Marylander (train)

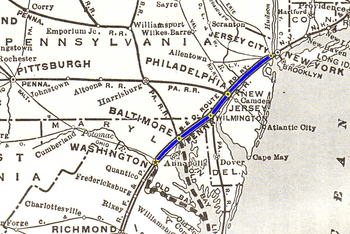

The Marylander was a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) afternoon passenger train between New York City and Washington, D.C., operated by the B&O in partnership with the Reading Railroad and the Central Railroad of New Jersey between Jersey City, New Jersey, and Washington, D.C.. Other intermediate cities served were Philadelphia, Wilmington, Delaware, and Baltimore, Maryland.[1][2] The Marylander's origin can be traced back to the late 1890s, when the B&O began its famed Royal Blue Line service between New York and Washington. Operating as #524 northbound and #525 southbound, the trains were called the New York Express and the Washington Express, respectively, in the 1910s and 1920s. The Marylander and its predecessors offered a high level of passenger amenities, such as parlor cars with private drawing rooms, full dining car service, deluxe lounge cars, and onboard radio and telephone service. The Marylander made history in 1948 when it was the first moving train to offer onboard television reception.[3] It was one of B&O's faster trains on the route, maintaining a four-hour schedule until its discontinuation in October 1956 due to declining patronage.

.jpg)

History

First introduced by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) as one of the New York–Washington Royal Blue Line trains in the 1890s, the Marylander began life as Train #524, the New York Express, departing Washington at 1 p.m. Southbound, the Washington Express operated as Train #525 with a mid-afternoon departure from Jersey City.[4]

By the late 1920s, Trains #524 and #525 were among the B&O's ten daily passenger trains in each direction between Washington and New York. On May 29, 1929, the B&O dubbed its mid-afternoon deluxe Washington-New York train the Columbian.[4] By the early 1930s, intense competition from the Pennsylvania Railroad in the New York–Washington market prompted the B&O to air condition the train in 1932, the first railroad to do so.[1] Also introduced were the richly-appointed Martha Washington-series dining cars, celebrated for their decor and fresh Chesapeake Bay cuisine served on Dresden china in ornate cars with glass chandeliers and colonial-style furnishings. Dining car specialties included oysters and Chesapeake Bay fish served with cornmeal muffins.[5] In September 1941, the B&O introduced a new Washington–Chicago all-coach train, calling it the Columbian.[6] The Columbian's former afternoon schedule between New York and Washington was renamed the Marylander.[5][6]

Along with most other rail passenger services in the U.S. during World War II, the Marylander enjoyed a surge in passenger traffic between 1942 and 1945 as volume doubled to 1.2 million passengers annually on B&O's eight daily New York–Washington trains.[1] Following the end of the war, however, passenger volumes soon dropped below prewar levels and B&O discontinued one of its eight daily New York–Washington trains. Between the late 1940s and the mid-1950s, the Marylander and the line's flagship Royal Blue continued to serve New York, along with three New York–St. Louis, Missouri trains: the Metropolitan Special, National Limited, and Diplomat, and two Chicago trains: the Capitol Limited and Shenandoah.[7]

Onboard television

On October 7, 1948, the Marylander made history when a live television broadcast was first shown aboard a moving train, using a receiver operated by Bendix Corporation technicians.[3] The second game of the 1948 World Series in Boston between the Cleveland Indians and the Boston Braves was watched by the Marylander's passengers, along with a Federal Communications Commissioner, news reporters, and B&O officials. As the New York-bound train departed Washington's Union Station at 1:35 p.m. and hurtled northward on B&O's right-of-way through Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey at an average speed of 80 miles per hour (129 km/h), technicians tuned the receiver to the strongest signal. An Associated Press reporter observing the demonstration said, "Technically, it was surprisingly good."[3] The New York Times reported the following day that "only when the train passed under bridges or steel structures, or was out of the range of television transmitters, was there any indication that the receiver was operating under unusual circumstances".[3] A B&O official observing the experiment said that reception was mostly "as good as one finds in the average home".[3]

Demise

The overwhelming market dominance of the Pennsylvania Railroad was evident when it introduced the 18-car stainless steel Morning Congressional and Afternoon Congressional streamliners in 1952.[1] By the late 1950s, most U.S. passenger trains suffered a steep decline in patronage as the traveling public abandoned trains in favor of airplanes and automobiles, utilizing improved Interstate Highways. The Marylander and B&O's other New York–Washington passenger trains were no exception, as operating deficits approached $5 million annually and passenger volume declined by almost half between 1946 and 1957.[2][8] As financial losses mounted, the B&O discontinued the Marylander in October, 1956.[1] Less than two years later, on April 26, 1958, the railroad discontinued all of its remaining passenger trains between Baltimore and New York, ending service altogether to the latter city.

En route

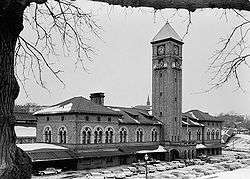

In Baltimore, the Marylander used the B&O's Mount Royal Station (39.3055°N 76.6197°W), at the north end of the Howard Street tunnel in the fashionable Bolton Hill neighborhood.

