M1895 Lee Navy

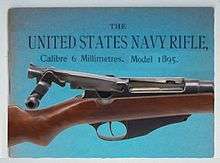

The Lee Model 1895 was a straight-pull, cam-action magazine rifle adopted in limited numbers by the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps in 1895 as a first-line infantry rifle.[3] The Navy's official designation for the Lee Straight-Pull rifle was the "Lee Rifle, Model of 1895, caliber 6-mm"[3] but the weapon is also largely known by other names, such as:

- Winchester-Lee rifle

- Model 1895 Lee Navy

- 6mm Lee Navy

- Lee Rifle, Model of 1895

- etc.

| Lee Rifle, Model of 1895, Caliber 6mm | |

|---|---|

| Type | Bolt-action rifle |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1895–1907 |

| Used by | United States Navy |

| Wars | Spanish–American War Philippine–American War Boxer Rebellion Moro Rebellion |

| Production history | |

| Designer | James Paris Lee |

| Manufacturer | Winchester Repeating Arms Company |

| Produced | 1895 |

| No. built | Approx. 15,000[1] |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 8.32 pounds (3.77 kg) |

| Length | 47.75 in (121.3 cm) |

| Barrel length | 28 in (71 cm) |

| Cartridge | 6mm Lee Navy[2] |

| Action | Straight-pull bolt action |

| Muzzle velocity | 779 m/s (2,560 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range | 549 m (600 yd) individual target, 915 m (1,000 yd) massed target |

| Maximum firing range | 1829 m (2,000 yd) |

| Feed system | 5-round en bloc clip, internal box magazine |

| Sights | Blade front, U-notch rear, adjustable for windage/elevation |

It fired a 6mm (0.236-in. caliber) cartridge,[3] which used an early smokeless powder,[4][5] was semi-rimless, and fired a 135-grain (later 112-grain) jacketed bullet.[2][3] The 6mm U.S.N. or Lee Navy Cartridge was also used in the navy version of the Colt–Browning Model 1895 machinegun.[2][6]

Production history and development

By 1894, the U.S. Navy desired to adopt a modern small-bore, smokeless powder rifle in keeping with other first-line naval powers. Naval authorities decided that the new cartridge should be adaptable to both rifles and machine guns. As the military forces began adopting smaller and smaller caliber rifles with higher velocity cartridges, U.S. naval authorities decided to leapfrog developments by adopting a semi-rimless cartridge in 6-mm caliber, with a case capable of holding a heavy charge of smokeless powder.[7] On August 1, 1894 a naval test board was convened at the Naval Torpedo Station in Newport, Rhode Island to test submitted magazine rifles in the new 6mm Navy government chambering.[8] Per the terms of the Notice to Inventors, the new government-designed 6mm U.S.N a.k.a. Ball Cartridge, 6mm was the only cartridge permitted for rifles tested before the Naval Small Arms Board.[8] Both the ammunition and rifle barrels were supplied by the government; the barrels, made of 4.5 per cent nickel steel, used Metford-pattern rifling with a rifling twist of one turn in 6.5 inches, and were supplied unchambered with the receiver thread uncut.[2][8] The rifle action was required to withstand the firing of five overpressure (proof) cartridges with a chamber pressure of 60,000 psi.[8]

In the first set of service trials, the naval small arms board tested several submissions, including the Van Patten, Daudeteau, Briggs-Kneeland, Miles, the Russell-Livermore Magazine Rifle, five Remington turnbolt designs (all with side-mounted magazines), and the Lee straight-pull.[9] In a second set of trials the Model 1893/94 Luger 6-mm Rifle[10] and the Durst rifle were also considered, along with a Lee turning-bolt design.[9] The Durst prototype fractured the receiver in firing and was withdrawn from the test, while the Luger Rifle performed excellently. Luger's submission had only one major disadvantage: it failed to meet government specifications, having been chambered in a non-standard rimless 6mm cartridge.[9] The Lee turning bolt design was considered to be a good one, but marred by its magazine system, which the Small Arms Board found to be problematic.[9] The Board thought so highly of the Luger Rifle that it recommended purchase of either a prototype or an option to purchase the rights to manufacture.[9] Apparently this never came to pass, as Luger not only declined to submit its design in the Navy's government 6mm chambering, but withdrew from the third round of the service trials.[9] The Lee straight-pull rifle with its clip-loaded magazine was chosen as the winner in repeated small arms trials, and was selected for adoption by the U.S. Navy in 1895 as the Lee Rifle, Model of 1895, caliber 6-mm, a.k.a. the M1895 Lee Navy.[7][9]

