Maria Malibran

Maria Felicia Malibran (24 March 1808 – 23 September 1836) was a Spanish singer who commonly sang both contralto and soprano parts, and was one of the best-known opera singers of the 19th century. Malibran was known for her stormy personality and dramatic intensity, becoming a legendary figure after her death at age 28. Contemporary accounts of her voice describe its range, power and flexibility as extraordinary.

Life and career

Malibran was born in Paris as María Felicitas García Sitches into a famous Spanish musical family. Her father, Manuel García, was a celebrated tenor much admired by Rossini, having created the role of Count Almaviva in his The Barber of Seville. García was also a composer and an influential vocal instructor, and he was her first voice teacher. He was described as inflexible and tyrannical; the lessons he gave his daughter became constant quarrels between two powerful egos.

Early career

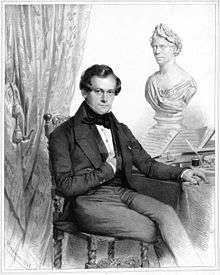

_par_F._Bouchot.jpg)

Malibran first appeared on stage in Naples with her father in Paër’s Agnese, when she was 8 years old. When she was 17, she was a singer in the choir of the King's Theatre in London. When prima donna Giuditta Pasta became indisposed, García suggested that his daughter take over in the role of Rosina in The Barber of Seville. The audience loved the young mezzo, and she continued to sing this role until the end of the season.

Later career

When the season closed, García immediately took his operatic troupe to New York. The troupe consisted primarily of the members of his family: Maria, her brother, Manuel, and their mother, Joaquina Sitchez, also called "la Briones". Maria's younger sister, Pauline, who would later become a famous singer in her own right under the name of Pauline Viardot, was then only four years old.

This was the first time that Italian opera was performed in New York. Over a period of nine months, Maria sang the lead roles in eight operas, two of which were written by her father. In New York, she met and hastily married a banker, Francois Eugene Malibran, who was 28 years her senior. It is thought that her father forced Maria to marry him in return for the banker's promise to give Manuel García 100,000 francs. However, according to other accounts, she married simply to escape her tyrannical father. A few months after the wedding, her husband declared bankruptcy, and Maria was forced to support him through her performances. After a year, she left Malibran and returned to Europe.

In Europe, Malibran sang the title role at the premiere of Donizetti's Maria Stuarda. The opera was based on Friedrich Schiller's play Mary Stuart, and as it portrayed Mary, Queen of Scots in a sympathetic light, censors demanded textual amendments, which Malibran often ignored. The Library of the Royal Conservatory of Brussels conserves a series of interesting coloured costume projects[1] for this play, created by Malibran, revealing her unsuspected drawing talent.

Malibran became romantically involved with the Belgian violinist, Charles Auguste de Bériot. The pair lived together as a common-law couple for six years and a child was born to them in 1833 (the piano pedagogue Charles-Wilfrid de Bériot), before Maria obtained an annulment of her marriage to Malibran. Felix Mendelssohn wrote an aria accompanied by a solo violin especially for the couple. Malibran sang at the Paris Opera among other major opera houses. In Paris, she met and performed with Michael Balfe.

Last years and death

In 1834, Malibran moved to England and began to perform in London. In late May 1836, she starred in The Maid of Artois, written for her by Balfe. Earlier that year she had returned to Milan to sing the title role in the premiere of Vaccai's Giovanna Gray. In July 1836, Malibran fell from her horse and suffered injuries from which she never recovered.[2][3] She refused to see a physician and continued to perform. In September 1836 Malibran was in Manchester participating in a music festival at the collegiate church and Theatre Royal on Fountain Street. She collapsed on stage while performing encores at the theatre, but insisted on performing in the church the following morning and died after a week of agony, attended by her private physician. Her body was temporarily buried in the church after a public funeral before being moved to a mausoleum in Laeken Cemetery, near Brussels in Belgium.[4] The Library of The Royal Conservatory of Brussels conserves, amongst others, the death mask, the poignant 4-page funerary report of Dr. Belluomini as well as the authorisation of the Manchester ecclesiastical authority to have Malibran's body transferred to Brussels (Maria Malibran fund, B-Bc; FC-2-MM-006 sq.).

Roles and vocal style

Malibran is most closely associated with the operas of Rossini. The composer extolled her virtues:

- Ah! That wonderful creature! With her disconcerting musical genius she surpassed all who sought to emulate her, and with her superior mind, her breadth of knowledge and unimaginable fieriness of temperament she outshone all other women I have known....[5]

Among other operas, she sang the title role in Tancredi and in Otello, in which it appears that she sang both the roles of Desdemona and of Otello.[6] Other appearances included those in Il turco in Italia, La Cenerentola, and Semiramide (both Arsace and the title role).[6]

She also sang in Giacomo Meyerbeer's Il crociato in Egitto in Paris in September 1825, an opera which Rossini, as director of the Théâtre-Italien, introduced to the French capital and "which launched Meyerbeer's European reputation".[7] Malibran enjoyed great success in Bellini's operas Norma, La sonnambula and I Capuleti e i Montecchi (as Romeo). She also sang the Romeo role in two other then-famous operas: Giulietta e Romeo by Zingarelli and Giulietta e Romeo by Vaccai. Bellini wrote a new version of his I puritani to adapt it to her mezzo-soprano voice and even promised to write a new opera especially for her, but he died before he was able to do so.

