT the diploid embryo takes over genetic control [1]. This requires both zygotic genome activation (ZGA) and degradation of maternal products. This process is important because it is the first time that the new embryonic genome is utilized and the paternal and maternal genomes are used in combination (ie. different alleles will be expressed). The zygotic genome now drives embryo development.

MZT is often thought to be synonymous with midblastula transition (MBT), but these processes are, in fact, distinct.[2] However, the MBT roughly coincides with ZGA in many metazoans,[3] and thus may share some common regulatory features. For example, both processes are proposed to be regulated by the nucleocytoplasmic ratio.[4][5] MBT strictly refers to changes in the cell cycle and cell motility that occur just prior to gastrulation.[2][3] In the early cleavage stages of embryogenesis, rapid divisions occur synchronously and there are no "gap" stages in the cell cycle.[2] During these stages, there is also little to no transcription of mRNA from the zygotic genome,[4] but zygotic transcription is not required for MBT to occur.[2] Cellular functions during early cleavage are carried out primarily by maternal products – proteins and mRNAs contributed to the egg during oogenesis.

Zygotic genome activation

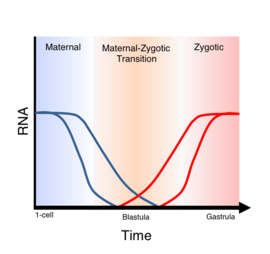

Generalized diagram showing levels of maternal and zygotic mRNA levels over the course of embryogenesis. Maternal to zygotic transition (MZT) is the period during which zygotic genes are activated and maternal transcripts are cleared. After Schier (2007). |

To begin transcription of zygotic genes, the embryo must first overcome the silencing that has been established. The cause of this silencing could be due to several factors: chromatin modifications leading to repression, lack of adequate transcription machinery, or lack of time in which significant transcription can occur due to the shortened cell cycles.[6] Evidence for the first method was provided by Newport and Kirschner's experiments showing that nucleocytoplasmic ratio plays a role in activating zygotic transcription.[4][7] They suggest that a defined amount of repressor is packaged into the egg, and that the exponential amplification of DNA at each cell cycle results in titration of the repressor at the appropriate time. Indeed, in Xenopus embryos in which excess DNA is introduced, transcription begins earlier.[4][7] More recently, evidence has been shown that transcription of a subset of genes in Drosophila is delayed by one cell cycle in haploid embryos.[8] The second mechanism of repression has also been addressed experimentally. Prioleau et al. show that by introducing TATA binding protein (TBP) into Xenopus oocytes, the block in transcription can be partially overcome.[9] The hypothesis that shortened cell cycles can cause repression of transcription is supported by the observation that mitosis causes transcription to cease.[10]. The generally accepted mechanism for the initiation of embryonic gene regulatory networks in mammals is that there are multiple waves of MZT. In mouse, the first of these occurs in the zygote, where expression of a few pioneering transcription factors gradually increases the expression of target genes downstream. This induction of genes leads to a second major MZT event [11]

Clearing of maternal transcripts

To eliminate the contribution of maternal gene products to development, maternally-supplied mRNAs must be degraded in the embryo. Studies in Drosophila have shown that sequences in the 3' UTR of maternal transcripts mediate their degradation[12] These sequences are recognized by regulatory proteins that cause destabilization or degradation of the transcripts. Recent studies in both zebrafish and Xenopus have found evidence of a role for microRNAs in degradation of maternal transcripts. In zebrafish, the microRNA miR-430 is expressed at the onset of zygotic transcription and targets several hundred mRNAs for deadenylation and degradation. Many of these targets are genes that are expressed maternally.[13] Similarly, in Xenopus, the miR-430 ortholog miR-427 has been shown to target maternal mRNAs for deadenylation. Specifically, miR-427 targets include cell cycle regulators such as Cyclin A1 and Cyclin B2.[14]

References

- Lee, Miler T.; Bonneau, Ashley R.; Takacs, Carter M.; Bazzini, Ariel A.; Divito, Kate R.; Fleming, Elizabeth S.; Giraldez, Antonio J. (2013). "Nanog, Pou5f1 and SoxB1 activate zygotic gene expression during the maternal-to-zygotic transition". Nature. 503 (7476): 360–364. doi:10.1038/nature12632. PMC 3925760. PMID 24056933.

- Baroux C, Autran D, Gillmor CS, et al. (2008). "The Maternal to Zygotic Transition in Animals and Plants". Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 73: 89–100. doi:10.1101/sqb.2008.73.053. PMID 19204068.

- Tadros W, Lipshitz HD (2009). "The maternal to zygotic transition: a play in two acts". Development. 136 (18): 3033–42. doi:10.1242/dev.033183. PMID 19700615.

- Newport J, Kirschner M (1982). "A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: I. characterization and timing of cellular changes at the midblastula stage". Cell. 30 (3): 675–86. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(82)90272-0. PMID 6183003.

- Pritchard DK, Schubiger G (1996). "Activation of transcription in Drosophila embryos is a gradual process mediated by the nucleocytoplasmic ratio". Genes Dev. 10 (9): 1131–42. doi:10.1101/gad.10.9.1131. PMID 8654928.

- Schier AF (2007). "The Maternal-Zygotic Transition: Death and Birth of RNAs". Science. 316 (5823): 406–7. Bibcode:2007Sci...316..406S. doi:10.1126/science.1140693. PMID 17446392.

- Newport J, Kirschner M (1982). "A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: II. control of the onset of transcription". Cell. 30 (3): 687–96. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(82)90273-2. PMID 7139712.

- Lu X, Li JM, Elemento O, Tavazoie S, Wieschaus EF (2009). "Coupling of zygotic transcription to mitotic control at the Drosophila mid-blastula transition". Development. 136 (12): 2101–2110. doi:10.1242/dev.034421. PMC 2685728. PMID 19465600.

- Prioleau MN, Huet J, Sentenac A, Mechali M (1994). "Competition between chromatin and transcription complex assembly regulates gene expression during early development". Cell. 77 (3): 439–49. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90158-9. PMID 8181062.

- Shermoen AW, O'Farrell PH (1991). "Progression of the cell cycle through mitosis leads to abortion of nascent transcripts". Cell. 67 (2): 303–10. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90182-X. PMC 2755073. PMID 1680567.

- Xue, Zhigang; Huang, Kevin; Cai, Chaochao; Cai, Lingbo; Jiang, Chun-yan; Feng, Yun; Liu, Zhenshan; Zeng, Qiao; Cheng, Liming; Sun, Yi E.; Liu, Jia-yin; Horvath, Steve; Fan, Guoping (2013). "Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing". Nature. 500 (7464): 593–597. Bibcode:2013Natur.500..593X. doi:10.1038/nature12364. PMC 4950944. PMID 23892778.

- Tadros W, Lipshitz HD (2005). "Setting the stage for development: mRNA translation and stability during ooccyte maturation and egg activation in Drosophila". Dev Dyn. 232 (3): 593–608. doi:10.1002/dvdy.20297. PMID 15704150.

- Giraldez AJ, Mishima Y, Rihel J, Grocock RJ, Van Dongen S, Inoue K, Enright AJ, Schier AF (2006). "Zebrafish miR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs". Science. 312 (5770): 75–9. Bibcode:2006Sci...312...75G. doi:10.1126/science.1122689. PMID 16484454.

- Lund E, Liu M, Hartley RS, Sheets MD, Dahlberg JE (2009). "Deadenylation of maternal mRNAs mediated by miR-427 in Xenopus laevis embryos". RNA. 15 (12): 2351–63. doi:10.1261/rna.1882009. PMC 2779678. PMID 19854872.