First contract

The first naval contract for the M1895 was let to Winchester for 10,000 rifles in January 1896 (serials 1–9999).[7][11] However, deliveries of the initial shipment of 10,000 rifles were not completed until 1897, owing to delays caused by manufacturing issues, as well as contract changes imposed by the navy.[12] The latter included a significant change in ammunition specification, which required extensive test firings followed by recalibration of the sights.[12]

Of the 10,000 rifles produced under the first contract, 1,800 were issued to the U.S. Marine Corps.[13] Marine battalions scheduled to be equipped with the 6 mm Lee rifle did not begin to receive their new rifles and ammunition until 1897, two years after adoption of the cartridge and rifle.[14] Colonel-Commandant Charles Heywood of the Marine Corps reportedly refused small initial allotments of the 6 mm Lee rifle to the Corps until he was given assurances that the Corps would be immediately issued at least 3,000 Lee rifles, improved target ranges, and most importantly, enough ammunition for Marine units to continue their existing marksmanship program.[15] Despite this threat, the September 1897 report of the Marine Corps Quartermaster to the Secretary of the Navy urgently requested a minimum additional $10,000 in funding to purchase sufficient 6 mm ammunition to allow Marines to conduct live fire and target practice with the Lee rifle.[16] The report warned that, except for drill practice, enlisted Marines were "entirely unfamiliar with the use of this arm", since all target practice still had to be conducted using the old single-shot Springfield and .45-70 black-powder ammunition.[16] Rifles with a serial number below 13390 (approx.) were made prior to December 31, 1898.[13] Additional smaller purchases were subsequently made to replace lost weapons, mostly in response to a fire at the New York Navy Yard which damaged or destroyed about 2,500 rifles; around 230 rifles were condemned as unrestorable. The additional small quantity purchases by the Navy as well as all sporting models fall into the 10000–15000 serial range, purchased between the two major contracts. Some confusion arises as to production dates for the sporting rifles as many of the commercially manufactured and numbered receivers (not USN marked) were not made into complete rifles until 1902, and sales continued until 1916. Military rifles have 28-inch (71-cm) barrels and navy anchor stamp, while rifles made for civilian sale have 24-inch (61-cm) barrels and no anchor.[13][17]

Second contract

A second contract was let on February 7, 1898 for an additional 5,000 rifles[13] at $18.75 each. This second contract (serials 15001 to 20000) began delivery in August 1898 and was completed in December 1898.

Reliability in the field

Overall, the Lee had a reputation for reliability in the field, though some issues were never overcome during the rifle's relatively short service life.[3] Beginning in 1898, during the Marine expeditionary campaign in Cuba, reports emerged from the field criticizing the floating extractor design.[3][18] The firing pin lock and bolt-lock actuator were relatively fragile, and would occasionally break or malfunction, while the tension in the en bloc cartridge clips proved difficult to regulate, occasionally causing failures to feed.[3][18][19]

Design and operation

Magazine system

The Lee's magazine system was improved over the prior navy rifle, the M1885 Remington-Lee, by incorporating a clip-loaded magazine system and an action capable of handling high-velocity, small-caliber smokeless cartridges. Designed by inventor James Paris Lee, the rifle weighed 8.3 pounds (3.7 kg) and was about 48 in (122 cm) long.[3] It was the first American military rifle to be loaded by charging an (optional) en bloc clip of five 6mm cartridges into the rifle magazine, similar to the Mannlicher clip system (except the Mannlicher required the clip to operate).[11] Lee later claimed in an unsuccessful lawsuit that his single-row clip-loaded magazine patent was infringed by von Mannlicher, but most historians agree that Mannlicher and Lee independently developed their en bloc magazine systems along separate but parallel lines.