Designed by Baltimore architect E. Francis Baldwin and opened in 1896, Mount Royal Station is a blend of modified Romanesque and Renaissance styling and built of Maryland granite trimmed with Indiana limestone, with a red tile roof and a 150-foot (46 m) clocktower. The station's interior featured marble mosaic flooring, a fireplace, and rocking chairs.[9]

Because the B&O had no direct rail service across the Hudson River into New York City, the Marylander and B&O's other New York-bound trains terminated at the Central Railroad of New Jersey's Jersey City Terminal. Passengers were then transferred to buses that met the train right on the platform. These buses were ferried across the Hudson River into Manhattan and Brooklyn, where they proceeded to various "stations" around the city on four different routes, including the Vanderbilt Hotel, Wanamaker's, Columbus Circle, and Rockefeller Center.[4]

Schedule and equipment

The Marylander operated on afternoon schedules in both directions, with a 1 p.m. departure from Washington, D.C., Union Station and a 5 p.m. departure from Jersey City, arriving at its destination four hours later.[1] In the Marylander's final year of operation, the Official Guide listed the following schedule for train # 525, the southbound Marylander, as of February 1956 (unconditional stops denoted in blue, bus connections in yellow):

| City | Departure time |

|---|---|

| New York (Rockefeller Center) | 4:00 p.m. |

| New York (Grand Central Terminal) | 4:10 p.m. |

| Jersey City, New Jersey | 5:00 p.m. |

| Elizabeth, New Jersey | 5:17 p.m. |

| Plainfield, New Jersey | 5:30 p.m. |

| Philadelphia, Pa. | 6:40 p.m. |

| Wilmington, Del. | 7:06 p.m. |

| Baltimore, Maryland (Mt. Royal Station) | 8:12 p.m. |

| Baltimore, Maryland (Camden Station) | 8:17 p.m. |

| Washington, D.C. (Union Station) | 8:35 p.m. |

| Source: Official Guide of the Railways, p. 418[7] | |

Northbound, the Marylander departed Washington at 1:00 p.m. as train # 504, arriving at Jersey City 5:00 p.m.:

| City | Departure time |

|---|---|

| Washington, D.C. (Union Station) | 1:00 p.m. |

| Baltimore, Maryland (Camden Station) | 1:36 p.m. |

| Baltimore, Maryland (Mt. Royal Station) | 1:44 p.m. |

| Wilmington, Del. | 2:50 p.m. |

| Philadelphia, Pa. | 3:20 p.m. |

| Plainfield, New Jersey | 4:31 p.m. |

| Elizabeth, New Jersey | 4:44 p.m. |

| Jersey City, New Jersey | 5:00 p.m. |

| New York (Grand Central Terminal) | 5:45 p.m. |

| New York (Rockefeller Center) | 5:50 p.m. |

| Source: Official Guide of the Railways, p. 418[7] | |

Between the 1930s and its discontinuance in 1956, the Marylander was equipped with air-conditioned coaches, parlor cars with private drawing rooms, a lounge car, and a full dining car serving complete meals.[7][10] Beginning in mid-August 1947, onboard telephone service was provided, making the B&O (along with the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroad) one of the first three railroads in the U.S. to offer telephone service on its trains, using a forerunner of cell phone technology.[7][11] The train's accelerated four-hour schedule necessitated the use of track pans to replenish the Marylander's 4-6-2 President-class Pacific steam locomotives' water supply without stopping, to maintain as fast a schedule as possible. By September 1947, the Marylander and all other B&O New York–Washington passenger trains were powered by diesel locomotives.[1]

References

- Herbert H. Harwood, Jr., Royal Blue Line. Sykesville, Maryland: Greenberg Publishing, 1990 (ISBN 0-89778-155-4), pp. 161–167.

- Morgan, David P. (August 1958). "Royal Blue Line 1890—1958". Trains Magazine. Kalmbach Publishing. 18 (8).

- "Train Television Shows Ball Game" (pdf). The New York Times. October 8, 1948. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- Harwood, Royal Blue Line, pp. 121–126.

- Kratville, William W. (1962). Steam Steel and Limiteds. A Saga of the Great Varnish Era. Omaha, NE: Barnhart Press. OCLC 1301983.

- Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 153.

- Official Guide of the Railways. New York: National Railway Publication Co., February 1956, pp. 414–418.

- Frederick N. Rasmussen (2008-04-27). "Lonesome whistle blew for last time". The Baltimore Sun. p. 21A. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- Stephen J. Salamon, David P. Oroszi, and David P. Ori, Baltimore and Ohio – Reflections of the Capitol Dome. Silver Spring, Maryland: Old Line Graphics, 1993 (ISBN 1-879314-08-8), p. 24.

- Harwood, Royal Blue Line, p. 145.

- Bert Pennypacker, "Dial direct at 110 mph", Trains Magazine, April, 1968.