Madison Street Bridge disaster

The Madison Street bridge disaster occurred on November 1, 1893, in Portland, Oregon, United States, when a westbound streetcar drove off the open draw of the first Madison Street Bridge (since replaced by the Hawthorne Bridge). Seven people died. This remains the worst streetcar accident ever to occur in the city of Portland[1][2] and also the worst bridge disaster in Portland history.[3]

| Madison Street Bridge disaster | |

|---|---|

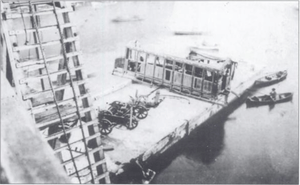

The streetcar Inez raised after falling into the Willamette River | |

| Details | |

| Date | November 1, 1893 6:45 a.m. |

| Location | Portland, Oregon |

| Coordinates | 45.5134°N 122.6712°W |

| Line | East Side Railway |

| Incident type | Streetcar ran off open drawbridge into river |

| Cause | Excessive speed, poor warning systems, icy track |

| Statistics | |

| Passengers | 18-20 |

| Crew | 2 |

| Deaths | 7 |

| Damage | Streetcar Inez destroyed |

The first Madison Street Bridge

Opened in January 1891, the first Madison Street Bridge was a swing bridge which pivoted on a large central trunnion mounted on a piling structure in the river.[4] The bridge was poorly designed.[4] At the time of the accident, the bridge was owned by the City of Portland.[5]

The disaster

Opening the draw

On November 1, 1893, in foggy weather after dawn, the sternwheeler Elwood approached the bridge, and gave the signal to open the draw, one long and three short blasts on the steam whistle.[6][7] To allow the steamer to pass, the bridge operator swung open the swinging draw section of the bridge.[6] The bridge tender closed the wooden gates on each side of the draw and hung a red signal light as a warning.[8]

The streetcar approaches

At about 6:45 a.m. on November 1, 1893, the streetcar Inez, owned by the East Side Railway Company, arrived at the Madison Street Bridge, running westbound into the city with 18 to 20 passengers on board, as well as the motorman and the conductor.[9] All the streetcars were named in those times.[7][8] Inez was coming from Milwaukie.[9] Some passengers got off, and one witness said there were about 15 passengers on board when the car reached the bridge.[10] The night before had been cold and frost covered the rails.[9] The car had departed from Oak Grove at about 5:55 a.m. that morning.[10]

Policeman J. J. Flynn, whose post was on the east side of the bridge, stated that he had seen the streetcar pass and had thought it was running somewhat fast, but he paid not too much attention to it.[9] His job was to make sure that carts and horse-drawn vehicles slowed to a walking pace when crossing the bridge.[9] However, he had received no instructions as to speeds of the trolleys. His statement concluded, however: "I think the car was running too fast."[9]

Captain Lee, on Elwood, said to a reporter on November 1 that he could see the light on the car, and from the sound, he thought it was moving fast across the bridge, and the motorman might not realize that the draw was open.[10]

Shouted and whistled warnings

An 18-year-old man, Joe Kutcher, saw the streetcar move onto the bridge and thought nothing of it, until he heard someone behind him shout "Stop that car!"[9] A messenger boy for a local brewery, W. B. Crabtree, also walking across the bridge, heard someone shout: "Stop the car! The bridge is open!".[7] On the steamer Elwood, Captain Lee sounded the Elwood's whistle hard, hoping the motorman would hear it and realize the danger.[10]

Brakes fail to stop the car

The motorman, Edward F. Terry, gave a sworn statement before Portland Mayor William S. Mason (1832–1899) and chief of police Hunt.[9] According to the motorman, he had not seen the red light indicating the draw was open until one bridge span (about 80 feet) away.[9] He tried applying the brakes, but the car slid along the track.[9] He jumped from the car onto the bridge before it went over the gap into the river.[9]

