Mammoth Mountain

Mammoth Mountain is a lava dome complex west of the town of Mammoth Lakes, California, in the Inyo National Forest of Madera and Mono Counties.[3] It is home to a large ski area on the Mono County side.

| Mammoth Mountain | |

|---|---|

Mammoth Mountain from the south, with Ritter Range behind | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 11,053 ft (3,369 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 1,647 ft (502 m) [2] |

| Coordinates | 37°37′50″N 119°01′57″W [1] |

| Geography | |

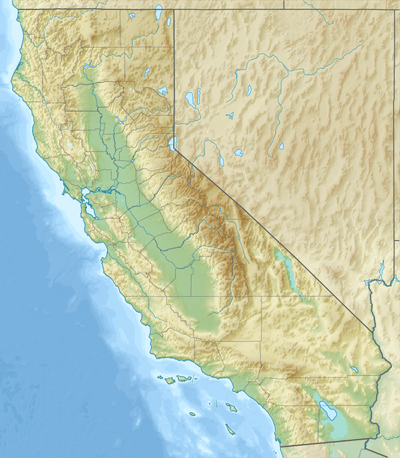

Mammoth Mountain  Mammoth Mountain Mammoth Mountain (the United States) | |

| Parent range | Sierra Nevada |

| Topo map | USGS Mammoth Mountain |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | About 50,000 to 200,000 years |

| Mountain type | Lava dome complex[3] |

| Last eruption | 1260 ± 40 years[3] |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Gondola[4] |

Mammoth Mountain was formed in a series of eruptions that ended 57,000 years ago. Mammoth still produces hazardous volcanic gases that kill trees and caused ski patroller fatalities in 2006.[5]

Geology

Mammoth Mountain is a lava dome complex in Mono County, California. It lies in the southwestern corner of the Long Valley Caldera[6] and consists of about 12 rhyodacite and dacite overlapping domes.[7] These domes formed in a long series of eruptions from 110,000 to 57,000 years ago, building a volcano that reaches 11,059 feet (3,371 m) in elevation.[8] During this time, massive dacite eruptions occurred roughly every 5000 years.[9] The volcano is still active with minor eruptions, the largest of which was a minor phreatic (steam) eruption 700 years ago.[3]

Mammoth Mountain also lies on the south end of the Mono-Inyo chain of volcanic craters.[10] The magma source for Mammoth Mountain is distinct from those of both the Long Valley Caldera and the Inyo Craters.[3][11][12] Mammoth Mountain is composed primarily of dacite and rhyolite,[13] part of which has been altered by hydrothermal activity from fumaroles (steam vents).[14]

Volcanic gas discharge

Mammoth is outgassing large amounts of carbon dioxide out of its south flank, near Horseshoe Lake, causing mazuku in that area. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the ground ranges from 20 to 90 percent CO2. Measurements of the total discharge of carbon dioxide gas at the Horseshoe Lake tree-kill area range from 50 to 150 short tons (45 to 140 t) per day. This high concentration causes trees to die in six regions that total about 170 acres (0.69 km2) in size (see photo).[15]

The tree-kills originally were attributed to a severe drought that affected California in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Another idea was that the kills were the result of a pathogen or other biological infestation. However, neither idea explained why all trees in the affected areas were killed regardless of age or health. Then, in March 1990, a U.S. Forest Service Ranger became ill with suffocation symptoms after being in a snow-covered cabin near Horseshoe Lake.[16]

Measurements around the lake found that restrooms and tents had a greater than 1% CO2 concentration (toxic) and a deadly 25% concentration of CO2 in a small cabin. CO2 concentrations of less than 1% are typical and healthy in most soils; however, soil concentrations of CO2 in the tree-kill areas ranged from 20% to 90%. This overabundance of CO2 was found to be the cause of the tree-kills because tree roots need to absorb O2 directly and the high CO2 level reduced available O2. Researchers also determined that Mammoth releases about 1,300 short tons (1,200 t) of CO2 every day. As of 2003, the concentration of carbon dioxide in soil gas at Mammoth Mountain is being monitored on a continuous, year-round basis at four sites—three at Horseshoe Lake and one near the base of Chair 19 at the ski area.[15]

The most likely sources of the CO2 are degassing of intruded magma and gas release from limestone-rich metasedimentary rocks that are heated by magmatic intrusions. The remarkable uniformity in chemical and isotopic composition of the CO2 and accompanying gases at different locations around Mammoth Mountain indicates that there may actually be a large reservoir of gas deep below the mountain from which gas escapes along faults to the surface.[15] Measurements of helium emissions support the theory that the gases emitted in the tree kill area have the same source as those discharged from Mammoth Mountain Fumarole.[12][17] There is evidence that the rate of CO2 discharge has been declining,[18] with emissions peaking in 1991.[19]

In April 2006, three members of the Mammoth Mountain Ski Area ski patrol died while on duty. All three died from suffocation by carbon dioxide when they fell into a fumarole on the slopes of the mountain.[20]

Recreational use

.jpg)

Mammoth Mountain is home to the Mammoth Mountain Ski Area, founded by Dave McCoy in 1953. Mammoth is a ski, snowboard, and snowmobile mountain during the winter months. Mammoth is the highest ski resort in California and is notable for the unusually large amount of snowfall it receives compared to other Eastern Sierra peaks—about 400" annually and about 300 out of 365 days of sunshine—due to its location in a low gap in the Sierra crest.[21] In the summer months the ski gondolas are used by mountain bikers and tourists who wish to get a summit view of Long Valley Caldera directly to the east and Sierra peaks to the west, south and north.[4] To the south of the mountain, there are a number of lakes that serve as tourist attractions in the summer.