After inserting the clip, it was then given a second push to ready the first round for chambering.[11] Closing the bolt stripped off each round in succession, feeding the next cartridge into the chamber. The clip itself dropped free from the magazine when the first cartridge had been loaded.[3][7][11] Unlike the M1892 Springfield (Krag) and the later M1903 Springfield rifle, the Lee straight-pull did not have a magazine cut-off to enable the cartridges in the magazine to be held in reserve in keeping with the prevailing small arms military doctrine of the day (for use in rapid-fire, close-range combat only, fed single rounds the rest of the time). The Chief of Ordnance considered the Lee clip to be superior to either the Mauser stripper clip or the Mannlicher en bloc clip, as cartridges were not required to be stripped from the clip into the magazine (like the Mauser 'stripper clip' system), yet the Lee clip was not an essential part of the magazine (like the Mannlicher system), since it dropped out after the first cartridge was loaded, and since single cartridges could be loaded into an empty or partially loaded magazine to replace cartridges fired (unlike the Mannlicher).[2][7] This conclusion was in conflict with the Naval Small Arms Board, which did consider the Lee clip to be an essential part of the magazine.[9]

When specifying the requirements for its new service rifle, the Navy emphasized that it desired a repeating rifle loaded by means of chargers or clips, but "since the conditions of service may require the use of loose cartridges, or may result in the disabling of the magazine, it is desirable that the small arm be susceptible of use as a single loader, and that the magazine be capable of being replenished by single cartridges.[9] The new Lee rifle and its magazine met all of these requirements, enabling a rifleman in an emergency to use the loose cartridges taken from loaded belts supplied to machine gun crews for the 6 mm Colt–Browning machine gun.[2][7]

Bolt mechanism

Along with the M1885 Remington-Lee and the M1892 Springfield, the M1895 Lee was one of the first infantry weapons adopted by U.S. forces to be equipped with a repeating action.[3] To operate the straight-pull mechanism, the operating handle is first pulled up at an angle to disengage the bolt and its wedge lock, then pulled sharply to the rear to extract and eject the spent case.[3] Pushing forward on the bolt handle strips a round from the magazine; as the bolt is slammed home, the bolt's wedge lock seats into place, the firing pin is cocked, and the fresh cartridge is seated in the chamber.[3] Once the M1895 is cocked, the rifle's bolt cannot be retracted unless the bolt-release lever is pushed downward.[3] This prevents opening of the action caused by an inadvertent bump or contact to the bolt handle. The rifle has a safety located on the top of the receiver, which is released by pushing down with the thumb on the safety button.[3]

Unlike many other military rifles of the day, the Lee was not fitted with a turning bolt.[3] Though frequently described as a straight-pull action, the M1895 Lee actually uses a camming action in which a steel wedge or locking block beneath the bolt is forced into a recessed area in the receiver.[3][20] Pulling the operating handle back causes the bolt to rock back and upwards, freeing a locking stud on the receiver and unlocking the bolt.[3] The firing pin cocked on final closing where the resistance would be overcome by the forward inertia of closing the action. Once the rather odd "up and back" bolt movement was mastered, and as long as the action was clean and well-lubricated, it worked fairly well, though the slightly inclined opening stroke proved awkward for some men when the rifle was operated from the shoulder.[3] Despite this, the Navy's Chief of Ordnance noted with approval that the Lee rifle could be fired "with great rapidity",[21] achieving a rate of fire considerably faster than most existing turn-bolt rifles of the day.[7][22]

