Marie Robinson Wright

Marie Robinson Wright (May 4, 1853 – February 1, 1914) was an American travel writer. She was elected member of learned societies in various parts of the world; and served as a special delegate or representative to international expositions. It was, however, as an observer and especially as a writer, that Wright gained her fame. Her books were written about Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Peru, and Mexico. These volumes were generous octavos, well illustrated, and filled with facts gathered chiefly from authoritative sources or confirmed by her own observations. They ran through more than one edition, and were esteemed in the countries they described.[1] She was a contemporary of Nellie Bly.[2]

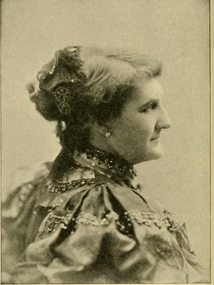

Marie Robinson Wright | |

|---|---|

.jpg) "A woman of the century" | |

| Born | Marie Louise Robinson May 4, 1853 Junius, New York, U.S. |

| Died | February 1, 1914 (aged 60) Liberty, New York |

| Occupation | travel writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | College Temple, Newnan |

| Spouse | Hinton P. Wright

( m. 1870; div. 1886) |

| Children | 2 |

Early years and education

Marie Louise Robinson was born in Newnan, Georgia, May 4, 1853. Her father, John Evans Robinson, was a wealthy planter. She was descended from the Evans family of Wales, of which Sir George Evans was the head.[3] Her father owned several plantations and hundreds of slaves. Her mother was Sarah Ramey Robinson, of Monroe County, Georgia.[4] She had at least four siblings, John E. Robinson, Emmie Robinson, Mrs. A. B. Cates, and Mrs. George H. Carmichael.[2]

Wright was reared in luxury,[5] and was educated at College Temple, Newnan.[4]

Career

In 1870, at the age of sixteen, she ran away and married Hinton P. Wright (1849–1892). Mr. Wright was the son of a prominent lawyer, Judge W. F. Wright, who was distinguished for his scholarly attainments.[5] In the previous year, Hinton Wright, in a boyish quarrel, inflicted injuries upon her brother which caused his death, and her parents disinherited her on the occasion of her marriage.[4]

Being bright and ambitious, she studied law with her husband, and sat by his side when he passed his final examination for the bar. They had two children, a daughter and a son.[6] The ravages of the Civl War devastated the State of Georgia so that neither husband nor father had any property left.[5] They divorced around 1886.

After the death of Mr. Wright in 1892, she found herself compelled to earn a living for herself and her children.[6] Wright went to the office of the magazine called the Sunny South, with a proposition that met the wants of the publishers. She asked for the privileges of traveling and soliciting subscriptions. Doubtless she had literary aspirations, but she knew that the business end of the magazine offered her a much quicker opportunity. She was engaged at once, and for two or three years, made a good living for herself and children, and materially increased the circulation of the periodical.[7]

So successful was Wright that a chance came from this work to go on to the New York World, not as a reporter or editorial writer, but to travel through the Southern cities and write them up for the daily paper. This work was even more successful. Her special line was descriptive writing and articles on new sections of the country. As special correspondent of the New York World in that department, she traveled from the British Provinces to Mexico in 1891. One of her noteworthy achievements during 1892 was her descriptive article of eight pages in the New York World on Mexico, supplemented by an illustrated souvenir of that country,[6] for which the Mexican government paid the paper the sum of US$20,000, in gold. It was the highest price ever paid for a newspaper article in its day.[8]

At the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, she was again given an opportunity to distinguish herself by getting the illustrated edition of the Fair, again making several thousand dollars.[7]

.png)

"But why should I go on making enormous sums of money for other people?" she asked herself. "Have I not now sufficient ability and experience to stand alone?"[7] She decided to try, and in 1895 with her daughter, Ida Dent Wright, for her sole companion, she went again to Mexico. Secretary of Foreign Affairs Ignacio Mariscal and President Porfirio Díaz were already her warm admirers, and it was to them she went with her plans. Both these executives furnished her with letters to every governor in Mexico, and the President ordered, not only a military escort wherever needed, but that special trains and steamboat facilities should be given her throughout the country. Then she spent a year in thoroughly inspecting and studying the country. Besides thousands of miles of railway and steamboat traveling, Wright and her daughter went nearly 900 miles (1,400 km) in mountain regions, on mules, attended by military escort, and penetrating regions where none but indigenous women had been seen previously. The result of her experiences was put in a large, illustrated book on Mexico, which was the most comprehensive and beautiful book on Mexico ever written in any language, and which was ordered in advance by 8,000 Mexican officials.[7]

In addition to this, or as a result of her success, Wright was invited to Costa Rica to prepare a similar book for the government.[9] As the years passed, she three times crossed South America, making a record trip over the Andes in 1904.[1]

Wright was a member of several press clubs and literary societies. She was sent to Paris as commissioner from the Georgia to the exposition, having been appointed by Governor John Brown Gordon, of Georgia. She served as vice-president for Georgia of the National Woman's Press Association.[4] While she was absorbed in her regular work, she occasionally contributed to other papers and magazines.[6]

Personal life

Wright made her home in New York City.[6] She died February 1, 1914, in Liberty, New York.[2]

References

- The Union 1914, p. 370.

- "Marie Robinson Wright obit". Newspapers.com. Atlanta Constitution. 3 February 1914.

- Willard & Livermore 1893, p. 804.

- White 1892, p. 231.

- Willard, Winslow & White 1897, p. 330.

- Willard & Livermore 1893, p. 805.

- Willard, Winslow & White 1897, p. 331.

- Demorest 1894, p. 541.

- Willard, Winslow & White 1897, p. 332.

Attribution

Demorest, W. J. (1894). Demorest's Family Magazine. 31 (Public domain ed.). W. J. Demorest.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) }}