Marguerite Bellanger

Marguerite Bellanger (10 June 1838 - 23 November 1886) was a French stage actress and courtesan. She was a celebrity of Second Empire France and known for her relationship with Napoleon III of France. She was often caricatured in contemporary press and is considered to be the model for Émile Zola's Nana. A candy is also named after her. She was reputedly the most universally loathed of Napoleon III's mistresses, though perhaps his favorite[1][2]. She outlived Napoleon's deposal in 1870 and died in 1886 aged 48.

Marguerite Bellanger | |

|---|---|

Marguerite Bellanger around 1870 by Eugène Disdéri | |

| Born | Julie Justine Marine Lebœuf June 10, 1838 |

| Died | November 23, 1886 (aged 48) |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Actress , courtesan. |

| Known for | Mistress of Napoleon III |

Early life

Marguerite Bellanger was born Julie Justine Marine Lebœuf[3] on 10 June 1838 in Saint-Lambert-des-Levées, Maine-et-Loire to François Lebœuf and Julie Hanot. Born into poverty,[4] she began working as a laundress in Saumur at the age of 15.

After an affair with a lieutenant opened her eyes to the wider world,[5] she became an acrobat and trick rider in a provincial circus,[6] she travelled to Paris where she made her debut as an actress at the theater La Tour d'Auvergne,[7] under the name of Marguerite Bellanger (the surname of an uncle).[5]

Although her acting talent was limited, she was cunning. She became one of the most sought-after cocottes of all Paris. She led a princely lifestyle, and the climax of her gallant life took place in the years 1862–1866. She is reported to have said: "It is very nice Paris, but it is only habitable in the beautiful districts ... In the others, there are too many poor!" according to Le Rappel of 16 April 1871. Author and playwright, Ludovic Halévy, is reputed to have said that Bellanger had the "daintiest feet in Paris".[8]

Her celebrity status was such that she became a figure in the literary and artistic world. Zola quoted her as a friend of Nana.[9]

She was photographed in man's suit: to do this, she had asked permission from the police department.[10]

Bellanger was a favourite model of the sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, who represented her as an allegory of spring in an elegant terracotta bust in which is today in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris.[11]

In a painting by Édouard Manet in 1863, Olympia, the artist endeavoured to evoke an odalisque, who receives a bouquet of flowers brought by her maid. According to Phyllis A. Floyd's study, The Puzzle of Olympia, he gave the painting the features of Marguerite Bellanger.[12]

Mistress of Napoleon III

In June 1863, while on a carriage ride in Saint-Cloud Park, Emperor Napoleon III spotted Bellanger sheltering from the rain beneath a tree. Napoleon was bewitched by his new encounter.

Marguerite Bellanger become the mistress of the Emperor. Soon, with the knowledge of all including the Empress Eugénie, she followed him on private and official trips.[13]

Amongst his numerous presents, the Emperor gave her two houses, one at 57 rue des Vignes, Passy,[14] the other at Saint-Cloud, in the park of Montretout, which had a back door to the gardens of the castle.

In February 1864, Marguerite Bellanger gave birth to a son; whom she named Charles Jules Auguste François Marie Leboeuf.

After the birth, Bellanger retired for a while to rue de Launay in Villebernier[15] and received a pension. In November 1864, the Emperor offered "Margot" the castle of Villeneuve-sous-Dammartin, near Meaux. The Emperor also gave the child a boarding house and the castle of Mouchy, in the Oise, which he had bought very discreetly some time before. Bellanger became usufructuary of the property.

Always seductive, Bellanger still attracted men when she settled in Villeneuve-sous-Dammartin at the end of 1864. Among her lovers were General de Lignières and, according to some sources, Léon Gambetta.

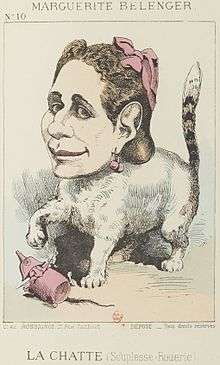

She was the subject of caricatures and gossip. Paul Hadol, in his series of caricatures on the "Imperial Menagerie", portrayed her as a cat.[16]

Her affair with the emperor continued during the Franco-Prussian War, and even during his captivity in Westphalia. In 1873, when the emperor died in exile in England, she travelled to England to mourn her 'dear lord'.[17]

Later life

At the fall of the Empire, she again traveled to England and married William Louis Kulbach, a British army officer.[18] The presence of the couple William Kulbach and Marguerite Bellanger is recorded in Monchy-Saint-Éloi (Oise), France in the census of 1872.[19] Bellanger gave her age as 30 years, whereas according to the data in her biography, she was 33 or 34.

