Martin Droeshout

Martin Droeshout (/ˈdruːʃaʊt/; April 1601 – c.1650) was an English engraver of Flemish descent, who is best known as illustrator of the title portrait for William Shakespeare's collected works, the First Folio of 1623, edited by John Heminges and Henry Condell, fellow actors of the Bard. Nevertheless, Droeshout produced other more ambitious designs in his career.

Droeshout's artistic abilities are typically regarded as limited. The Shakespeare portrait shares many clumsy features with Droeshout's work as a whole. Benjamin Roland Lewis notes that "virtually all of Droeshout's work shows the same artistic defects. He was an engraver after the conventional manner, and not a creative artist."[1]

Life

Droeshout was a member of a Flemish family of engravers who had migrated to England to avoid persecution for their Protestant beliefs. His father, Michael Droeshout, was a well established engraver, and his older brother, John, was also a member of the profession. His mother, Dominique Verrike, was his father's second wife. His uncle, also called Martin Droeshout (1560s- c. 1642), was an established painter. No direct documentation survives about the life of Droeshout beyond the record of his baptism.[2]

Because of the multiple family members, including his uncle with the same name, it is difficult to separate out the younger Martin's biography from surviving information. There is little doubt that a number of engravings were made by the same individual, on stylistic grounds and the similarities of the signatures and monograms used.[2]

Though Droeshout's engraving of Shakespeare is his earliest dated work, there is reason to believe he was already an established engraver, possibly having already produced the allegorical print The Spiritual Warfare.[3] He made at least twenty four engravings in London between 1623 and 1632. These included portraits and more complex allegorical works, the most elaborate of which was Doctor Panurgus, an adaptation of an earlier engraving by Matthaeus Greuter.

Ever since the identification of the surviving records of the Droeshout family, there has been uncertainty about whether "Martin Droeshout" the engraver was the brother or the son of Michael Droeshout, though Lionel Cust in the original Dictionary of National Biography asserted what became the majority view, that the younger Martin Droeshout was the more likely candidate.[4] In 1991 historian Mary Edmund argued that his uncle, Martin Droeshout the Elder, may have been both a painter and engraver, and that there was no evidence that the younger Droeshout ever worked as an engraver at all. She stated that the Droeshout oeuvre should all be attributed to the elder Martin. Her views were asserted in the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[5] More recent research by June Schlueter reaffirms the traditional attribution of the engravings to the younger Droeshout.[6]

Some time between 1632 and 1635 Droeshout emigrated to Spain, settling in Madrid. This is known because he produced a number of signed engravings there from 1635 to 1640. Art historian Christiaan Schuckman believes that Droeshout's move to Spain must have been caused by, or led to, a conversion to Catholicism, as many of these works depict Catholic saints and use Catholic symbolism.[7] Martin's namesake, Martin the Elder, is known to have remained in London and was a staunch member of the local Dutch Protestant community throughout his life.[7]

While in Spain Droeshout also seems to have anglicised his name to "Droeswoode" ("hout" being Dutch for "wood"), possibly because of negative attitudes to the Dutch in Spain at the time.[7] There are no known records of Droeshout after 1640. Martin is not mentioned in his brother's will, dated 1651, which may mean that he was dead by this date, or that his family had severed links with him due to his Catholicism.

Works

Shakespeare

Droeshout would have been beginning his career as an engraver when he was commissioned to create the portrait of Shakespeare, who had died when Martin was fifteen years old. He was 21 when he received the commission. The engraving is probably based on a pre-existing painting or drawing. Since Martin's uncle of the same name was an established painter, it was suggested by E. A. J. Honigmann that the elder Martin may have made the original image, which could explain why his young relation was given the commission for the engraving.[7] Tarnya Cooper argues that the poor drawing and modelling of the doublet and collar suggests that Droeshout was copying a lost drawing or painting that only depicted Shakespeare's head and shoulders. The body was added by the engraver himself, as was common practice.[8]

Other English prints

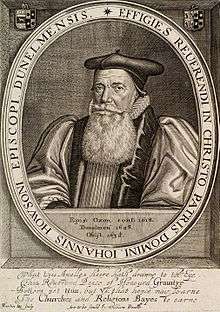

Droeshout later created portrait engravings depicting John Foxe, Gustavus Adolphus, John Donne, John Howson, George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham and other notables.[9]

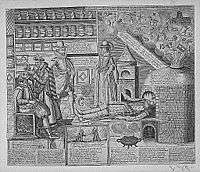

He also created more ambitious allegorical, mythical and satirical designs. These included The Spiritual Warfare, engraved around the same time as the Shakespeare image. This depicts the devil's army besieging a stronghold held by a "Christian Soldier bold" guarded by figures representing the Christian virtues.[10] It has been proposed that this design may have influenced John Bunyan to write The Holy War.[11] It appears to have been reprinted in 1697 in the wake of the success of Bunyan's books.[11]

Droeshout created an illustration depicting the suicide of Dido which functioned as a frontispiece to Robert Stapylton's verse translation of the fourth book of Virgil's Aeneid.[12] Among his more complex works are several engraved plates for Thomas Heywood's The Hierarchy of the Blessed Angels, for which Droeshout was one of five engravers who created plates.

