Manuel Francisco Pavón Aycinena

Manuel Francisco Pavón Aycinena (1798 - 19 April 1855) was an influential conservative Guatemalan politician during the regime of General Rafael Carrera. Leader of the Aycinena family, was in charge of setting up the government executive branch during this period, holding practically all of the Cabinet offices over the years.[1] The liberal historians portray him as a villain in a despotic and tyrannical government headed by illiterate Raca Carraca - Rafael Carrera; [2] [3][4] However, research conducted between 1980 and 2010 has shown a more objective biography of both Pavón and Rafael Carrera and show that it was in fact Carrera who had the reins of the Conservative government.[5] [6] [7]

Manuel Francisco Pavón Aycinena | |

|---|---|

| |

Government Advisor Guatemala | |

| In office 1844–1848 | |

| President | Rafael Carrera |

Secretary of State[Note 1] Guatemala | |

| In office November 6, 1852 – April 19, 1855 | |

| President | Rafael Carrera |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1798 Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción |

| Died | April 19, 1855 |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Occupation | politician |

Biography

Pavón Aycinena attended the Pontifical University of San Carlos Borromeo and participated in the war against Francisco Morazán and his liberal forces under the command of the Governor of Guatemala, Mariano de Aycinena y Piñol as Lieutenant Colonel in the army. After Aycinena's defeat, he was banished by Morazan with another one hundred families belonging to the Aycinena clan, going into exile to Panama and then to the United States. He returned to Guatemala in 1837 when rebel general Rafael Carrera had asserted his authority in the state and managed to become one of his top aides and government ministers [8]

Role in Rafael Carrera's government

Executive branch

Pavón Aycinena held all the executive branch offices during Carrera's term as President; it is considered that Pavón Aycinena is responsible for the current setup of those branches.[9]

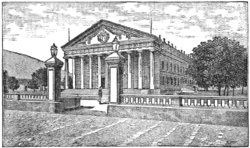

Carrera Theater

Later on, the site became a market and on 6 Augusto 1832, then Guatemalan Governor, Dr. Mariano Galvez issued a decree to build a theater in the middle of Plaza Vieja. But the political situation of the country, with the continuous uprisings and civil wars between liberal and conservatives and a peasant revolt led by Rafael Carrera took down Galvez, who could not accomplish his infrastructure ambitions for the city.[11]

In 1852, Juan Matheu and Pavón Aycinena presented Rafael Carrera with a plan to build a majestic National Theater, that would be called Carrera Theater in his honor. Once approved, Carrera commissioned Matheu himself and Miguel Ruiz de Santisteban to build the theater. Initially it was in charge of engineer Miguel Rivera Maestre, but he quit after a few months and was replaced by German expert José Beckers, who built the Greek façades and added a lobby. This was the first monumental building ever built in the Republican era of Guatemala,[11] given that in the 1850s the country finally was enjoying some peace and prosperity.[12]

Appleton's Guide to México and Guatemala of 1884 describes the theater as follows: «In the middle of the square is the Theater, similar in size and elegance to any of the rest of Spanish America. Lines of orange trees and other nice trees of brilliant flowers and delicious fragrances surround the building while the statues and fountains placed at certain intervals enhance even more the beauty of the place.[13]

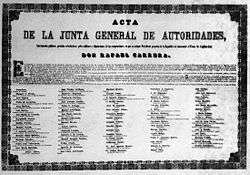

Carrera declared President for life

After the Battle of La Arada, on 22 October 1851 presidente Mariano Paredes resigned; then the National Assembly named Carrera as his successor, being inaugurated as president on 6 November 1851 after having had the senators modify the Constitution to fit his needs.[14] By then, Pavón Aycinena was suffering of intestine problems, which worsened with the beginning of spring each year, leaving him exhausted.[15] In fact, on 5 May 1853 he became so ill that was put in hospice, but he managed to survive and work towards making sure that president Carrera was named president for life.[15] Finally, on 25 October 1854, at the initiative of Pavón Aycinena, Carrera was declared "supreme and perpetual leader of the nation" for life, with the power to choose his successor; as such, Carrera served as President of Guatemala until he died on April 14, 1865. [15]

Death

In February 1855, Pavón went to Escuintla to sped the season, but his health took a turn for the worse; the then returned to Guatemala City on 17 March, where in spite of the care of his doctor, Dr. Abella, his sickness progressed to a point that on 15 April a priest was called to comfort Pavón in his last moments.[15] From that moment on, his confessor, —father Luis Amoros, S.J.— did not leave his side, and neither did his wife and siblings; he put his business in order and name his cousins Pedro de Aycinena —then Secretary of Interior— and Luis Batres Juarros —then Presidential Advisor— in charge in his inheritance.[15]

