Epic of Manas

The Epic of Manas (Kyrgyz: Манас дастаны, ماناس دستانی, Kazakh: Манас дастаны, Manas dastany, Azerbaijani: Manas dastanı, Turkish: Manas Destanı) is a traditional epic poem dating to the 18th century but claimed by the Kyrgyz people to be much older. The plot of Manas revolves around a series of events that coincide with the history of the region in the 17th century, primarily the interaction of the Turkic-speaking people from the mountains to the south of the Dasht-i Qipchaq and the Oirat Mongols from the bordering area of Jungaria.

Manas monument in Bishkek | |

| Original title | Манас дастаны |

|---|---|

| Written | 18th century |

| Language | Kyrgyz language |

| Subject(s) | A series of events that coincide with the history of the region in the 17th century, primarily the interaction of the Turkic-speaking people from the mountains to the south of the Dasht-i Qipchaq and the Oirat Mongols from the bordering area of Jungaria |

| Genre(s) | Epic poem |

| Lines | Approximately 500,000 |

The government of Kyrgyzstan celebrated the 1,000th anniversary of Manas in 1995. The eponymous hero of Manas and his Oirat enemy Joloy were first found written in a Persian manuscript dated to 1792-3.[1] In one of its dozens of iterations, the epic poem consists of approximately 500,000 lines.

Narrative

The epic tells the story of Manas, his descendants, and their exploits against various foes. The Epic of Manas is divided into three books. The first is entitled "Manas", the second episode describes the deeds of his son Semetei, and the third of his grandson Seitek. The epic begins with the destruction and difficulties caused by the invasion of the Oirats. Jakyp reaches maturity in this time as the owner of many herds without a single heir. His prayers are eventually answered, and on the day of his son's birth, he dedicates a colt, Toruchaar, born the same day to his son's service. The son is unique among his peers for his strength, mischief, and generosity. The Oirat learn of this young warrior and warn their leader. A plan is hatched to capture the young Manas. They fail in this task, and Manas is able to rally his people and is eventually elected and proclaimed as khan.

Manas expands his reach to include that of the Uyghurs of Raviganjn on the southern border of Jungaria. One of the defeated Uighur rulers gives his daughter to Manas in marriage. At this point, the Kyrgyz people chose, with Manas' help, to return from the Altai mountains to their "ancestral lands" in the mountains of modern-day Kyrgyzstan. Manas begins his successful campaigns against his neighbors accompanied by his forty companions. Manas turns eventually to face the Afghan people to the south in battle, where after defeat the Afghans enter into an alliance with Manas. Manas then comes into a relationship with the people of mā warā' an-nār through marriage to the daughter of the ruler of Bukhara.

The epic continues in various forms, depending on the publication and whim of the manaschi, or reciter of the epic.

History

The epic poem's age is unknowable, as it was transmitted orally without being recorded. However, historians have doubted the age claimed for it since the turn of the 20th century. The primary reason is that the events portrayed occurred in the 16th and 17th centuries. Central Asian historian V. V. Bartol'd referred to Manas as an "absurd gallimaufry of pseudo-history,"[1] and Hatto remarks that Manas was

"compiled to glorify the Sufi sheikhs of Shirkent and Kasan ... [and] circumstances make it highly probable that... [Manas] is a late eighteenth-century interpolation."[2]

Changes were made in the delivery and textual representation of Manas in the 1920s and 1930s to represent the creation of the Kyrgyz nationality, particularly the replacement of the tribal background of Manas. In the 19th century versions, Manas is the leader of the Nogay people, while in versions dating after 1920, Manas is a Kyrgyz and a leader of the Kyrgyz.[3]

Attempts have been made to connect modern Kyrgyz with the Yenisei Kirghiz, today claimed by Kyrgyzstan to be the ancestors of modern Kyrgyz. Kazakh ethnographer and historian Shokan Shinghisuly Walikhanuli was unable to find evidence of folk-memory during his extended research in 19th-century Kyrgyzstan (then part of the expanding Russian empire) nor has any been found since.[4]

While Kyrgyz historians consider it to be the longest epic poem in history,[5] the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata and the Tibetan Epic of King Gesar are both longer.[6] The distinction is in number of verses. Manas has more verses, though they are much shorter.

Recitation

Manas is the classic centerpiece of Kyrgyz literature, and parts of it are often recited at Kyrgyz festivities by specialists in the epic, called Manasçı (Kyrgyz: Манасчы). Manasçıs tell the tale in a melodic chant unaccompanied by musical instruments.

Kyrgyzstan has many Manasçıs. Narrators who know all three episodes of the epic (the tales of Manas, of his son Semetey and of his grandson Seytek) can acquire the status of Great Manasçı. Great Manasçıs of the 20th century are Sagımbay Orozbakov, Sayakbay Karalaev, Şaabay Azizov (pictured), Kaba Atabekov, Seydene Moldokova and Yusup Mamay. Contemporary Manasçıs include Rysbek Jumabayev, who has performed at the British Library,[7] Urkaş Mambetaliev, the Manasçı of the Bishkek Philharmonic (also travels through Europe), and Talantaalı Bakçiyev, who combines recitation with critical study.[8] Adil Jumaturdu has provided "A comparative study of performers of the Manas epic." [9]

There are more than 65 written versions of parts of the epic. An English translation of the version of Sagımbay Orozbakov by Walter May was published in 1995, in commemoration of the presumed 1000th anniversary of Manas' birth, and re-issued in two volumes in 2004. Arthur Thomas Hatto has made English translations of the Manas tales recorded by Shokan Valikhanov and Vasily Radlov in the 19th century.

Legacy

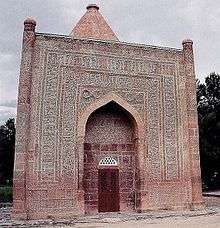

Manas is said to have been buried in the Ala-Too mountains in Talas Province, in northwestern Kyrgyzstan. A mausoleum some 40 km east of the town of Talas is believed to house his remains and is a popular destination for Kyrgyz travellers. Traditional Kyrgyz horsemanship games are held there every summer since 1995. An inscription on the mausoleum states, however, that it is dedicated to "...the most famous of women, Kenizek-Khatun, the daughter of the emir Abuka". Legend has it that Kanikey, Manas' widow, ordered this inscription in an effort to confuse her husband's enemies and prevent a defiling of his grave. The name of the building is "Manastin Khumbuzu" or "The Dome of Manas", and the date of its erection is unknown. There is a museum dedicated to Manas and his legend nearby the tomb.

The reception of the poem in the USSR was problematic. Politician and government official Kasym Tynystanov tried to get the poem published in 1925, but this was prevented by the growing influence of Stalinism. The first extract of the poem to be published in the USSR appeared in Moscow in 1946, and efforts to nominate the poem for the Stalin Prize in 1946 were unsuccessful. Ideologist Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin's "propagandist in chief", prevented this, calling the poem an example of "bourgeois cosmopolitanism". The struggle continued inside Kyrgyzstan, with different newspapers and authors taking different sides; one of its supporters was Tugelbay Sydykbekov. By 1952 the poem was called anti-Soviet and anti-Chinese and condemned as pan-Islamic. Chinghiz Aitmatov, in the 1980s, picked up the cause for the poem again, and in 1985 finally a statue for the hero was erected.[10]

Influence

- Liz Williams' Nine Layers of Sky (2003) writes a modern day account of Manas as a nemesis of the Bogatyr Ilya Muromets.

- University of Manas - the name of university in the city of Bishkek.

- The main international airport of Kyrgyzstan, Manas International Airport in Bishkek, was named after the epic.

