Markus Wolf

Markus Johannes Wolf (19 January 1923 – 9 November 2006) was head of the Main Directorate for Reconnaissance (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung), the foreign intelligence division of East Germany's Ministry for State Security (Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, abbreviated MfS, commonly known as the Stasi). He was the Stasi's number two for 34 years, which spanned most of the Cold War. He is often regarded as one of the most well known spymasters during the Cold War. In the West he was known as "the man without a face" due to his elusiveness.

Markus Wolf | |

|---|---|

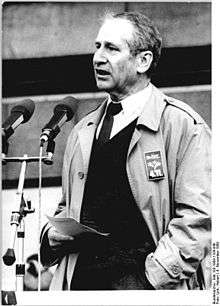

Wolf in 1989 | |

| Born | Markus Johannes Wolf 19 January 1923 Hechingen, Province of Hohenzollern, Weimar Germany |

| Died | 9 November 2006 (aged 83) |

| Burial place | Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Moscow Aviation Institute |

| Parent(s) | Friedrich Wolf (1888–1953) Else Wolf (1898–1973) |

| Awards | |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service branch | General Intelligence Administration (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung) |

| Service years | 1951–1986 |

| Rank | Colonel General |

| Signature | |

Life and career

Early life and education

Wolf was born 19 January 1923, in Hechingen, Province of Hohenzollern (now Baden-Württemberg), to a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother.[1][2] His father was the writer and physician Friedrich Wolf (1888–1953) and his mother was the teacher Else Wolf (née Dreibholz; 1898–1973).[3] He had one brother, the film director Konrad Wolf (1925–1982). His father was a member of the Communist Party of Germany, and after the anti-socialist and anti-Semitic Nazi Party gained power in 1933, Wolf emigrated to Moscow with his father, via Switzerland and France, because of their communist convictions and because Wolf's father was Jewish.[4][5][6]

During his exile, Wolf first attended the German Karl Liebknecht School and later a Russian school. In 1936, at the age of 13, he obtained Soviet identity documents.[7]

Career

After finishing school, Wolf entered the Moscow Institute of Airplane Engineering (Moscow Aviation Institute) in 1940, which was evacuated to Alma Ata after Nazi Germany's attack on the Soviet Union. There he was told to join the Comintern, where he among others was prepared for undercover work behind enemy lines. He also worked as a newsreader for German People's Radio after the dissolution of the Comintern, from 1943 until 1945.[8]

After the war he was sent to Berlin with the Ulbricht Group, led by Walter Ulbricht, to work as a journalist for a radio station in the Soviet Zone of occupation. He was among those journalists who observed the entire Nuremberg trials against the principal Nazi leaders. Between 1949 and 1951 Wolf worked at the East German embassy in the Soviet Union. That same year he joined the Ministry for State Security (Stasi).[8]

In December 1952, at the age of 29, Wolf was among the founding members of the foreign intelligence service within the Ministry for State Security.[8] As intelligence chief, he achieved great success in penetrating the government, political and business circles of West Germany with spies. The most notable individual in this regard was Günter Guillaume, who was secretary to and close friend of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, and whose exposure as an East German agent led to Brandt's resignation in 1974.[9]

For most of his career, Wolf was known as "the man without a face" due to his elusiveness. It was reported that Western agencies did not know what the East German spy chief looked like until 1978, when he was photographed by Säpo, Sweden's National Security Service, during a visit to Stockholm, Sweden. An East German defector, Werner Stiller, then identified Wolf to West German counter-intelligence as the man in the picture.[10] It has also been suggested that elements within the CIA had identified him by 1959 from photographs of attendees at the Nuremberg trials.[11]

Retirement

He retired in 1986 with the rank of Generaloberst, being succeeded by Werner Grossmann as head of the East German foreign intelligence service. He continued the work of his late brother Konrad in writing the story of their upbringing in Moscow in the 1930s. The book Troika came out on the same day in East and West Germany.

During the Peaceful Revolution, Wolf distanced himself from the hardline position taken by Erich Honecker, favouring reform. [12] He spoke at the November 1989 Alexanderplatz demonstration, where he was booed during his speech. The dissident Bärbel Bohley would later say:

When I saw that his hands were trembling because the people were booing I said to Jens Reich: We can go now, now it is all over. The revolution is irreversible."[13]

In September 1990, shortly before German reunification, Wolf fled the country, and sought political asylum in Russia and Austria. When denied, he returned to Germany where he was arrested by German police. Wolf claimed to have refused an offer of a large amount of money, a new identity with plastic surgery to change his features, and a home in California from the Central Intelligence Agency to defect to the United States.[2]

In 1993, he was convicted of treason by the Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf and sentenced to six years' imprisonment.[14] This was later quashed by the German supreme court, because West Germany was a separate country at the time.[15] In 1997, he was convicted of unlawful detention, coercion, and bodily harm, and was given a suspended sentence of two years' imprisonment.[16] He was additionally sentenced to three days' imprisonment for refusing to testify against Paul Gerhard Flämig when the former West German (SPD) politician was accused in 1993 of atomic espionage.[17] Wolf said that Flämig was not the agent that he had mentioned in his memoirs.