The conductor, W. C. Powers, also gave a statement.[9] He said the car was not going very fast as it started across the bridge.[9] As soon as he saw the red light, he opened the trolley's door and alerted the passengers to jump from the car.[9] The conductor then jumped himself, just before the car struck the wooden gate before the open draw.[9] He saw a number people jump off the car.[9]

The car goes into the river

In 1893, Kutcher stated that he had turned and saw the car about 20 feet (6.1 m) from the gate, and coming very fast.[9] According to Kutcher's statement:

The motorman had his head turned to one side, as if looking for the person who had shouted to him, and then he turned and looked ahead again.[9] It seemed to me that then he saw for the first time the signal light, for he commenced to turn the brake handle very tight.[9] But he could not stop the car, which went ahead and smashed through the gate.[9]

Kutcher saw the car teeter briefly on the brink, and then fall into the water.[9] He saw a man's head, wearing a black hat, appear above the surface, just before the steamer passed over him.[9]

Two passengers on the car, G. W. Hoover and William Kenner, who had both leapt from the car, both agreed there were only three people on the car when it went off the bridge.[10] This proved to be inaccurate.

On Elwood, Captain Lee saw the car go into the river.[10] Lee said at the time that had the Elwood been just about a boat length ahead, the car would have struck the steamer.[10]

Attempted rescue of people in the water

Mr. Hoover was evidently too badly excited to see things clearly. Instead of plowing through and running down the passengers, the Elwood stopped before reaching the draw tying up at the pivot pier, and rendered every possible assistance to the unfortunates. We threw overboard life preservers, planks and staging and succeeded in rescuing the only man who fell in the water and escaped with his life. While we were tied up at the pier we sent out a small boat and took aboard the man who was floating on the Elwood's foot plank.

Jas. Lee, captain

Alex. Gordon, mate

Passenger G. W. Hoover said that he had been riding on the car, and had to push a woman, who he said was paralyzed with fear, out of the car ahead of him.[9] Hoover also said he saw the steamer Elwood pass through the draw, and run over two men who were struggling in the water.[9] Hoover said the steamer made no attempt to slow down.[9]

Hoover's account of Elwood's actions was disputed by the boat's captain, James Lee, and the mate and the fireman.[9] They stated that the steamer stopped before reaching the draw, tied up at the pivot pier, and did everything possible to help the people in the water, throwing over life-preservers, planks and staging.[9] They said they had launched a boat to try to save people.[9] Using the boat, they rescued the only man who survived the car's plunge into the river, who was found floating on the Elwood's gangplank.[9]

The Morning Oregonian reported that right after Elwood passed through the draw, the steamer had lowered a boat to attempt to save two men who were still struggling to stay afloat in the water.[9] One man sank before they could reach him, and the other was dead when the boat picked him up.[9]

G. W. Hoover and Captain Lee later composed their differences.[11] Lee and Hoover came together to The Oregonian on the evening of November 7, 1893.[11] Hoover said that he was now satisfied, from the testimony of the other witnesses, that Lee had done everything he could have to save the people in the accident.[11] Hoover also said that he had obtained the dismissal of the criminal charges which Hoover had brought against Lee.[11] Lee denied that he had dragged Hoover to the morgue, and said that Hoover had gone willingly.[11]

Recovery of bodies and salvage

Thousands of people gathered on the bridge and the docks in the area, and exaggerated rumors of the scale of the accident spread through the city.[8] An hour after the accident, drag lines were being used to find bodies, and at 9:30 the first one was recovered, and immediately identified as that of John P. Anderson, a cabinet maker from Milwaukie.[8] By 11:00 a.m. the bodies of Alexander Campbell, a saloon keeper from Midway and Jasper Stadler, a laborer from Oak Grove, were recovered.[8] At that time the tug C.M. Belshaw brought two construction barges to the wreck site, to use their hoisting equipment to recover the streetcar.[8]

