Malaysian Cantonese

Malaysian Cantonese (Chinese: 馬來西亞廣東話; Cantonese Yale: Máhlòihsāia Gwóngdūng wá) is a local variety of Cantonese spoken in Malaysia. It is the lingua franca among Chinese throughout much of the central portion of Peninsular Malaysia, being spoken in the capital Kuala Lumpur, southern Perak, Pahang, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan, it is also widely understood to varying degrees by many Chinese throughout the country, regardless of their ancestral dialect.

| Malaysian Cantonese | |

|---|---|

| 馬來西亞廣東話/廣府話 Máhlòihsāia Gwóngdūng wá/Gwóngfú wá | |

| Native to | Malaysia |

| Region | Perak, Pahang, Selangor, Kuala Lumpur, Negeri Sembilan, Sandakan |

| Ethnicity | Malaysian Chinese |

| Chinese Characters (Written Cantonese) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

yue-yue | |

yue-can | |

| Glottolog | None |

Malaysian Cantonese is not uniform throughout the country, with variation between individuals and areas. It is mutually intelligible with Cantonese spoken in both Hong Kong and Guangzhou in Mainland China but has distinct differences in vocabulary and pronunciation which make it unique.

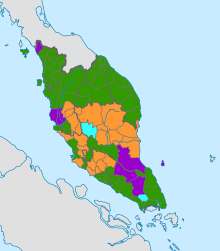

Geographic spread

Cantonese is widely spoken amongst Malaysian Chinese in the capital Kuala Lumpur[1] and throughout much of the surrounding Klang Valley (Petaling Jaya, Ampang, Cheras, Selayang, Sungai Buloh, Puchong, Shah Alam, Kajang, Bangi and Subang Jaya) excluding Klang itself where Hokkien predominates. It is also widely spoken in the town of Sekinchan in the Sabak Bernam district of northern Selangor. It is also used in central and southern Perak, especially in the state capital Ipoh and the surrounding towns of the Kinta Valley region (Gopeng, Batu Gajah and Kampar) as well as the towns of Tapah and Bidor in the Batang Padang district of southern Perak. In Pahang, it is spoken in the state capital Kuantan and the districts of Raub, Bentong, Mentakab and Cameron Highlands.[2][3] Cantonese is also spoken throughout most of Negeri Sembilan, particularly in the state capital Seremban.[4] It is widely spoken in Sandakan, Sabah and Cantonese speakers can also be found in other areas such as Sarikei, Sarawak and Mersing, Johor.[5]

Due to its predominance in the capital city, Cantonese is highly influential in local Chinese-language media and is used in commerce by Malaysian Chinese.[6][7] As a result, Cantonese is widely understood and spoken with varying fluency by Chinese throughout Malaysia, regardless of their dialect group. This is in spite of Hokkien being the most widely spoken variety and Mandarin being the medium of education at Chinese-language schools. The widespread influence of Cantonese is also due in large part to the popularity of Hong Kong media, particularly TVB dramas.

Phonological Differences

A sizeable portion of Malaysian Cantonese speakers, including native speakers, are not of Cantonese ancestry, with many belonging to different ancestral dialect groups such as Hakka, Hokkien and Teochew. The historical and continued influence of their original dialects has produced variation and change in the pronunciation of particular sounds in Malaysian Cantonese when compared to "standard" Cantonese.[8] Depending on their ancestral origin and educational background, some speakers may not exhibit the unique characteristics described below.

- Many Malaysians have difficulty with the ⟨eu⟩ sound and will substitute it with other sounds where it occurs. Often these changes brings the pronunciation of most words in line with their Hakka pronunciation, and for many words their Hokkien pronunciations as well.

- Words that end with ⟨-eung⟩ & ⟨-euk⟩ (pronounced [œːŋ] & [œːk̚] in standard Cantonese) such as 香 hēung, 兩 léuhng, 想 séung and 著 jeuk, 腳 geuk, 約 yeuk may be pronounced as [iɔŋ] & [iɔk̚], which by local spelling conventions may be written as ⟨-iong/-eong⟩ & ⟨-iok/-eok⟩ respectively, e.g. 香 hīong, 兩 líohng, 想 síong and 著 jiok, 腳 giok, 約 yok.[8] This change brings the pronunciation of most words in line with their Hakka pronunciation, and for many words their Hokkien pronunciations as well.