Sights and other features

The M1895 was equipped with a ladder-type rear sight adjustable to a maximum of 2,000 yards, determined by actual firing at Winchester in March 1896.[12][23] Because of the relatively high velocity and flat trajectory of the 6mm Lee cartridge, authorities calibrated the sights at their lowest setting with a point-blank or dead aim range of 725 yards (663 m).[23][24] The latter was intended for use on targets at all ranges from point-blank to 700 yards.[23][24] The single battle setting was intended to discourage individual soldiers or marines from adjusting their sight elevation unless firing at mass targets at extreme ranges, in which case officers would give commands for ranges to be set in such situations. Owing to the necessity of supplying the Navy with rifles as soon as practicable, no provision for drift (windage) was included in the rear sight.[12] The prominence of the front sight and its exposure to damage led to the adoption of a sheet metal front sight cover for the 10,000 rifles in the original order.[12] The front sight cover was browned (blued) to reduce glare.[12] Each rifle was tested at Winchester for accuracy by firing a group of three shots at 50 yards, any rifle not showing the desired accuracy was returned to the line for adjustment, which sometimes involved restocking the entire rifle.[12]

The rifle was equipped with a firing-pin lock on the left side of the receiver, which acted as a safety. Pushing down on the slide-type lever unlocked the firing pin striker and made the weapon ready to fire.[11]

With its slim-contour 28-inch (710 mm) barrel, the rifle was slightly muzzle heavy. With practice it could be rapidly fired, recocked, and reloaded without taking the rifle from the shoulder. Contemporary reports and subsequent tests indicate that the M1895 and its ammunition were exceedingly accurate: target groups approaching a minute of angle at 100 yards were not unusual with individual rifles.[25] The M1895 was normally issued with a sling, bandoliers, and a modern 8.18-inch (208mm) knife-type bayonet. Individual sailors and marines were issued a black leather belt with adjustable cross suspenders, fitted with twelve black leather ammunition pouches.[15][26] The Lee Navy bayonet was the forerunner of short pattern bayonets still in use today.[27]

Ammunition

In December 1894, after a series of test evaluations with both rimmed and rimless 6mm cartridges, the U.S. Navy adopted the 6mm U.S.N. or 6mm Lee Navy cartridge.[2][9] It was the first U.S. military round to use a metric caliber in its official designation,[2] the first cartridge designed for use in both rifles and machine guns,[6] and the smallest-caliber cartridge to be adopted by any military power until the advent of the 5.56×45mm NATO cartridge in 1964.[28] The original 6mm ball loading was supplied by Winchester, and used a roundnosed, cupro-nickeled steel-jacketed lead-core bullet with a total weight of 135 grains.[2][29] In March 1897 a new military loading was adopted using a 112-grain (7.3 g) round-nose, copper-jacketed (FMJ) military loading developing 2,560 feet per second (780 m/s)[29][30] and 1,629 ft⋅lbf (2,209 J) of energy at the muzzle.[30][31] Besides providing increased velocity and a flatter trajectory, the primary reason for the change in cartridge and bullet design was to reduce chamber pressures and extend the life of the rifle barrel: the new 112-grain loading with its copper-jacketed bullet gave an average barrel life of 10,000 rounds as opposed to only 3,000 for the 135-grain steel-jacketed load.[12] Ordnance authorities specified a slightly slower rifling twist for the new loading – one turn in 7.5 inches (18 cm).[30] At some point during later production, this rifling was again changed to one turn in 10 inches RH (25 cm).[32]

The U.S. 6mm Lee Navy (6mm U.S.N.) cartridge used by the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps was initially supplied by Winchester Repeating Arms (WRA) and later, the Union Metallic Cartridge Company (UMC).[2] The rifle powder was Rifleite, a nitrocellulose flake powder supplied by a British company, the Smokeless Powder Co. Ltd.[4] The cartridge was semi-rimmed, and was designed to function in machine guns such as the M1895 Colt–Browning as well as in infantry rifles.[33] Intended for primarily for shipboard use against enemy naval forces in small boats, the 6mm Lee had considerably more penetrating power than the U.S. Army's .30 Army (.30-40 Krag) cartridge, and could perforate 23 inches (58 cm) of soft wood at 700 yards (640 m), a single 3/8 inch (9.5 mm) thick steel boiler plate at 100 feet (30 m), or a 0.276-in. (7 mm) plate of chromium steel (no backing) at 150 feet.[29][30]

