MEMS magnetic actuator

A MEMS magnetic actuator is a device that uses the microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) to convert an electric current into a mechanical output by employing the well-known Lorentz Force Equation or the theory of Magnetism.

Overview of MEMS

Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS) technology[1] is a process technology in which mechanical and electro-mechanical devices or structures are constructed using special micro-fabrication techniques. These techniques include: bulk micro-machining, surface micro-machining, LIGA, wafer bonding, etc.

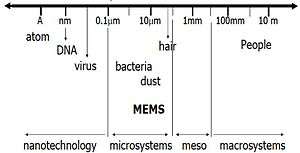

A device is considered to be a MEMS device if it satisfies the following:

- If its feature size is between 0.1 µm and hundreds of micrometers. (below this range, it becomes a nano device and above the range, it is considered a mesosystem)

- If it has some electrical functionality in its operation. This could include the generation of voltage by electromagnetic induction, by changing the gap between 2 electrodes or by a piezoelectric material.

- If the device has some mechanical functionality such as the deformation of a beam or diaphragm due to stress or strain.

- If it has a system-like functionality. The device must be integrable to other circuitries to form a system. This would be the interfacing circuitry and packaging for the device to become useful.

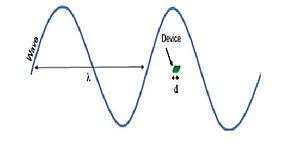

For the analysis of every MEMS device, the Lumped assumption is made: that if the size of the device is far less than the characteristic length scale of the phenomenon (wave or diffusion), then there would be no spatial variations across the entire device. Modelling becomes easy under this assumption.[2]

Operations in MEMS

The three major operations in MEMS are:

- Sensing: measuring a mechanical input by converting it to an electrical signal, e.g. a MEMS accelerometer or a pressure sensor (could also measure electrical signals as in the case of current sensors)

- Actuation: using an electrical signal to cause the displacement (or rotation) of a mechanical structure, e.g. a synthetic jet actuator.

- Power generation: generates power from a mechanical input, e.g. MEMS energy harvesters

These three operations require some form of transduction schemes, the most popular ones being: piezoelectric, electrostatic, piezoresistive, electrodynamic, magnetic and magnetostrictive. The MEMS magnetic actuators use the last three schemes for their operation.

Magnetic actuation

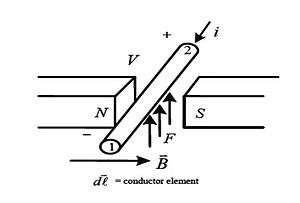

The principle of magnetic actuation is based on the Lorentz Force Equation.

When a current-carrying conductor is placed in a static magnetic field, the field produced around the conductor interacts with the static field to produce a force. This force can be used to cause the displacement of a mechanical structure.

Governing equations and parameters

A typical MEMS actuator is shown on the right. For a single turn of circular coil, the equations that govern its operation are:[3]

- The H-field from a circular conductor:

- The force produced by the interaction of the flux densities:

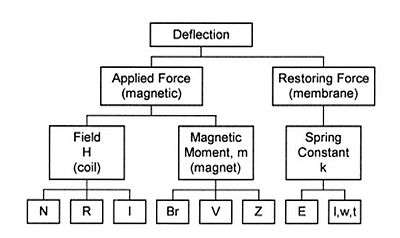

The deflection of a mechanical structure for actuation depends on certain parameters of the device. For actuation, there has to be an applied force and a restoring force. The applied force is the force represented by the equation above, while the restoring force is fixed by the spring constant of the moving structure.

The applied force depends on both the field from the coils and the magnet. The remanence value of the magnet,[4] its volume and position from the coils all contribute to its effect on the applied Force. Whereas the number of turns of coil, its size (radius) and the amount of current passing through it determines its effect on the Applied Force. The spring constant depends on the Young's Modulus of the moving structure, and its length, width and thickness.

Magnetostrictive actuators

Magnetic actuation is not limited to the use of Lorentz force to cause a mechanical displacement. Magnetostrictive actuators can also use the theory of magnetism to bring about displacement. Materials that change their shapes when exposed to magnetic fields can now be used to drive high-reliability linear motors and actuators..

An example is a nickel rod that tends to deform when it is placed in an external magnetic field. Another example is wrapping a series of electromagnetic induction coils around a metal tube in which a Terfenol-D material is placed. The coils generate a moving magnetic field that courses wavelike down the successive windings along the stator tube. As the traveling magnetic field causes each succeeding cross section of Terfenol-D to elongate, then contract when the field is removed, the rod will actually "crawl" down the stator tube like an inchworm. Repeated propagating waves of magnetic flux will translate the rod down the tube's length, producing a useful stroke and force output. The amount of motion generated by the material is proportional to the magnetic field provided by the coil system, which is a function of the electric current. This type of motive device, which features a single moving part, is called an elastic-wave or peristaltic linear motor. (view:

Video of a Magnetostrictive micro walker)

Advantages of magnetic actuators

- High actuation force and stroke (displacement)

- Direct, fully linear transduction (in the case of electrodynamic actuation)