A diver, George A. Tilden, brought his equipment out to one of the barges, and at 1:15 p.m. he made his first dive.[8] Tilden found the streetcar on the bottom of the river, in water about 35 feet (11 m) deep, tipped slightly to one side and lying nearly parallel to the bridge.[8] The car had come off the trucks, and the roof was completely crushed.[8] The platform had been separated from the car body, and half of one side of the car had been smashed.[8] The car interior was so jammed with wreckage that Tilden could neither enter the interior nor determine whether there were any bodies inside.[8]

At 2:00 p.m. Tilden was able to secure heavy chains to each end of the car, and when he returned to the barge, the chains were cranked up slowly to raise the car.[8] When the car broke the surface, people in rowboats, who had come out to watch, slipped under the ropes placed around the area, impeding the operation.[8]

Before the car was completely raised, the hoist was stopped while the police, under Captain Holmberg, searched the car.[8] They found one body inside, that of Theodore Bennick, also a cabinet maker from Milwaukie, who was identified by a memo book found in a pocket.[8] Tilden went down again to search for more bodies, but none were found, and concluded his diving work at 4:30 p.m. that day.

The two missing persons, whose bodies were not found, were Paul Oder, bottling department foreman at the Gambrinus brewery, and a boy, Charles S. Albee, aged 14, who worked as a paper hanger.[8] Their bodies were initially presumed to have washed downstream, but were later recovered, Oder's on the evening of November 2 and Albee's on the morning of November 3, 1893.[12] As of Thursday, November 3, a man named Peterson was still missing, who would be the eighth victim.[12]

The coroner's jury

A coroner's jury was convened on the evening November 2.[13] The motorman and the conductor testified, giving statements similar to what they had told the police on the day of the accident.[12]

J. C. Cooper, a motorman with two years' experience on the Washington Street streetcar line, testified that a major factor in causing the accident was frost on the rails, and that even the use of sand (which the Inez did not have) would not have prevented the wheels from slipping on the rail.[12]

George A. Steel, president of the East Side Railway Company, also testified before the coroner's jury.[12] Steel's evidence was that the company had no control over the Madison Street bridge, the gates, or the draw.[12] The city had purchased the bridge some time before, and the company only paid the city rent for use of the bridge for the streetcar line.[12]

The coroner's jury continued to take evidence on Friday morning, November 3.[14] W. A. Burkholder, assistant superintendent of the Portland General Electric Light Company, testified that on the morning of the accident, that the ice on the rails "acted like grease" and that sand would have slowed the car.[14] An electrical warning system could be set up on the Morrison bridge at a small cost.[14]

W. B. Chase, engineer of the Portland bridge commission, testified that the only safety warning devices on the Madison Street bridge were the gates at the draw and a red warning light, although in foggy weather a gong was kept sounding when the draw was open.[14] When the draw was open early in the morning, no one was placed at the east side of bridge to caution traffic, although during the day and the evening, two men were placed on duty.[14] The gates were not placed to stop streetcars.[14] A gate that could wreck a streetcar could be built, but these were not ordinarily placed on bridges.[14]

Chase testified further that the bridge commission had considered the speed of streetcars across the bridge, but had been unable to control it.[14] He had issued an order to have motormen cross the bridge very slowly, but this order had been violated, and he had to have President Steel issue new orders.[14] Chase agreed with Burkholder that an electric signal system could be established.[14]

Chase testified that the means of stopping cars on the bridge was not within the responsibility of the bridge commission.[14]

On the evening of Friday, November 3, 1893, the coroner's jury completed its investigation and returned its findings and recommendations.[13][15] The jury found that the motorman was grossly negligent, by running the car at excessive speed across the bridge when the rails were slippery from ice and the weather was foggy.[14][15] The jury recommended that a better system of warning signals be installed on the bridge.[15] The jury commended Captain Lee and the crew of the Elwood for their work in attempting to rescue the people in the water.[15]

