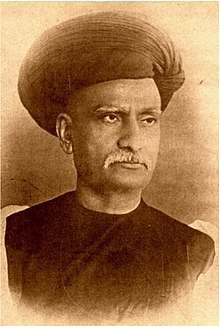

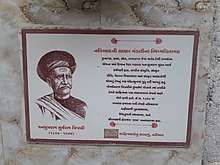

Mansukhram Tripathi

Mansukhram Suryaram Tripathi (pronounced [mənsukʰɾɑːm suɾjəɾɑːm t̪ɾipɑːʈʰiː]; 1840–1907) was a Gujarati essayist, biographer, and thinker from British India. He led a conservative school of Gujarati writers who advocated avoiding the use of foreign words in writing and speaking, and promoted the use of Sanskrit or Sanskritised words. He was a cousin of the Gujarati writer Govardhanram Tripathi.

Mansukhram Tripathi | |

|---|---|

Mansukhram Tripathi | |

| Born | Mansukhram Suryaram Tripathi 23 May 1840 Nadiad, British India |

| Died | 30 May 1907 (aged 67) Nadiad, British India |

| Occupation | Essayist, biographer, and thinker |

| Language | Gujarati |

| Nationality | British Indian |

| Home town | Nadiad |

| Spouse | Dahilakshmi |

| Relatives | Govardhanram Tripathi (younger cousin) |

Biography

Tripathi was born into a Vadnagara Nagar Brahmin family[1] on 23 May 1840 in Nadiad in the British Indian state of Gujarat to his father, Suryaram, and mother, Umedkunwar. His father died when he was eight.[2] He received his secondary and college education in Kheda and Ahmedabad.[3] In 1861, he joined Elphinstone College, but left due to an eye-problem.[2] Later he made a career as a stock trader.[1] He died on 30 May 1907 in Nadiad.[2] Gujarati writer Govardhanram Tripathi was his younger cousin.[4]

Tripathi was associated with several literary associations in Gujarat. He was one of the founder members of Farbus Gujarati Sabha and was a member of Buddhi Vardhak Sabha. In 1870, he founded Dharma Sabha in Ahmedabad and became editor of its organ Dharmaprakash. He founded the Dahilakshmi Library in Nadiad in memory of his wife Dahilakshmi.[2] He was appointed as a fellow of Mumbai University, and was appointed a justice of the peace.[1] In 1866–67 (Vikram Samvat 1923), Gokulji Zala, a dewan (a senior government official) of Junagadh state, heard a lecture by Tripathi at Bombay, and was impressed. Later Zala appointed Tripathi as one of agents of Junagadh state at Bombay.[1]

Works

A collection of his essays was published as Astodaya (Rise and Fall). They are descriptive, narrative and reflective in nature. Since he wanted to use only words of Sanskrit origin, the language of his essays is highly loaded.[3]

Tripathi wrote two biographies: Forbes Jivan Charitra (1869), which presents the career and achievements of Alexander Kinloch Forbes, a colonial administrator in British India. The second biography, Sujna Gokulji Jhala Jivancharitra (1900), tells the life story of Gokulji Jhala, the dewan of Junagadh state, and presents an account of Kathiawadi politics and society between 1860 and 1880. Since Gokulji was a Vedantist, the book also contains a detailed chapter on Shankaracharya, one of the founders of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy.[5]

In collaboration with Ranchhodbhai Udayram Dave, he wrote Shakespeare Katha Samaj, which presents abridged versions of Shakespeare's plays.[3]

Conservatism

Tripathi led a conservative school of Gujarati writers.[6] He was one of the earliest and strongest proponents of a highly Sanskritized Gujarati language. He insisted on removing all words of Persian, Arabic or English origin from Gujarati and replacing them with Sanskrit words. As a result of this Ramanbhai Neelkanth, a liberal intellectual and a proponent of Western culture, targeted him in his novel Bhadrambhadra in which the protagonist insists on using highly Sanskritized language.[4]

Tripathi also tried to popularize the Devanagari script by writing several works in it, but he was unsuccessful.[6] His style of Sanskritised Gujarati was followed by his younger cousin Govardhanram Tripathi in his epic novel Sarswatichandra. Manilal Dwivedi (fl. 1882–1898), a Gujarati writer, was also a follower of Tripathi.[7]

See also

References

- Vaidyashastri, Manishankar Govindaji (1902). ગુજરાતી ગ્રંથકારો અને ગ્રંથો [Who's Who in Gujarati Literature] (in Gujarati). 1. pp. 32–42.

- Joshi, Ramanlal (1997). Thaker, Dhirubhai (ed.). ગુજરાતી વિશ્વકોશ [Gujarati Encyclopedia] (in Gujarati). VIII. Ahmedabad: Gujarati Vishwakosh Trust. pp. 765–766. OCLC 164810484.

- Lal, Mohan, ed. (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. p. 4395. ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3.

- Shukla, Sonal (1995). "Gujarati Cultural Revivalism". In Patel, Sujata (ed.). Bombay: Mosaic of Modern Culture. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-563689-5.

- V. K. Chavda (1982). Modern Gujarat. Ahmedabad: New Order Book Company. p. 48. OCLC 9477811.

- Diwanji, Prahlad C. (1932–1933). "NĀGARA APABHRAṀŚA AND NĀGARĪ SCRIPT: A REVIEW". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 14 (3/4): 268. JSTOR 41682433.

- Shukla, Sonal (26 October 1991). "Cultivating Minds: 19th Century Gujarati Women's Journals". Economic and Political Weekly. 26 (43): 64. eISSN 2349-8846. ISSN 0012-9976 – via EPW.