- Bi-directional actuation

- Contactless remote actuation

- Low-voltage actuation

- A figure of merit for actuators is the density of field energy that can be stored in the gap between the rotor and stator. Magnetic actuation has a potentially high energy density[5]

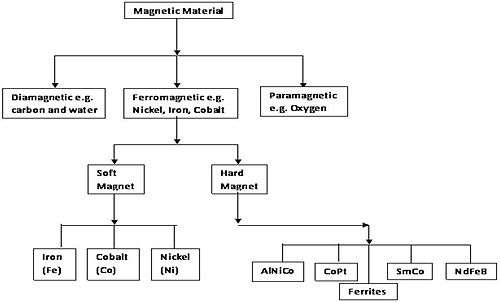

Magnet material

The operation of the magnetic actuator depends on the interaction between the field from an electromagnet and a static field. To produce this static field, it is important to use the right material. In MEMS, permanent magnets have become the favorite because they have a very good scaling factor and they retain their magnetization even when there is no external field... meaning that they need not be continuously magnetized when they are in use[6][7][8][9][10]

Integrating the magnet into the MEMS device

As earlier discussed, MEMS devices are designed and fabricated using special micro-fabrication techniques. The major challenge however for magnetic MEMS is the integration of the magnet into the MEMS device.[11][12] Recent research has suggested solutions to this challenge.

Fabrication (or molding) of the magnet

There are several ways by which the magnet could be fabricated on a MEMS structure:

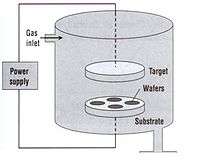

- Sputtering: Argon ion bombardment of the material release particles of the material. Mainly for depositing rare earth magnets. Deposition rate and film surface area depend on sputtering tool and target size

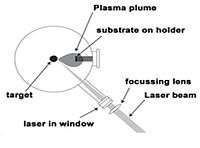

- Pulsed Layer Deposition: a high-power pulsed laser beam is focused inside a vacuum chamber to strike a target of the material that is to be deposited

- Electroplating

- Screen printing

- Wax/Parylene bonding[13][14][15]

Issues with magnetic actuation

- High-power dissipation. This is a major problem for magnetic MEMS, but work is underway to circumvent this.[16]

- Fabrication of the coil

- Integration of the micromagnet into the MEMS device

- Process-material compatibility

- Integratability into the overall microfabrication process (maintain cost and throughput)

- So that preexisting processes in the fabrication of the MEMS device will not be tampered with, deposition temperatures and post-deposition treatment/conditions must be tolerable. Also, the micromagnet must be able to withstand any chemical treatment that will come after its deposition

- Issues with magnetization (One may want to have more than one direction of magnetization; this creates a problem)[17]

Each of these challenges can be mitigated or lessened by the right choice of material, choice of molding or fabrication method, and the type of device that is to be constructed. Applications of the magnetic actuator include: the synthetic jet actuator, micro-pumps and micro-relays.

References

- Senturia, Stephen D. (2001). Microsystem Design. ISBN 978-0-7923-7246-2.

- Arnold, D. (Fall 2010 & Spring 2011). Lecture Notes on MEMS Transducers. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - Wagner, B.; w. Benecke. "Microfabricated Actuator with moving Permanent Magnet". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dodrill, B. C.; B. J. Kelley. "Measurement with a VSM – Permanent Magnet Materials". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Arnold, D. "Permanent Magnets for MEMS". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gibbs, M R J; E W Hill; P J Wright. "Magnetic Materials for MEMS Applications". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - National Imports LLC. "Permanent Magnet Selection and Design Handbook". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Arnold, D. "Permanent Magnets for MEMS". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wang, N. (2010). "Fabrication and Integration of Permanent Magnet Materials into MEMS Transducers". Bibcode:2010PhDT........49W. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Arnold, David. "Permanent magnets for MEMS". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Schiavone, Giuseppe; Desmulliez, Marc P. Y.; Walton, Anthony J. (2014-08-29). "Integrated Magnetic MEMS Relays: Status of the Technology". Micromachines. 5 (3): 622–653. doi:10.3390/mi5030622.

- Chin, Tsung-Shune (2000). "Permanent magnet films for applications in Micro-electro-mechanical systems". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 209 (1): 75–79. Bibcode:2000JMMM..209...75C. doi:10.1016/S0304-8853(99)00649-6.

- Arnold, D.; B. Bowers; N. Wang (2008). "Wax-bonded NdFeB micromagnets for microelectromechanical systems applications". Journal of Applied Physics. 103 (7): 07E109. Bibcode:2008JAP...103gE109W. doi:10.1063/1.2830532.

- Wang, N. (2010). "Fabrication and Integration of Permanent Magnet Materials into MEMS Transducers". Bibcode:2010PhDT........49W. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Yang, Tzu-Shun; Naigang Wang; David P. Arnold. "Fabrication and characterization of parylene-bonded Nd–Fe–B powder micromagnets". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Guckel, H. "Progress in Magnetic Microactuators". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gatzen, Hans H. "Advances in European Magnetic MEMS Technology". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)