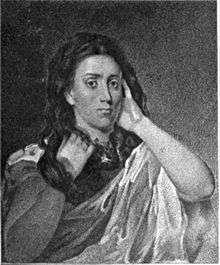

Mary Ann Duff

Mary Ann Duff (born Mary Ann Dyke; 1794 – 5 September 1857) was an English tragedienne, in her time regarded as the greatest upon the American stage.[1] She was born in London, England, and died in New York City, United States.

Biography

Mary Ann Dyke and her younger sisters Elizabeth and Ann were all born in London. Their father was an Englishman, employed in the service of the British East India Company, and he died abroad while they were children. Their mother prepared them for the stage under James Harvey D'Egville, a ballet-master of the King's Theatre, London.[2]

Early career

The Dyke sisters made their first appearance in 1809, at a Dublin theatre and were described as "remarkable for their beauty and winning disposition."[2] While Mary was performing in Dublin, she met Irish poet Thomas Moore who proposed to her but was rejected as Mary had already formed an attachment to the man who became her husband. Moore turned his attention to her sister Elizabeth whom he married soon after.[2] Mary Ann married in her sixteenth year John R. Duff (1787–1831),[3] an Irish actor. (The youngest sister Ann married William Murray, the brother of Harriet Murray), but died soon after the marriage.)[2] John Duff had been a classmate of Moore at Trinity College, where he had read law, but was drawn to the stage. He was seen in Dublin by actor Thomas Apthorpe Cooper who recommended him to Powell and Dickson of the Boston Theatre. He was immediately engaged and he and Mary, barely sixteen, moved to America in 1810.[2] In 1817, John became a partner in the Boston Theatre but relinquished his share after three years.[4]

American career

Mary Ann Duff first appeared in Boston as Juliet on 31 December 1810 with her husband as Romeo. The part of Mercutio was played by John Bernard.[2] Although one critic remarked on her attractiveness, he felt that her youth made her lack experience and conception.[2]

Her next performance was on 3 January 1811, where she played Lady Anne in Richard III with George Frederick Cooke in the title rôle. She followed it with Lady Rodolpha Lumbercourt to his Sir Pertinax MacSycophant in Charles Macklin's Man of the World; Charlotte to his Sir Archy MacSarcasm in Love a la Mode by the same author; and Lady Percy to his Falstaff in Henry IV, Part 1.[2] Other roles she played at this time were Miranda, with her husband as Marplot, in The Busy Bodie by Susanna Centlivre; and Eliza Ratcliff, with John Bernard as Sheva, in The Jew by Richard Cumberland. She also appeared in the pantomimes Oscar and Malvina by William Reeve, in which she also danced; and Brazen Mask by James Hewitt. On 29 April 1811 the Duffs appeared at a benefit in which Mary danced a solo while her husband performed in The Three and the Deuce by Prince Hoare. The latter was so popular that he would go on to repeat this triple-role performance more than eighty times over the course of his career. Mary's first season in Boston ended with her playing Victoria in Hannah Cowley's A Bold Stroke for a Husband.[2]

In July, the company made its annual migration to Providence, Rhode Island. Ellen Darley (née Westwray) retired as leading "juvenile lady"; as a result, Mary stepped up and succeeded to most of her characters.[2]

Other tragic rôles included Ophelia, Desdemona, and Lady Macbeth. In 1821, also in Boston, she played Hermione in The Distrest Mother, by Ambrose Philips, an adaptation of Racine's Andromaque. So powerful was her performance that Edmund Kean feared it might be forgotten that he was the "star." She first appeared in New York City in 1823, as Hermione, to the Orestes of the elder Booth.

In 1828, she played at Drury Lane, London, but soon returned to America where Mr. Duff died in 1831. He had been for some time in poor health and had declined in professional popularity, while his wife, at first viewed as inferior to him in ability, had surpassed and eclipsed him. After her husband's death, Mary had a hard struggle with poverty, as she was the mother of ten children and actors, even of the best order, were poorly paid in those days. In 1826, in New York, Mr. and Mrs. Duff received jointly, during ten weeks, a salary of only $55 a week, together with the net proceeds of one benefit. In 1835, she played for the last time in New York and was married to Joel G. Sevier, of New Orleans in 1836. Her farewell to the stage in 1838 occurred there.[5]

Final years

She lived in New Orleans, renounced the Stage, left the Catholic faith, and became a Methodist. For many years her life was devoted to works of piety and benevolence. About 1854, the once great and renowned actress, took up her abode with her youngest daughter, Mrs. I. Reillieux, at 36 West Ninth Street, New York City, where, on 5 September 1857, she died. Although she suffered from cancer, the immediate cause of death was an internal haemorrhage.

An article in The Philadelphia Sunday Mercury, 9 August 1874, written by James Rees, relates the strange circumstances of her burial. According to that authority, the body of Mrs. Duff-Sevier was laid in the receiving tomb at Greenwood, 6 September 1857, and shortly afterward that of her daughter, Mrs. Reillieux, was likewise laid there; but on 15 April 1858, both those bodies were thence removed and were finally buried in the same grave, which is No. 805, in Lot 8,999, in that part of the cemetery known as "The Hill of Graves," – the certificate describing them as "Mrs. Matilda I. Reillieux & Co." The grave was then marked with a headstone, inscribed with the words, "My Mother and Grandmother." There seems to have been a purpose to conceal the identity of Mrs. Sevier with Mrs. Duff, and to hide the fact that the mother of Mrs. Reillieux had ever been on the stage, – but the grave of the actress was finally discovered and restored.

References

- New International Encyclopedia

- Joseph Norton Ireland (1882) Mrs. Duff, James R. Osgood and Co., Boston

- John Bernard (1887) Retrospections of America, 1797–1811, Harper and Brothers, New York

- Abel Bowen (1888) Bowen's Picture of Boston, Otis, Broaders and Company, Boston

- Garff B. Wilson (Mar. 1955) "Forgotten Queen of the American Stage: Mary Ann Duff", Educational Theatre Journal, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 11–15

Bibliography

- The Wallet of Time

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. Missing or empty

|title=(help)