Witness brings charges against steamer captain

G. W. Hoover, the passenger who said Elwood had run down two passengers in the water, swore out an affidavit in support of a warrant for the arrest of Captain Lee, claiming that Lee had threatened to kill him.[13] According to Hoover, "Captain Lee called at my place of business and demanded to see me, but was so excited that they would not permit him to do so. He threatened to kill me, and kept his hand on his hip pocket. He wanted me to go aboard his boat, where he said he had twenty-five men to testify that he had not run down any men in the water."[13]

Criminal charges against the motorman

Criminal charges were brought against the motorman of Inez, Edward F. Terry.[16] On Friday, February 2, 1894, Judge Manley sustained Terry's demurrer to the indictment filed against him, and ordered the case resubmitted to the grand jury.[16] This was the second time that the indictment had been resubmitted to the grand jury.[16]

Company ruined

The lawsuits associated with the accident ruined the East Side Railway, which was forced into receivership on December 9, 1893.[1]

Notes

- Labbe, John T. (1980). Fares Please! Those Portland Trolley Years. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0-87004-287-4. LCCN 79-50502.

- Thompson, Richard (2006). Portland's Streetcars. Arcadia Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 0-7385-3115-4.

- Wood Wortman, Sharon; Wortman, Ed (2006). The Portland Bridge Book (3rd ed.). Urban Adventure Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-9787365-1-6.

- Historic American Engineering Report, National Park Service. Hawthorne Bridge: Spanning Willamette River on Hawthorne Boulevard, Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. p.2.

- "The Portland Bridge Horror". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. November 1, 1893. p. 4 col. 5.

- Timmen, Fritz (August 17, 1969). "The Night the Trolley Car Sank". Sunday Oregonian (Northwest Magazine). Portland, Oregon. pp. 59–60.

- Crabtree, W. B. (September 14, 1969). "Letters". Sunday Oregonian (Northwest Magazine). Portland, Oregon. p. 2.

- "Open Draw: Causes a Frightful Accident on the Madison Street Bridge: Hurled Into Eternity". Oregon City Enterprise. Oregon City, OR. November 3, 1893. p. 6 col. 2.

- "It Was a Swift Death: An Appalling Street Railway Accident: Drowned like Caged Rats". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. November 2, 1893. p. 1.

- "Seven Were Drowned In the Madison Street Bridge Disaster. Result of the Coroner's Inquest: Detailed Statement of Persons on the Wreck". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. November 2, 1893. p. 1 col. 3.

- "City News in Brief: They Have Buried the Hatchet". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. November 8, 1893. p. 5 col. 1.

- "More About the Wreck: Another Man Believed to Be Among the Missing". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. November 3, 1893. p. 1 col. 4.

- "The Inquest Ended: The Motorman Is Censured: He Is Charged With Being Grossly Negligent--Recommendations by the Jury". Morning Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. November 4, 1892. p. 8.

- "Portland Bridge Disaster: More Testimony Taken on Coroner's Inquest — The Jury's Report". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. November 4, 1893. p. 1.

- "The Jury's Work is Done: A Charge of Gross Negligence Against the Motorman". Daily Morning Astorian. Astoria, OR. November 4, 1893. p. 1 col. 5.

- "Items from Portland … The demurrer of F. Terry, motorman …". Capital Journal. Salem, OR. February 5, 1894. p. 1 col. 6.

References

Printed sources

- Labbe, John T. (1980). Fares Please! Those Portland Trolley Years. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers. ISBN 0-87004-287-4. LCCN 79-50502.

- Mills, Randall V. (1947). Sternwheelers up Columbia -- A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7. LCCN 77007161.

- Thompson, Richard (2006). Portland's Streetcars. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3115-4.

- Timmen, Fritz (1973). Blow for the Landing -- A Hundred Years of Steam Navigation on the Waters of the West. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers. ISBN 0-87004-221-1. LCCN 73150815.