Markus Wolf died in his sleep at his Berlin home on 9 November 2006.[18]

Cultural impact

John le Carré's fictional spymaster Karla, a Russian, who appears in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, The Honourable Schoolboy, and Smiley's People was believed by some readers to be modeled on Wolf.[19] However, the writer has repeatedly denied it, and did so once again when interviewed on the occasion of Wolf's death.[20] Le Carré has also stated that it is "sheer nonsense" to claim that Wolf was the inspiration for the character Fiedler in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Although Fiedler is a German Jew who spent World War II in exile and then gained a senior position in East Germany's Intelligence Service, Carré said he had no idea who Markus Wolf was at the time of the writing of the book. He added that he considered Wolf to be the moral equivalent of Albert Speer.[21] He maintained that a character's code name Wolf in an early draft of the book was a coincidence and that the name came from the brand of his lawn mower.[22] He renamed the character after being told that there was an actual Wolf in East German intelligence.[23]

Conversely, Wolf stated that The Spy Who Came In From the Cold was the only book he read for a period in the early 1960s, and was surprised how accurately it presented the reality within the East German security services. He wondered if le Carré had had special information about the situation within the Ministry of State Security.[22]

Wolf appears as a character in Frederick Forsyth's novel The Deceiver. In the section entitled "Pride and Extreme Prejudice", a KGB officer liaises with East German intelligence while tracking down a British agent in East Germany. Forsyth also mentions Wolf in his earlier novel The Fourth Protocol, describing him, and the East German intelligence service as a whole, as masters of the false flag recruitment technique.

References

- Melman, Yossi (27 October 2004). "After East Germany Fell, I Considered Escaping to Israel'". Haaretz. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Wise, David (13 July 1997). "Spy vs. Spy". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Becker, Bodo (4 June 2018). "Else Wolf – zum 120. Geburtstag einer engagierten Mitbürgerin". Unser Lehnitz (in German). Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "Obituary: Markus Wolf". The Times. London. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- Axelrod, Toby (24 November 2006). "E. German spymaster Markus Wolf examined Jewish roots in later years". The Jewish News of Northern California. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Emerson, Steven (12 August 1990). "Where Have All His Spies Gone?". The New York Times.

- Müller-Enbergs, Helmut. "Wolf, Markus". Mfs-Lexikon (in German). Der Bundesbeauftragte für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Campbell, Kenneth J. (2011). "Markus Wolf: One of History's Most Effective Intelligence Chiefs". American Intelligence Journal. 29 (1): 148–157. JSTOR 26201932.

- Adams, Jefferson (15 September 2014). Strategic Intelligence in the Cold War and Beyond. Routledge. pp. 58–63. ISBN 9781317637684.

- Gieseke, Jens (1 January 2014). The History of the Stasi: East Germany's Secret Police, 1945-1990. Berghahn Books. p. 155. ISBN 9781782382553.

- "Markus Wolf BIO". Ovovideo.com. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Landler, Mark (10 November 2006). "Markus Wolf, German Spy, Dies at 83". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Steingart, Gabor; Ulrich Schwarz (7 November 1994). "Wir waren abgedriftet" (in German). Der Spiegel. pp. 40A. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

German: Als ich sah, daß seine Hände zitterten, weil die Leute gepfiffen haben, da sagte ich zu Jens Reich: So, jetzt können wir gehen, jetzt ist alles gelaufen. Die Revolution ist unumkehrbar.

- Vogel, Steve (7 December 1993). "East German Spymaster Found Guilty of Treason". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "'Man with no face' defiant in latest trial". The Irish Times. 8 January 1997. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Czuczka, Tony (27 May 1997). "Legendary East German spy chief gets suspended sentence". Associated Press. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "Markus Wolf". The Independent. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Smee, Jess (10 November 2006). "Markus Wolf, spy chief dubbed The Man Without a Face, dies at 83". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- "Obituary: Markus Wolf". BBC News Online. 9 November 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- "Obituary: Markus Wolf". The New York Times. 9 November 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- Plimpton, George (2004). "Lies Don't Last with Age". In Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph; Baughman, Judith (eds.). Conversations with John le Carré. University Press of Mississippi. p. 161. ISBN 9781578066698.

- Garton Ash, Timothy (26 June 1997). "The Imperfect Spy". The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504.(subscription required)

- Hoffman, Tod (2001). Le Carre's Landscape. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 143. ISBN 9780773569645.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Markus Wolf. |

Bibliography

- Wolf, Markus (with Anne McElvoy); Memoirs of a Spymaster; Pimlico; ISBN 0-7126-6655-9; (paperback 1997). Also published under the title Man without a face: the memoirs of a spymaster (Jonathan Cape, 1997). Wolf wrote six books between 1989 and 2002 but this is the only one translated into English.

- Dany Kuchel wrote in 2011, The Sword and the Shield, a story of the Stasi in France.