- Words with final ⟨-eun⟩ & ⟨-eut⟩ (pronounced [ɵn] & [ɵt̚] in "Standard" Cantonese) such as 春 chēun and 出 chēut may be pronounced as ⟨-un⟩ [uːn] & ⟨-ut⟩ [uːt̚] respectively.

- Words with final ⟨-eui⟩ (pronounced [ɵy] in "Standard" Cantonese) such as 水 séui and 去 heui may be pronounced as ⟨-oi⟩ [ɔːy], ⟨-ui⟩ [uːy] or even ⟨-ei⟩ [ei] depending on the word.

- Many Malaysians also have difficulty with the ⟨yu⟩ sound (pronounced as [yː] in "Standard" Cantonese) which occurs in words such as 豬 jyū, 算 syun, 血 hyut. This sound may be substituted with [iː] which in the case of some words may involve palatalisation of the preceding initial [◌ʲiː].

- Some speakers, particularly non-native speakers may not differentiate the long and short vowels, such as ⟨aa⟩ [aː] and ⟨a⟩ [ɐ].

- Due to the influence of Hong Kong media, Malaysian Cantonese is also affected by so-called "Lazy Sounds" (懶音 láahn yām) though to a much lesser degree than Hong Kong Cantonese.

- Many younger and middle-aged speakers pronounce some ⟨n-⟩ initial words with an ⟨l-⟩ initial. For many, this process is not complete, with the initial ⟨n-/l-⟩ distinction maintained for other words. e.g. 你 néih → léih.

- Generally, the ⟨ng-⟩ initial has been maintained, unlike in Hong Kong where it is being increasingly dropped and replaced with the null initial. Instead, among some speakers, Malaysian Cantonese exhibits the addition of the ⟨ng-⟩ initial for some words that originally have a null initial. This also occurs in Hong Kong Cantonese as a form of hypercorrection of "Lazy Sounds", e.g. 亞 a → nga.

- Some speakers have lost labialisation of the ⟨gw-⟩ & ⟨kw-⟩ initials, instead pronouncing them as ⟨g-⟩ & ⟨k-⟩, e.g. 國 kwok → kok.

Vocabulary Differences

Malaysian Cantonese is in contact with many other Chinese dialects such as Hakka, Hokkien and Teochew as well other languages such Malay and English.[8] As a result, it has absorbed many loanwords and expressions that may not be found in Cantonese spoken elsewhere. Malaysian Cantonese also preserves some vocabulary which would be considered old fashioned or unusual in Hong Kong but may be preserved in other Cantonese speaking areas such as Guangzhou.[9] Not all of the examples below are used throughout Malaysia, with differences in vocabulary between different Cantonese speaking areas such as Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur and Sandakan. There may also be differences based on the speaker's educational background and native dialect.

- Use of 愛/唔愛 oi/mh oi instead of 要/唔要 yiu/mh yiu to refer to "want/don't want", also meaning "love/like". Also used in Guangzhou and is similar to the character's usage in Hakka.

- More common use of 曉 híu to mean "to be able to/to know how to", whereas 會 wúi/識 sīk would be more commonly used in Hong Kong. Also used in Guangzhou and is similar to the character's usage to Hakka.

- Use of 冇 móuh at the end of sentences to create questions, e.g. 你愛食飯冇? néih oi sihk faahn móuh?, "Do you want to eat?"

- Some expressions have under gone a change in meaning such as 仆街 pūk gāai, literally "fall on the street" which is commonly used in Malaysia to mean "broke/bankrupt" and is not considered a profanity unlike in Hong Kong where it is used to mean "drop dead/go to hell".[10]

- Some English educated speakers may use 十千 sahp chīn instead of 萬 maahn to express 10,000, e.g. 14,000 might be expressed as 十四千 sahp sei chīn instead of 一萬四 yāt maahn sei.

- Use of expressions which would sound outdated to speakers in Hong Kong, e.g. 冇相干 móuh sēung gōn to mean "never mind/it doesn't matter", whereas 冇所謂 móuh só waih/唔緊要 mh gān yiu would be more commonly used in Hong Kong. Some of these expressions are still in current use in Guangzhou.

- Word order, particularly the placement of certain grammatical particles may differ, e.g. 食飯咗 sihk faahn jó instead of 食咗飯 sihk jó faahn for "have eaten."

- Unique expression's such as 我幫你講 ngóh bōng néih góng to mean "I'm telling you" where 我同你講 ngóh tùhng néih góng/我俾你知 ngóh béi néih jī would be used in Hong Kong.

