Tilefish

Tilefishes are mostly small perciform marine fish comprising the family Malacanthidae.[1][2] They are usually found in sandy areas, especially near coral reefs.[3]

| Tilefishes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Blue blanquillo, Malacanthus latovittatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Malacanthidae Poey, 1861 |

| Subfamilies & Genera[1] | |

|

Subfamily Latilinae Subfamily Malacanthinae | |

Commercial fisheries exist for the largest species, making them important food fish. However, the US Food and Drug Administration warns pregnant or breastfeeding women against eating tilefish and some other fish due to mercury contamination. [4][5] The smaller, exceptionally colorful species of tilefish are enjoyed in the aquarium.

Taxonomic issues

The family is further divided into two subfamilies: Latilinae (=Branchiosteginae) and Malacanthinae.[2][6] Some authors regard these subfamilies as two evolutionarily distinct families.[1][2]

Description

The two subfamilies appear to be morphologically different, with members of the Latilinae having deeper bodies bearing predorsal ridge and heads rounded to squarish in profile. In contrast, members of the Malacanthinae are more slender with elongated bodies lacking predorsal ridge and rounded head. They also differ ecologically, with latilines typically occurring below 50 m and malacanthines shallower than 50 m depth.[2]

Tilefish range in size from 11 cm (yellow tilefish, Hoplolatilus luteus) to 125 cm (great northern tilefish, Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps) and a weight of 30 kg.

Both subfamilies have long dorsal and anal fins, the latter having one or two spines. The gill covers (opercula) have one spine which may be sharp or blunt; some species also have a cutaneous ridge atop the head. The tail fin may range in shape from truncated to forked. Most species are fairly low-key in colour, commonly shades of yellow, brown, and gray. Notable exceptions include three small, vibrant Hoplolatilus species: the purple sand tilefish (H. purpureus), Starck's tilefish (H. starcki), and the redback sand tilefish (H. marcosi).

Tilefish larvae are notable for their generous complement of spines and serrations on the head and scales. This feature also explains the family name Malacanthidae, from the Greek words mala meaning "many" and akantha meaning "thorn".

Habitat and diet

Generally shallow-water fish, tilefish are usually found at depths of 50–200 m in both temperate and tropical waters of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. All species seek shelter in self-made burrows, caves at the bases of reefs, or piles of rock, often in canyons or at the edges of steep slopes. Either gravelly or sandy substrate may be preferred, depending on the species.[7]

Most species are strictly marine; an exception is found in the blue blanquillo (Malacanthus latovittatus) which is known to enter the brackish waters of Papua New Guinea's Goldie River.

Tilefish feed primarily on small benthic invertebrates, especially crustaceans such as crab and shrimp. Mollusks, worms, sea urchins, and small fish are also taken.

After the 1882 mass die-off,[8] great northern tilefish were thought to be extinct until a large number were caught in 1910 near New Bedford, Massachusetts.[9]

Behaviour and reproduction

Active fish, tilefish keep to themselves and generally stay at or near the bottom. They rely heavily on their keen eyesight to catch their prey. If approached, the fish quickly dive into their constructed retreats, often head-first. The chameleon sand tilefish (Hoplolatilus chlupatyi) relies on its remarkable ability to rapidly change colour (with a wide range) to evade predators.

Many species form monogamous pairs, while some are solitary in nature (e.g., ocean whitefish, Caulolatilus princeps), and others colonial. Some species, such as the rare pastel tilefish (Hoplolatilus fronticinctus) of the Indo-Pacific, actively builds large rubble mounds above which they school and in which they live. These mounds serve as both refuge and as a microecosystem for other reef species.

The reproductive habits of tilefish are not well studied. Spawning occurs throughout the spring and summer; all species are presumed not to guard their broods. Eggs are small (<2 mm) and made buoyant by oil. The larvae are pelagic and drift until the fish have reached the juvenile stage.

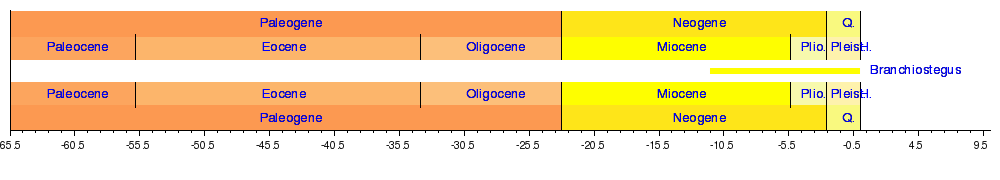

Timeline

Health effects

Tilefish from the Gulf of Mexico have been shown to have high levels of mercury, and the FDA has recommended against their consumption by pregnant women.[10] Atlantic Ocean tilefish may have lower levels of mercury and may be safer to consume.[11]

Gallery

- Branchiostegus wardi

Great northern tilefish, Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps

Great northern tilefish, Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps Hoplolatilus randalli

Hoplolatilus randalli

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malacanthidae. |

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2015). "Malacanthidae" in FishBase. October 2015 version.

- Nelson, J. S. (2006). Fishes of the World (4 ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 357–358. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- Discoverlife.org

- FDA (1990–2010). "Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish". Retrieved 2011-09-14.

- Melody Joy Kramer (October 17, 2006). "Fish FAQ: What You Need to Know About Mercury". Retrieved 2011-09-14.

- Eschmeyer, W. N. and R. Fricke (eds) (4 January 2016). "Species by family/subfamily in the Catalog of Fishes". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 18 January 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Baird, Troy A. (1988). "Female and male territoriality and mating system of the sand tilefish, Malacanthus plumieri". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 22 (2): 101–116. doi:10.1007/BF00001541.

- Marsh, Robert; Petrie, Brian; Weidman, Christopher R.; Dickson, Robert R.; Loder, John W.; Hannah, Charles G.; Frank, Kenneth; Drinkwater, Ken (1999). "The 1882 tilefish kill—a cold event in shelf waters off the north‐eastern United States?". Fisheries Oceanography. 8 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2419.1999.00092.x.

- "Tile Fish Reappears". New York Times. 2 July 1910.

- "Fish: What Pregnant Women and Parents Should Know".

- "Atlantic Tilefish Are Absolved, F.D.A. advisory says ocean species low in mercury; fishermen vindicated". The East Hampton Star.

Further reading

- Eol.org

- Acero, A. and Franke, R., (2001)., Peces del parque nacional natural Gorgona. En: Barrios, L. M. y M. Lopéz-Victoria (Eds.). Gorgona marina: Contribución al conocimiento de una isla única., INVEMAR, Serie Publicaciones Especiales No. 7:123–131.

- Breder, C.M. Jr., (1936)., Scientific results of the second oceanographic expedition of the "Pawnee" 1926. Heterosomata to Pediculati from Panama to Lower California., Bull. Bingham Oceanogr. Collect. Yale Univ., 2(3):1–56.

- Béarez, P., 1996., Lista de los Peces Marinos del Ecuador Continental., Revista de Biología Tropical, 44:731–741.

- Castro-Aguirre, J.L. and Balart, E.F., (2002)., La ictiofauna de las islas Revillagigedos y sus relaciones zoogeograficas, con comentarios acerca de su origen y evolucion. En: Lozano-Vilano, M. L. (Ed.). Libro Jubilar en Honor al Dr. Salvador Contreras Balderas., Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo León:153–170.

- Dooley, J.K., (1978)., Systematics and biology of the tilefishes (Perciformes: Branchiostegidae and Malacanthidae), with descriptions of two new species., U.S. Nat. Ocean. Atmos.