Malting

Malting is a controlled germination that converts raw grain into malt. The malt is mainly used for brewing or whisky making, but can also be used to make malt vinegar or malt extract. Various grains are used for malting; the most common are barley, sorghum, wheat and rye. There are a number of different types of equipment that can be used to produce the malt. A traditional floor malting germinates the grains in a thin layer on a solid floor, and the grain is manually raked and turned to keep the grains loose and aerated. In a modern malt house the process is more automated, and the grain is germinated on a floor that is slotted to allow air to be forced through the grain bed. Large mechanical turners, e.g., Saladin boxes, keep the much thicker bed loose with higher productivity and better energy efficiency.

Intake

The grain is received at the malt house from the farmer. It is taken in from the field and cleaned (dressed) and dried if necessary to ensure the grain remains in the best condition to produce good malt.

The barley is tested to check for suitability for malting and to prevent dead or unfit barley from entering the process. Some of the typical quality checks include:

- Grain moisture

- Nitrogen content (total nitrogen)

- % of foreign matter

- Absence of fungal growth and metabolites

- Germinative capacity and germinative energy

- Water sensitivity

Drying

Barley received at the malt house with moisture of more than 13% must be dried before it can be safely stored without loss of germinative capacity (GC). The moisture is removed by circulating heated air (up to 50 °C) through the grain and can either be performed using dedicated grain driers or as a batch process using a kiln. High temperatures or over-drying will damage or kill the barley embryos and the grain will not germinate after steeping. The dry barley can safely be stored for up to 18 months without fungal growth or loss of grain vigour.

Cleaning

The aim of barley cleaning is to remove foreign matter (straw, chaff, dust and thin corns) found in the incoming grain, leaving only the grain most likely to produce a good malt. Magnets are used to remove metals from the grain, in turn reducing the possibility of sparks, which could lead to a dust explosion. Rotating and shaking sieves are used to remove unwanted foreign matter either larger (straw and un-threshed ears) or smaller (sand and thin corns) than the normal barley grain. During the sieving process an aspiration system removes the dust and chaff. De-stoners or shaking screens are used to separate small stones from the barley. The stones, which are more dense than the barley, move out the top of the machine and the cleaned barley exits at the bottom. Half corn separators may be used to remove broken kernels. Half kernels need to be removed as only the one half will germinate and produce enzymes. At the end of the cleaning process the grain is weighed to determine the cleaning losses (the difference between the weight of grain received and the weight of the grain after cleaning) and it is transferred to a silo for storage.

Storage

The barley must be safely stored to maintain the grain vigour for germination. Storage at a malt house is normally in vertical silos made of steel or concrete for ease of use; but may be in flat stores when large amounts of grain is to be stored. The grain is stored in a manner that protects it from moisture and pests. A typical silo will store between 5,000 and 20,000 tons of clean dry barley ready for malting.

During storage the temperature of the silo is measured and monitored over time as a temperature increase can indicate insect activity. Additional equipment may be used to keep the grain temperature below 18 °C to inhibit insect growth. Silos are normally fitted with a system for rotating grain from one silo to another to break-up hot spots within the grain. A fumigation system can be used to administer a fumigant (normally phosphine) to the silo.

Wet process

The wet process begins with steeping to get germination started and ends with kilning which removes the moisture and produces a stable final product.[1]

A batch of malt is known as a piece and a piece can be as large as 400 tons. Below a standardised base malt protocol is described:

Steeping

Steeping is the start of the active malting process, steep water is added to cover the grain and the grain moisture content increases from around 12% to between 40 and 45%. In a modern pneumatic malt house, the grain is alternatively submerged (wet stand) and then drained (an air rest) for two or three cycles to achieve the target grain moisture content and chit count.

Wet Stand When the grain is immersed in water (known as a wet stand), air is bubbled through the slurry of water and grain periodically. The aim of this aeration[2] is to keep the process aerobic to maximize barley growth. Other advantages of the rousing are to get good mixing, to loosen dirt and to even out hydrostatic pressures at the bottom of the steep vessels. (Air flow rate: 1.5m3/ton per hour)[3]

Air rest or dry stand. At the end of the wet stand the water is drained out and this is the start of the air rest. During the air rest, fans are run to supply fresh oxygen and to remove excess CO2 produced by grain respiration. The temperature of the air supplied is important as it shouldn't impact on the grain temperature during steeping (10 to 15 °C). The aeration requirements (cubic metres per ton per minute) are higher in the second and third air rests as the grain metabolic activity is higher. (Air flow rate: 300m3/ton per hour).[3]

At the end of steeping the grain is cast-out to germination. Cast-out may be done as a slurry during a wet stand or as moist grain during an air rest.

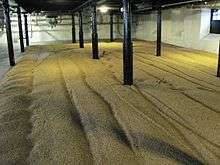

Germination

The aim of germination is to grow the barley grains. This allows the development of malt enzymes, and these enzymes modify the structure of the barley endosperm by breaking down the cell walls and the protein matrix. Germination produces a large amount of heat; if safety precautions are not taken the malt will burn.[4]

The enzymes produced during germination are needed to break down the starch for the brewer or distiller during the mashing process.

The grain bed is maintained at a constant temperature of between 10 and 16 °C by the constant supply of fresh humidified air and turners move through the grain bed to keep it loose to allow for sufficient air-flow.

Kilning

Kilning thus reduces the grain moisture content and stops the germination process.[5] In the first stage, the free drying stage the air temperatures are kept cool to dry the grain without causing the enzymes to denature.

As the grain dries it is possible to raise the air-on temperatures, (the second stage or the forced drying stage) to further dry the grain, the target malt moisture after kilning is around 5% by weight. During forced drying the relative humidity of the air coming off the bed drops and the maltster is able to use a portion of the warm air as return air.

During the last few hours of kilning the air on temperature is raised to above 80 °C (the curing stage) to break SMM down to DMS to reduce the DMS potential of the malt. DMS is an off flavour that tastes like sweetcorn in the final beer.

The high temperatures of kilning also produce the colour in the malt through the Maillard reaction.

Finally the kilned malt is cooled before the kiln is stripped (emptied).

Deculming

The rootlets of the malt (also known as culms) are removed from the malt soon after transfer from the kiln.

The removed culms are sold or processed as animal feed.[6]

The cleaned malt is stored in silos to be blended with similar malt pieces to produce larger homogenous batches of malt.

Malt cleaning

Finally the malt is cleaned prior to sale using sieves and aspiration to remove the dust, lumps and stones in the malt. Magnets are again used to remove any steel that might damage the mill rollers.

Further reading

- Dennis Edward Briggs, Malts and Malting Department of Biochemistry University of Birmingham, 787 p., Chapman & Hall, 1984

- Henry Stopes, Malt and Malting -An Historical Scientific and Practical Treatise, published in 1885

References

- "Malt Production". boortmalt.com. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Lewis, Michael J.; Young, Tom W. (2002). Brewing. Springer. pp. 168–171. ISBN 9780306472749.

- Briggs, Dennis E. (1998). Malts and Malting. Springer. pp. 369–389.

- "The Malting Process". brewconductor.com. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- "Kilning & Roasting". brewconductor.com. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Malt culms, malt sprouts, malt coombs". fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on December 29, 2012. Retrieved December 7, 2012.