- Malaysian Cantonese is also characterised by the extensive use of sentence ending particles, to an even greater extent than occurs in Hong Kong Cantonese.

| Malaysian | Meaning | Hong Kong | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 擺 báai | Number of times | 次 chi | From Hokkien pai (擺) |

| 蘇嗎 soū/sū mā | All | 全部 chyùn bouh | From Malay semua, many potential pronunciations e.g. sū mūa |

| 巴剎 bā saat | Market/Wet Market | 街市 gāai síh | From Malay pasar, originally from Persian bazaar |

| 馬打 ma dá | Police | 警察 gíng chaat | From Malay mata-mata |

| 馬打寮 ma dá lìuh | Police Station | 警署,[11] gíng chyúh | |

| 扮𠮨 baan naai | Clever | 聰明 chūng mìhng/叻 lēk | From Malay pandai |

| 千猜 chīn chāai | Whatever/Casually | 是但 sih daahn | Also used in Malay Cincai and in Hokkien |

| 軋爪 gaat jáau | To Annoy | 煩 fàahn | From Malay kacau |

| Sinang sīn nāang | Easy | 容易 yùhng yih | From Malay senang |

| Loti lo di | Bread | 麵包 mihn bāau | From Malay roti, originally from Tamil/Sanskrit |

| Kopi go bī | Coffee | 咖啡 ga fē | From Malay Kopi |

| 鐳 lūi/lēui | Money | 錢 chìhn | From Malay duit or Hokkien lui (鐳) |

| 箍 kāu | Units of Currency (Ringgit/Dollar) | 蚊 mān | Related to Hokkien khoo (箍) |

| 黃梨 wòhng láai* | Pineapple | 菠蘿 bō lòh | Pronunciation differs, based on Hokkien |

| 弓蕉 gūng jīu | Banana | 香蕉 hēung jīu | |

| 落水 lohk séui | Raining | 落雨 lohk yúh | From Hakka |

| 撩 lìuh | To Play | 玩 wàahn | Derived from Hakka 尞 |

| 啦啦 lā lā | Clam | 蛤 gaap | |

| 啦啦仔 lā lā jái | MK仔 MK jái | ||

| 水草 séui chóu | Drinking straw | 飲管 yám gún | |

| 跳飛機 tiu fēi gēi | Illegal immigration | 非法移民 fēi faat yìh màhn | |

| 書館 syū gún/學堂 hohk tòhng | School | 學校 hohk haauh | |

| 堂/唐 tòhng | Classifier for vehicles e.g. cars | 架 gá | e.g. "2 Cars", 兩堂車 léuhng/líohng tòhng chē (Malaysia), 兩架車 léuhng gá chē (Hong Kong) |

| 腳車 geuk/giok chē | Bicycle | 單車 dāan chē | |

| 摩哆 mo dō | Motorcycle | 電單車 dihn dāan chē | From English motorcycle |

| 三萬 sāam maahn | Fine/Penalty | 罰款 faht fún | From English summons |

| 泵質 būng jāt | Punctured | 爆胎 baau tōi | From English punctured |

| 禮申 láih sān | Licence | 車牌 chē pàaih | From English licence |

See also

References

- 《马来西亚的三个汉语方言》中之 吉隆坡广东话阅谭 (PDF) (in Chinese). New Era University College. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (30 November 2004). "Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities". Springer Science & Business Media – via Google Books.

- Leitner, Gerhard; Hashim, Azirah; Wolf, Hans-Georg (11 January 2016). "Communicating with Asia: The Future of English as a Global Language". Cambridge University Press – via Google Books.

- Gin, Ooi Keat (11 May 2009). "Historical Dictionary of Malaysia". Scarecrow Press – via Google Books.

- Astro AEC, Behind the Dialect Groups, Year 2012

- Malaysian Cantonese Archived May 27, 2014, at Archive.today

- Tze Wei Sim, Why are the Native Languages of the Chinese Malaysians in Decline. Journal of Taiwanese Vernacular, p. 74, 2012

- Wee Kek Koon (2018-11-01). "Why Cantonese spoken in Malaysia sounds different to Hong Kong Cantonese, and no it's not 'wrong'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- Wee Kek Koon (2017-04-20). "Southeast Asian Cantonese – why Hongkongers should not ridicule it". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- http://www.cantonese.sheik.co.uk/dictionary/words/1679/

- "联络我们". 香港警务处.