She lived the rest of her life as a member of the upper class, devoting herself to charity and good works.

Death and legacy

Marguerite Bellanger died at the age of 48 on 23 November 1886 after contracting a cold during a walk in the park of the castle at Villeneuve-sous-Dammartin. According to the declaration of death, her husband lived in Pau. The religious ceremony took place on 27 November at the church of Saint-Pierre-de-Chaillot and she was interred in Montparnasse Cemetery.

Her brother Jules, who served as a gardener, benefited from her estate. He built a beautiful house in Brain-sur-Allonnes, which is now the town hall.

Her only son, Charles Leboeuf, made a career as an officer and died without issue on 11 December 1941. He was buried with his mother.

Cultural Heritage

Filmography

Bellanger's character appears in Christian-Jaque's film Nana (1955), in which her character is performed by Nicole Riche.

Gastronomy

Marguerite Bellanger has been associated with a chocolate specialty: a praline was created to honour her. A chocolatier from Saumur designed, with the help of archivists of the city of Saumur, a specialty The Marguerite.

The coat of arms of Marguerite Bellanger is reproduced on the chocolates: a daisy with a heart of silver and gold petals. The praline "with four spices" (cloves, cinnamon, pepper and nutmeg) echos the qualities that the second Empire sought to give her: a varnish of heart, a spicy charm and an imperial dress.

References

- Markham 1975, p. 201.

- Loliee & Ivimy 1907.

- The Bookman 1909, p. 372.

- "Marguerite Bellanger". Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Friedrich 1993, p. 157.

- Loliée & O'Donnell 1910, p. 279.

- Ridley 1980, p. 493.

- Kracauer 1938, p. 220.

- Nana , novel of Emile Zola published in 1880, the ninth in the series Les Rougon-Macquart

- Houbre 2006, p. 184.

- Janoray & Champion 2003, p. 24.

- Floyd, Phylis A. "Phylis A. Floyd on The Puzzle of Olympia". 19thc-artworldwide.org. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Bernard Vassor, La femme « homme d'affaires »

- Aubry 1931, p. 151.

- Curry 1871, p. 162.

- Lambert 1971, p. 38.

- Frerejean, Alain (July 2006). "Margot la Rigoleuse et "son" cher Empereur". www.historia.fr (in French). Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "LA PROSTITUTION". saumur-jadis.pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Archives départementales de l'Oise. Recensement de population 1872. Cote 6 Mp 474 (Microfilm 2_Mi_A68_409) page 5/11 (consulté en ligne le 13 décembre 2011)

Autobiographies

- Bellanger, Marguerite (1882). Confessions de Marguerite Bellanger. Mémoires anecdotiques (in French). librairie populaire.

- Bellanger, Marguerite (1900). Les Amours de Napoléon III, mémoires de Marguerite Bellanger, sa maîtresse (in French). P. Fort.

Bibliography

- Aubry, Octave (1931). Eugénie, Empress of the French. J.B. Lippincott.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curry, T (1871). The secret documents of the Second empire, found in the Tuileries and ministries in Paris after the flight of the empress, tr. by T. Curry. W Tweedie.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedrich, Otto (1993). Olympia: Paris in the Age of Manet. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671864118.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Houbre, Gabrielle (2006). Le livre des courtisanes: archives secrètes de la police des moeurs, 1861-1876 (in French). Tallandier. ISBN 9782847343441.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Janoray, Charles; Champion, Jean-Loup (2003). A Golden Age of French Sculpture 1850-1900: Exhibition, May 5-May 30, 2003. Charles Janoray LLC.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kracauer, Siegfried (1938). Orpheus in Paris: Offenbach and the Paris of His Time. Knopf.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambert, Susan (1971). The Franco-Prussian War and the Commune in caricature, 1870-71: catalogue of a collection of prints in the possession of the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Victoria and Albert Museum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Loliee, Frederic; Ivimy, Alice M (1907). Women of the second empire: chronicles of the court of Napoleon III. John Lane.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Loliée, Frédéric; O'Donnell, Bryan (1910). The Gilded Beauties of the Second Empire. Brentano's.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Markham, Felix Maurice Hippisley (1975). The Bonapartes. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 9780297769286.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ridley, Jasper Godwin (1980). Napoleon III and Eugénie. Viking Press. ISBN 9780670504282.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Bookman. 2. Dodd, Mead and Co. 1909.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marguerite Bellanger. |