Maria Barbella

Maria Barbella (born October 24, 1868[2] – after 1902) was an Italian-born American woman. Erroneously known as Maria Barberi at the time, she was the second woman sentenced to die in the electric chair. She was convicted of killing her lover in 1895; however, the ruling was overturned in 1896 and she was freed. Her trial became a cause célèbre in the late 19th century.

Maria Barbella | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 24, 1868 |

| Died | After 1902 |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Other names | Maria Barberi[1] |

| Known for | Second woman sentenced to die in the electric chair |

Life

Maria Barbella was born in Ferrandina, Basilicata, Italy. Her family immigrated to Mulberry Bend, New York, in 1892. After living in the United States for nearly a year, Maria Barbella met Domenico Cataldo, who was from the same region of Italy. She worked in a factory and every day she would pass by Cataldo’s shoeshine booth. They spent much time together but these meetings were kept a secret from Michele Barbella, Maria's overprotective father. Michele found out about Domenico, and he forbade Maria from ever seeing or speaking to him again. Domenico continued to pursue Maria until she finally gave in and agreed to meet with him again.

One day Cataldo took her to a boarding house, where he allegedly drugged her with the drink he bought her, and raped her. Maria demanded that he marry her. Cataldo showed her a savings book with a $400 deposit and promised he would. Maria continued to live with him at the boarding house. However, Cataldo continued to put the marriage off for several months. In fact he was already married to a woman in Italy, with whom he had children.

Barbella was devastated when Cataldo told her that he was returning to Italy and was ending the relationship. Barbella then told her mother about the situation. Her mother confronted Cataldo and insisted he marry Barbella but he said the only way he would do that was if they paid him $200. In New York City on April 26, 1895, at approximately 9:30 am, Domenico Cataldo was playing cards in a saloon on East 13th Street, and had planned to board a ship leaving for Italy that afternoon. Barbella entered the bar and there was a brief exchange. "Only a pig can marry you!" were his last words. Barbella produced a straight razor and slashed his neck so swiftly Cataldo had no chance to scream. He staggered out the door, clutching his throat with both hands, knocking Barbella over, spraying blood everywhere. Finally, as he reached Avenue A, he lurched off the curb and fell twitching into the gutter, where he died.[3]

Trial

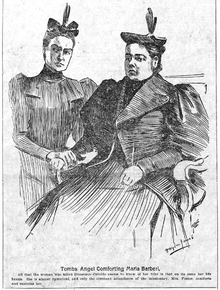

Barbella was arrested and put in The New York Halls of Justice and House of Detention (otherwise known as "The Tombs")[4] for 2.5 months. Her appointed attorneys were Amos Evans and Henry Sedgwick. The trial began on July 11. This case stirred up controversy because Italians felt that the verdict was unjust since there were no Italians in the jury. At the time of the trial, Barbella was unable to speak or understand English.[1] She admitted everything: how she slit his throat and how he ran after her, but couldn’t reach her and had dropped dead. The jury was shown to have felt sympathy for her case; however, according to Recorder Goff, "The verdict was in accordance with the facts, and no other verdict could, in view of the evidence, have been considered."[1] The jury declared Barbella guilty and she was sent to Sing Sing prison where she was sentenced to death by electric chair occurring on August 19, 1895.[1] She was the second woman sentenced to be executed by electric chair (after serial killer Lizzie Halliday's commuted 1894 conviction).[5][1][6]

Second trial and release

Many complained to Governor Levi Morton about how the situation was handled, but it seemed nothing could be done. She was granted an appeal on the basis of the judge's jury instructions, which explicitly argued in favor of conviction.[7] On November 16, 1896, she was given a second trial. This time, counsel presented a much more sympathetic case: that she was a rape victim whose experience exacerbated her preexisting epilepsy. She allegedly suffered a seizure and lost her reason.[8] She was found not guilty. After her release from prison, she again made headlines for rescuing a neighbor who had accidentally set herself on fire. Barbella grabbed a blanket and beat the fire out with her hands.[9] Barbella married an Italian immigrant named Francesco Bruno on November 4, 1897. In 1899, she had a son named Frederick. In 1902, she was living with her parents, and her husband had returned to Italy and remarried. Nothing is known of her life after this time.

In popular culture

"Illicit and Lethal" - episode about Maria Barbella's life from the documentary Deadly Women, originally aired on Discovery Channel in 2017.

The November 1st, 2019 episode of the podcast The Memory Palace tells her story.[10]

References

- "Maria Barbella to Die" (PDF). New York Times. July 19, 1895. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- http://www.essortment.com/all/mariabarbella_rluk.htm%5B%5D

- "Maria Barbella's Second Trial" (PDF). New York Times. November 17, 1896. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- A Tale of The Tombs, www.correctionhistory.org. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- James D. Livingston, Arsenic and Clam Chowder: Murder in Gilded Age New York, SUNY Press - 2012, pages 64-65

- Lisa Varisco Daigle, Questions of responsibility: the New York press presents the murderess, 1870-1900, Georgia State University - 2002, page 156

- Barbella, Maria, Appellant. "The People of the State of New York, Respondent, V. Marie Barberi, Appellant." Court of Appeals of New York 149 N.Y. 256; 43 N.E. 635 (1896)

- "Experts Talk of Epilepsy." New York Times Dec. 8 1896: 16.

- "Maria Barberi in Role of Heroine." New York Journal December 31, 1896, p. 1

- "The Story of Maria Barberi". The Memory Palace. November 1, 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Fleischer, Lawrence. "Maria Barbella: The Unwritten Law and the Code of Honor in Gilded Age New York." From In Our Own Voices: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Italian and Italian American Women. Boca Raton, Florida: Bordighera Press, 2003, pgs. 67-74.

- Messina, Elizabeth G. "Women and Capital Punishment: The Trials of Maria Barbella." From In Our Own Voices: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Italian and Italian American Women. Boca Raton, Florida: Bordighera Press, 2003, pgs. 53-65.

- Pucci, Idanna. The Trials of Maria Barbella. New York: Vintage, 1996.