- A minor planet, 3349 Manas was discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1979.[11]

- The highest award in Kyrgyzstan is the Order of Manas

- Manas - opera, composed by Abdylas Maldybaev

Translations

Manas has been translated into 20 languages. The Uzbek poet Mirtemir translated the poem into Uzbek.[12]

See also

References

- Tagirdzhanov, A. T. 1960. "Sobranie istorij". Majmu at-tavarikh, Leningrad.

- Akiner, Shirin & Sims-Williams, Nicholas. Languages and Scripts of Central Asia. 1997, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. p. 99

- kiner, Shirin & Sims-Williams, Nicholas. Languages and Scripts of Central Asia. 1997, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. p. 104

- 1980. 'Kirghiz. Mid-nineteenth century' in [Traditions of heroic and epic poetry I], edited by A. T. Hatto, London, 300-27.

- Урстанбеков Б.У., Чороев Т.К. Кыргыз тарыхы: Кыскача энциклопедиялык сөздүк: Мектеп окуучулары үчүн. – Ф.:Кыргы. Совет Энциклопедиясыныны Башкы Ред., 1990. 113 б. ISBN 5-89750-028-2

- Amartya Sen, The Argumentative Indian. Writings on Indian Culture, History and Identity, London: Penguin Books, 2005.

- Gullette, David (2010). The Genealogical Construction of the Kyrgyz Republic: Kinship, State and ‘Tribalism’. Folkestone: Global Oriental. p. 153.

- Plumtree, James (2019). "A Kyrgyz Singer Of Tales: Formulas in Three Performances of the Birth of Manas by Talantaaly Bakchiev". Доклады Национальной академии наук Кыргызской Республики: 125–133.

- Jumaturdu, Adil (2016). "A Comparative Study of Performers of the Manas Epic". The Journal of American Folklore. 129 (513): 288–296. doi:10.5406/jamerfolk.129.513.0288.

- Laruelle, Marlene (2015). "Kyrgyzstan's Nationhood: From a Monopoly of Production to a Plural Market". In Laruelle, Marlene; Engvall, Johan (eds.). Kyrgyzstan beyond "Democracy Island" and "Failing State": Social and Political Changes in a Post-Soviet Society. Lexington Books. pp. 165–84. ISBN 9781498515177.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2013). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (3 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 439. ISBN 9783662066157.

- "Mirtemir (In Uzbek)". Ziyouz. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

External literature

- Manas. Translated by Walter May. Rarity, Bishkek, 2004. ISBN 9967-424-17-6

- Levin, Theodore. Where the Rivers and Mountains Sing: sound, music, and nomadism in Tuva and beyond. Section "The Spirit of Manas", pp. 188–198. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006

- Manas 1000. Theses of the international scientific symposium devoted to the 'Manas' epos Millenial [sic] Anniversary. Bishkek, 1995.

- S. Mussayev. The Epos Manas. Bishkek, 1994

- Traditions of Heroic and Epic Poetry (2 vols.), under the general editorship of A. T. Hatto, The Modern Humanities Research Association, London, 1980.

- The Memorial Feast for Kokotoy-Khan, A. T. Hatto, 1977, Oxford University Press

- The Manas of Wilhelm Radloff, A. T. Hatto, 1990, Otto Harrassowitz

- Spirited Performance. The Manas Epic and Society in Kyrgyzstan. N. van der Heide, Amsterdam, 2008.

- Ying, Lang. 2001. The Bard Jusup Mamay. Oral Tradition. 16(2): 222-239. Web access

External links

- at the Manas University, Kyrgyz Turkish Manas University

- Manas at the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative, Texas Tech University

- In-depth site on Manas with translated sections of the epic

- Manas at China.org.cn

- "Manas: The Kyrgyz Odysseys, Moses, and Washington", article examining the place of Manas in Kyrgyz mythology and national identity

- Epos "Manas" Text of epic poems "Manas", "Semetey" and "Seytek", others kyrgyz epic poems.

- Video of Manas Epic recitations