Pavón Aycinena was the first of the main allied of general Carrera to die; he died on 19 April 1855 at 5 a.m. in his home, and surround by his relatives and important ecclesiastic figures.[15] General Carrera was in Chimaltenango, but from there sent instructions to take care of Pavón's funeral on 20 April.[15] His funeral service took place in the Cathedral, where the main figures of the clerical and political circles of the country were in attendance. Later on, he was buried in La Merced Church.[16]

On 7 May 1855, upon returning from his business trip to Los Altos, Carrera commanded that a portrait of Pavón Aycinena were placed in the main room of the Presidential Palace and, taking in consideration the long list of Pavón's accomplishment, he granted his widow a lifelong pension equivalent to half of her deceased husband,[16] —the largest pension ever granted in Guatemala up to that point.[17]

See also

- Francisco Morazán

- History of Guatemala

- History of Central America

Notes and references

References

- Woodward 1993, p. 256.

- Montúfar & Salazar 1892.

- Rosa 1974.

- Hernández de León 1930.

- Woodward 1993.

- Woodward 2002.

- González Davison 2008.

- González Davison 2008, p. 6-154.

- Gobierno de Guatemala 1855.

- Conkling 1884.

- Guateantaño & 17 October 2011

- González Davison 2008, p. 432.

- Conkling 1884, p. 343.

- Hernández de León 1930, p. 97.

- La Gaceta de Guatemala 1855, p. 19

- La Gaceta de Guatemala 1855, p. 20

- Gobierno de Guatemala 1855, p. 1.

Bibliography

- Conkling, Alfred R. (1884). Appleton's guide to Mexico, including a chapter on Guatemala, and a complete English-Spanish vocabulary. Nueva York: D. Appleton and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chandler, David L (1978). "The house of Aycinena". Revista de la Universidad de Costa Rica (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gobierno de Guatemala (1855). Nota fúnebre de Manuel Francisco Pavón Aycinena (in Spanish). Guatemala.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- González Davison, Fernando (2008). La montaña infinita;Carrera, caudillo de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Artemis y Edinter. ISBN 84-89452-81-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guateantaño (17 October 2011). "Parques y plazas antiguas de Guatemala". Guatepalabras Blogspot. Guatemala. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hernández de León, Federico (1959). "El capítulo de las efemérides". Diario La Hora (in Spanish). Guatemala.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hernández de León, Federico (1930). El libro de las efemérides (in Spanish). Tomo III. Guatemala: Tipografía Sánchez y de Guise.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- La Gaceta de Guatemala (30 June 1828). "Parte no oficial". La Gaceta de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Imprenta de La Unión (6).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- — (1855). "Noticia biográfica del señor D. Manuel Francisco Pavón, Consejero de Estado y Ministro de lo Interior del gobierno de la República de Guatemala". La Gaceta de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Imprenta La Paz, Palacio de Gobierno de Guatemala. VII (58–62).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martínez Peláez, Severo (1988). Racismo y Análisis Histórico de la Definición del Indio Guatemalteco (in Spanish). Guatemala: Editorial Universitaria.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martínez Peláez, Severo (1990). La patria del criollo; ensayo de interpretación de la realidad colonial guatemalteca (in Spanish). México: Ediciones en Marcha.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milla y Vidaurre, José (1980). Cuadros de Costumbres. Textos Modernos (in Spanish). Guatemala: Escolar Piedra Santa.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Molina Moreira, Marco Antonio (1979). Manuel Francisco Pavón Aycinena, constructor del sistema político del Régimen de los Treinta Años (PDF). Tesis (in Spanish). Guatemala: Escuela de Historia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Montúfar, Lorenzo; Salazar, Ramón A. (1892). El centenario del general Francisco Morazán (in Spanish). Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosa, Ramón (1974). Historia del Benemérito Gral. Don Francisco Morazán, ex Presidente de la República de Centroamérica (in Spanish). Honduras: Ministerio de Educación Pública, Ediciones Técnicas.

- Stephens, John Lloyd; Catherwood, Frederick (1854). Incidents of travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan. London, England: Arthur Hall, Virtue and Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weaver, Frederic S. (March 1999). "Reform and (Counter) Revolution in Post-Independence Guatemala: Liberalism, Conservatism, and Postmodern Controversies". Latin American Perspectives. 26 (2): 129–158.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodward, Ralph Lee, Jr. (2002). "Rafael Carrera y la creación de la República de Guatemala, 1821–1871". Serie monográfica (in Spanish). CIRMA y Plumsock Mesoamerican Studies (12). ISBN 0-910443-19-X. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2015-01-27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodward, Ralph Lee, Jr. (1993). Rafael Carrera and the Emergence of the Republic of Guatemala, 1821-1871 (Online edition). Athens, Georgia EE.UU.: University of Georgia Press. Retrieved 28 December 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Notes

- Pavón Aycinena served also as War, Justice, Foreign Affairs and Ecclesiastical Affairs secretary under Rafael Carrera and Mariano Paredes.