Droeshout's most complex independent print is "Doctor Panurgus", an allegory of the follies of modern life, depicting figures representing Country, Town and Court life being treated by the doctor. The design "has a complicated ancestry",[13] being an adaptation of an earlier print by Greuter, which itself drew on emblem book designs. Droeshout, or perhaps an unknown person who designed it, seems to have made a number of specific elaborations of the image, including extensive text, adding extra characters and English and Latin phrases, notably verses explaining how the doctor is purging the three figures of their respective moral illnesses. He pours "Wisdome and Understanding" down the throat of an ignorant rustic and smokes the brain of the "gallant" (courtier) in an oven to burn away the vanity in it (represented by various images going up in smoke). Two other figures wait to have their own brains smoked. Inset are other designs referring to the religious controversy of the era over pluralism.[14] The whole is filled with boxed passages of satirical moral verse of unknown authorship.

Spanish prints

Droeshout's ten known Spanish engravings are all on subjects with distinctly Catholic significance, differing dramatically in that respect to works he had been producing in Britain up to 1632, one of the last of which was an allegory of the theology of presbyterian Puritan Alexander Henderson. Stylistically the engravings remain very similar. The portrait of Francisco de la Peña is similar in its modelling and the drawing of head-shape to the Shakespeare print.[7] His earliest Spanish work depicted the coat of arms of leading Counter-Reformation Spanish statesman Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares. His most explicitly Catholic design depicts the "Church as Warrior stamping out Heresy, Error and Temerity", a frontispiece to the Novissimus Librorum Prohibitorum et Expurgatorum Index.[7]

Notes and references

Notes

- Lewis 1969, pp. 553–6.

- Schlueter 2007.

- Jones 2001.

- Cust 1888.

- Edmond 2008.

- Schlueter 2007, p. 242.

- Schuckman 1991.

- Cooper 2006, p. 48.

- NPG n.d.

- Jones 2002, p. 360.

- Zinck 2007.

- Godfrey 1978.

- Griffiths 1998, pp. 146–8.

- Jones 2006.

References

- Cooper, Tarnya (2006). "1. William Shakespeare, from the First Folio, c.1623". In Cooper, Tarnya (ed.). Searching for Shakespeare. Yale University Press / National Portrait Gallery. ISBN 9780300116113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cust, Lionel Henry (1888). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 16. London: Smith, Elder & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edmond, Mary (2008) [2004]. "Droeshout, Martin (1565x9–c.1642)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8054.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Godfrey, Richard T. (1978). Printmaking in Britain: a general history from its beginnings to the present day. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814729731. OCLC 4529464.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, Antony (1998). The Print in Stuart Britain: 1603-1689. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0714126074.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Malcolm (2001). "English Broadsides - I". Print Quarterly. XVIII (2): 149–63. ISSN 0265-8305.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Malcolm (2002). "The English Print". In Hattaway, Michael (ed.). A Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture. Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0626-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Malcolm (November 2006). "'Doctor Panurgus'". British Printed Images to 1700. Retrieved 14 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Benjamin Roland (1969) [1940]. The Shakespeare documents: facsimiles, transliterations, translations, & commentary. 2. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0837146225.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Martin Droeshout (1601-1650?)". National Portrait Gallery. n.d. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Schlueter, June (2007). "Martin Droeshout Redivivus: Reassessing the Folio Engraving of Shakespeare". Shakespeare Survey. Cambridge University Press. 60, Theatres for Shakespeare: 237–51. doi:10.1017/CCOL052187839X.018. ISBN 9781139052726 – via Cambridge Core.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schuckman, Christiaan (1991). "The Engraver of the First Folio Portrait of William Shakespeare". Print Quarterly. VIII (1): 40–3. ISSN 0265-8305.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zinck, Arlette (2007). "Dating The Spiritual Warfare Broadsheet" (PDF). The Recorder: Newsletter of the International John Bunyan Society. International John Bunyan Society. 13: 3–4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Martin Droeshout. |