Malibran's tessitura (comfortable vocal range) was remarkably wide, from E♭ below middle C to high C and D,[8] which allowed her easily to sing roles for contralto as well as high soprano. Her contemporaries admired Malibran's emotional intensity on stage. Rossini, Donizetti, Chopin, Mendelssohn and Liszt were among her fans. The painter Eugène Delacroix however, accused her of lacking refinement and class and of trying to "appeal to the masses who have no artistic taste." Describing her voice and technique, French critic Castil-Blaze wrote, "Malibran's voice was vibrant, full of brightness and vigor. Without ever losing her flattering timbre, this velvet tone that has given her so much seduction in tender and passionate arias. [...] Vivacity, accuracy, ascending chromatics runs, arpeggios, vocal lines dazzling with strength, grace or coquetry, she possessed all that the art can acquire."[9]

Legacy

Maria Malibran fund

The Library of the Royal Conservatory of Brussels possesses an important collection of scores, documents and objects from the diva, assembled in the Maria Malibran fund.

Film

Several films depict the life of Maria Malibran:

- Maria Malibran (1943) directed by Italian director Guido Brignone and starring Moldovan-born Austrian soprano and actress Maria Cebotari.[10]

- La Malibran (1944) directed by French director Sacha Guitry starring Géori Boué, celebrated singer of the Opéra de Paris.[10]

- Malibran's Song (1951) a Spanish film directed by Luis Escobar Kirkpatrick

- The Death of Maria Malibran (1971) directed by German filmmaker Werner Schroeter. It starred Candy Darling.[10]

In other media

In 1982, soprano Joan Sutherland did a recital tour called "Malibran" in order to revive Malibran's memory, singing pages from the singer's favourites in Venice.[11]

The mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli dedicated her 2007 album Maria to the music composed for Malibran and her most famous roles, as well as an extensive tour and DVD concert dedicated to La Malibran. In 2008 Decca released a recording Bellini's La Sonnambula with Cecilia Bartoli in the lead role using many cadenzas that la Malibran herself used and which restored the tessitura of the role to the high mezzo-soprano range (as Giuditta Pasta and Maria Malibran had sung it).

Letitia Elizabeth Landon includes a poetic tribute, in miniature, in The English Bijou Almanack, 1837.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

She appears as a character in a poem by William McGonagall.[12]

Mark Twain's daughter Susy Clemens, dying of spinal meningitis, wrote a final delirious prose poem addressed to Malibran, whom she regarded as a kind of patron saint: "Tell her to say God bless the shadows as I bless the light."[13]

References

Notes

- Maria Malibran, La Réforme du Théâtre, (Library of the Royal Conservatory of Brussels, B-Bc, Maria Malibran fund, FC-2-MM-073).

- Teresa Radomski, "Manuel García (1805–1906): A bicentenary reflection", Australian Voice, Vol. 11, 2005, (p. 25–41). Accessed 28 August 2010

- Mainardi, Zanchin, Paladin and Maggioni,Acute-on-chronic subdural hematoma: the death of the famous XIX century soprano Maria Malibran -- a study of the sources. Neurological Science 2018 Oct;39(10):1819-1821. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3494-z. Epub 2018 Jul 10. PMID 29987434.

- Shanks p. 14.

- Giachino Rossini, in Bartoli 2007, p. 8

- Letter from Carlo Severini to Éduard Robert (Co-Director of the Théâtre-Italien), 1829: "She will do three jobs for us...", in Bartoli, Maria, p. 10

- Servadio 2003, (p. 127)

- Merlin, Memoires and Letters of Mme Malibran, Philadelphia, Carey and Hart, 1840

- Saint Bris

- IMBD page on the film

- Sutherland on YouTube

- McGonagall, William. "Little Pierre's Song".

- Ron Powers, Mark Twain. Simon and Schuster, 2005.

Cited sources

- Ashbrook, William (1982), Donizetti and His Operas, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052123526X ISBN 0-521-23526-X

- Bartoli, Cecilia (2007), "Genius, Scandal and Death: Maria — Singer and Diva", in Maria. Decca Music Group, with accompanying CD and DVD.

- Merlin, Countess de, (1840) Memoirs and letters of madame Malibran, Vol 2. Philadelphia: Carey and Hart.

- Riggs, Geoffrey S. (2009), The Assoluta Voice in Opera, 1797 to 1847. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co Inc. ISBN 9780786440771 ISBN 0-7864-1401-4

- Saint Bris, Gonzague (2009), La Malibran, Belfond. ISBN 978-2-7144-4542-1

- Servadio, Gaia (2003), Rossini, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003. ISBN 0-7867-1195-7

- Shanks, Andrew (2010), Manchester Cathedral: The Old Church of the World's First Great Industrial City, Scala Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85759-658-8

Other sources

- Bushnell, Howard (1980), Maria Malibran: A Biography of the Singer, Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0271002220 ISBN 0-271-00222-0

- FitzLyon, April (1987), Maria Malibran: Diva of the Romantic Age, London: Souvenir Press Ltd. ISBN 0285650300 ISBN 0-285-65030-0

- Languine, Clément (1911), La Malibran, Paris

- Nathan, I. (1846), Life of Mme. Maria Malibran. London

- Pougin, Arthur (1911 & 2010), Maria Malibran, Histoire d'une Cantatrice. Paris: 1911; English trans., London, 1911. Kessinger Publishing, US, 2010 ISBN 9781160188388 (print on demand)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maria Malibran. |

- Information about Malibran's performance in The Maid of Artois, one of her last roles