References

- "706 702 2=Mammoth". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- "Mammoth Mountain, California". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- "Mammoth Mountain". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- Jones, Finn-Olaf (2008-02-29). "Mammoth Mountain Ski Area". Ski Guide. The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- Hymon, Steve; Covarrubias, Amanda (2006-04-09). "How Routine Turned to Tragedy at Mammoth". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- Martini, B.A.; Silver, E.A.; Potts, D.C.; Pickles, W.L. (July 2000). Geological and geobotanical studies of Long Valley Caldera, CA, USA utilizing new 5m hyperspectral imagery. Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2000. Proceedings. IGARSS 2000. IEEE 2000 International. 4. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. pp. 1376–1378. doi:10.1109/IGARSS.2000.857212.

- "Long Valley Caldera and Mono-Inyo Craters Volcanic Field, California". Volcano World. Archived from the original on 2008-01-14.

-

Lewicki, Jennifer L.; Birkholzer, Jens; Tsang, Chin-Fu (February 2006). "Natural and Industrial Analogues for Release of CO

2 from Storage Reservoirs: Identification of Features, Events, and Processes and Lessons Learned" (PDF). United States Department of Energy/Office of Scientific and Technical Information. Retrieved 2008-08-18. Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Harris, Stephen L. (2005). Fire Mountains of the West (3rd ed.). Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-511-2.

-

Hill, David P.; Bailey, Roy A.; Sorey, Michael L.; Hendley II, James W.; Stauffer, Peter H. (May 2000). "Living With a Restless Caldera—Long Valley, California – U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 108-96". Online Version 2.1. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-08-18. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hildreth, Wes (2004-09-14). "Volcanological perspectives on Long Valley, Mammoth Mountain, and Mono Craters: several contiguous but discrete systems". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. Elsevier B.V. 136 (3–4): 169–198. Bibcode:2004JVGR..136..169H. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2004.05.019.

- DePaolo, Don; Sorey, Mike; Evans, Bill; Farrar, Chris; Cook, Andrea; Hainsworth, Laura; Rogie, John. "Volcanic Hazards and CO2 Emissions: Mammoth Mountain Long Valley Caldera, California". Center for Isotope Geochemistry – Nobel Gas Isotope Geochemistry. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- "Geologic History of Long Valley Caldera and the Mono-Inyo Craters volcanic chain, California". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- Pease, Robert C. "Hydrothermal System of the Long Valley Caldera". Volcanoes of the Eastern Sierra Nevada: Geology and Natural Heritage of the Long Valley Caldera. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- "Carbon Dioxide and Helium Discharge from Mammoth Mountain". USGS Volcano Hazards Program Long Valley Observatory. USGS. 2001-12-27. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- Farrar, C.D.; Neil, J. M.; Howle, J. F. (1999). "Magmatic Carbon Dioxide Emissions at Mammoth Mountain, California". Water-Resources Investigations report 98-4217. USGS.

- "Helium Discharge at Mammoth Mountain Fumarole (MMF)". United States Geological Survey. 2003-07-30. Archived from the original on 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- Farrar, C.D.; Bergfeld, D. (December 2007). Magmatic Carbon Dioxide Emissions From Mammoth Mountain, California —- A Decreasing Trend From 1996 to 2007. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2007. American Geophysical Union. Bibcode:2007AGUFM.V21C0722F.

-

Sorey, Michael L.; Farrar, Christopher D.; Gerlach, Terrance M.; McGee, Kenneth A.; Evans, William C.; Colvard, Elizabeth M.; Hill, David P.; Bailey, Roy A.; Rogie, John D.; Hendley II, James W.; Stauffer, Peter H. (2007-07-09). "Invisible CO

2 Gas Killing Trees at Mammoth Mountain, California – U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 172-96". Online Version 2.0. USGS. Retrieved 2008-08-19. Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Covarrubias, Amanda; Doug Smith (2006-06-07). "3 Die in Mammoth Ski Patrol Accident". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- Burak, S.A.; R.E. Davis (2001). Preliminary evaluation of snow accumulation patterns based on storm type, Mammoth Mountain, California, 1996–2001 (PDF). Proc. Western Snow Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-30.

- Further reading

- Alt, David; Hyndman, Donald (2000). Roadside Geology of Northern and Central California. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-409-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |