Maria Reiche

Maria Reiche (15 May 1903 – 8 June 1998) was a German-born Peruvian mathematician, archaeologist, and technical translator. She is known for her research into the Nazca Lines, which she first saw in 1941[1] together with American historian Paul Kosok. Known as the "Lady of the Lines", Reiche made the documentation, preservation and public dissemination of the Nazca Lines her life's work.[1]

Maria Reiche | |

|---|---|

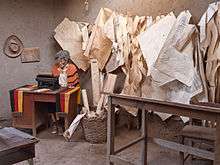

Maria Reiche in 1986 | |

| Born | 15 May 1903 |

| Died | 8 June 1998 (aged 95) |

| Alma mater | Dresden Technical University |

| Known for | Nazca Lines |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Archaeology |

She was widely recognized as the curator of the lines and lived nearby to protect them. She received recognition as Doctor Honoris Causa by the National University of San Marcos and the Universidad Nacional de Ingenieria in Lima. Reiche helped gain national and international attention for the Nazca Lines; Peru established protection, and they were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994.[2]

Following her death, her former home in Nazca was adapted as a museum, the Museo Maria Reiche. She is honored as the namesake of Maria Reiche Neuman Airport in Nazca, and of some fifty schools and other institutions in Peru. The 115th anniversary of her birth was commemorated with a Google Doodle in May 2018.[3][4][5]

Early life and education

.jpeg)

Maria Reiche was born in Dresden on 15 May 1903. She studied mathematics, astronomy, geography and foreign languages at the Dresden Technical University.[6] She learned to speak five languages.[1]

In 1932 as a young woman, she went to Peru to work as a governess and tutor for the children of the German consul in Cusco. In 1934, while still in Cusco, she accidentally stabbed herself with a cactus and lost a finger to gangrene.

In 1939, she became a teacher in Lima and also worked on scientific translations.[1] When World War II broke out that year, Reiche stayed in Peru. The next year she met American Paul Kosok, who was researching ancient irrigation systems in the country. She assisted him with making arrangements in the country, including a flight in 1941 by which she first saw the lines and figures of Nazca from the air.[1][7] They collaborated for years on further studies of these earthworks, trying to determine how they were made and, with more difficulty, for what purpose.

Nazca lines

In 1940, Reiche became an assistant to Paul Kosok, an American historian from Long Island University in Brooklyn, New York, who was studying ancient irrigation systems in Peru.[1]

In June 1941 Kosok noticed lines in the desert that converged at the point of the winter solstice in the Southern Hemisphere. Together he and Reiche began to map and assess the lines for their relation to astronomical events. Later Reiche found lines converging at the summer solstice and developed the theory that the lines formed a large-scale celestial calendar.[8] Around 1946, Reiche began to map the figures represented by the Nazca Lines and determined there were 18 different kinds of animals and birds.

After Kosok left in 1948, after his second study period in Peru, Reiche continued the work and mapped the area. She used her background as a mathematician to analyze how the Nazca may have created such huge-scale figures. She found these to have a mathematical precision that was highly sophisticated. Reiche theorized that the builders of the lines used them as a sun calendar and an observatory for astronomical cycles.[1]

Because the lines can be best seen from above, she persuaded the Peruvian Air Force to help her make aerial photographic surveys. She worked alone from her home in Nazca. Reiche published her theories in the book The Mystery on the Desert (1949, reprint 1968). She believed that the large drawing of a giant monkey represented the constellation now called Ursa Major (Great Bear).[8] Her book had a mixed response from scholars. Eventually scholars concluded that the lines were not chiefly for astronomical purposes, but Reiche's and Kosok's work had brought scholarly attention to the great resource. Some researchers believe that the lines were made as part of worship and religious ceremonies related to the "calling of water from the gods."[9]

Reiche used the profits from the book to campaign for preservation of the Nazca desert and to hire guards for the property and assistants for her work. Wanting to preserve the Nazca Lines from encroaching traffic, after one figure was cut through by the Pan American Highway government development, Reiche spent considerable money in the effort to lobby and educate officials and the public about the lines. After paying for private security, she convinced the government to restrict public access to the area. She sponsored construction of a tower near the highway so that visitors could have an overview of the lines to appreciate them without damaging them. Reiche contributed to the lines becoming a World Heritage site in 1994.[8]

In 1977, Reiche became a founding member of South American Explorers, a non-profit travel, scientific and educational organization. She was on the organization's advisory board and was interviewed for the South American Explorer on the lines' significance and importance.[10]

Personal life

Reiche's partner was Amy Meredith, who helped her in her work.[11]

Reiche's health deteriorated as she aged. She used a wheelchair, suffered from skin ailments, and lost her sight. In her later years, she also suffered from Parkinson's disease. At the age of 90 she published ''Contributions to Geometry and Astronomy in Ancient Peru''. Maria Reiche died of ovarian cancer on 8 June 1998,[8] in an Air Force Hospital in Lima. Reiche was buried with her sister near Nazca with official honors. A street and school in Nazca are named for her.

References

- Jr, Robert McG Thomas (15 June 1998). "Maria Reiche, 95, Keeper of an Ancient Peruvian Puzzle, Dies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Lines and Geoglyphs of Nasca and Palpa". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Smith, Kiona N. "Tuesday's Google Doodle Celebrates Nazca Line Archaeologist Maria Reiche". Forbes. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Today's Google Doodle celebrates the scientist who studied the mysterious desert lines of Peru". The Verge. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Maria Reiche's 115th Birthday". Google Doodles Archive. 15 May 2018. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Indianer-Welt: Nazca - Biographie: Maria Reiche". www.indianer-welt.de. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- "Maria and the Stars of Nazca". www.nazcaresources.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- "Who was the German governess obsessed with the mystery of Peru's Nazca Lines?". The Independent. 15 May 2018. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "The Nazca Lines", Peru Cultural Society. Archived from the original on 2012-01-28. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- "Bean Sprouts New Theory" (PDF). Retrieved 16 February 2013. South American Explorer, January 1983

- "FemBio - Frauen-Biographieforschung: Maria Reiche". www.fembio.org. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maria Reiche. |

- Asociación Maria Reiche, website, non-profit for conservation and preservation of the Lines and Figures of Nasca

- Association "Dr. Maria Reiche – Lines and Figures of the Nasca culture in Peru", University of Applies Sciences, Dresden

- Homepage Maria Reiche

- Zetzsche, Viola and Schulze, Dietrich: Biography of Maria Reiche, Picture Book of the Desert – Maria Reiche and the Ground Designs of Nasca, Mitteldeutscher Verlag Halle, September 2005, ISBN 3-89812-298-0

- Maria Reiche at Find a Grave

- Maria Reiche. Detailed chronology (with literature from Peru)

- "Maria Reiche and the Stars of Nazca", Anita Jepson-Gilbert, Nazca Resources.