Another advantage to the 6mm cartridge was in the reduced weight of the ammunition: 220 6mm cartridges weighed approximately the same as 160 cartridges in .30 Army caliber.[34] The basic combat ammunition load of an 1898 naval bluejacket or marine was 180 rounds of 6mm ammunition packed five-round clips, and carried in black leather ammunition pouches.[9][9][15][26][35][36][37] Outfitted in this manner, a navy bluejacket or marine could carry considerably more ammunition than that of the typical Army trooper of the day, who usually carried 100 rounds of .30 Army ammunition in individual cartridge loops on his Mills canvas cartridge belt.[15]

However, the 6mm U.S.N. cartridge may have been too advanced a concept for the technology of the day. The Navy experienced continued problems with the Rifleite smokeless powder used in the cartridge, which appears to have varied in consistency from lot to lot, while becoming unstable over time.[2][31] These problems were exacerbated by the custom of keeping ammunition aboard ship for long periods under conditions of high heat and humidity.[2][31] After some use, many Lee rifles developed bore and throat erosion,[23][31] and metal fouling due to unburned powder compounds, a problem intensified by substandard internal barrel finishing at the factory.[38] The M1895 Lee was also the only military rifle to use Metford rifling, which British authorities had discarded because of its tendency to wear too easily when used with the smokeless powders of the day.[2][39]

Naval and Marine service use

The M1895 Lee was carried aboard Navy ships for use by naval armed guards (bluejackets) and landing parties, and was the standard service rifle for enlisted Marines, both seaborne and guard forces. Fifty-four USN Lee rifles were recovered from the USS Maine, which was sunk in Havana harbor in 1898.[13][20][40] These were eventually sold to Bannerman's, a military surplus dealer.[20][40] Surviving examples seen of the confirmed Maine rifles have pitted receivers, which would be logical considering the salt water immersion in Havana Harbor.[40]

After the outbreak of the Spanish–American War, the M1895 was issued to marines of the First Marine Battalion aboard the naval transport USS Panther, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert W. Huntington.[36] As far as is known, all Marine companies involved in the Cuba combat operations were equipped with the 6mm Lee rifle. In addition to service with the First Battalion, additional rifles were later distributed by navy quartermasters to elements of free Cuban forces revolting against the Spanish government.[36][41] The Marine assault force had only just been issued their Lee rifles, and enlisted men aboard the Panther were hurriedly given lectures on operating and field-stripping their newly issued rifles aboard ship, along with ten 6mm rounds each to fire for familiarization purposes.[36][41][42] During a four-day call at Hampton Roads, Virginia, and later during a two-week stopover at Key West, Florida Lt. Col. Huntington ensured that all enlisted Marines aboard the USS Panther underwent target practice on the beaches with the Lee rifle, as well as marksmanship training and small-unit battle drills.[36][42] This last-minute opportunity for target practice and training proved fortuitous, as Cuban guerrillas later handed Lee rifles had some initial difficulty operating and using them, while Lt. Col. Huntington's Marines had no such problems.[36][42]

The first major combat use of the M1895 occurred during the land campaign to capture Guantánamo Bay, Cuba from June 9–14, 1898 with the First Marine Battalion, in particular at the battles of Camp McCalla and Cuzco Wells.[36][42] During the battle of Cuzco Wells, Marines using the M1895 Lee effectively engaged concentrations of Spanish troops at ranges up to 1,200 yards, using volley fire against groups of enemy soldiers while their officers called out the range settings.[36][41][42] Though some problems were noted with the new rifle,[18] the flat ballistics,[26] accuracy and rate of fire of the M1895 and the light weight of its 6mm ammunition proved to be of considerable benefit during offensive infantry operations over mountainous and jungled terrain against both Spanish regulars and loyalist guerrilla forces.[42] The extra cartridges proved useful when early ammunition resupply from Navy ships was disrupted at the outset of the Guantanamo operation, allowing Marines to continue their assault even while individually resupplying Cuban rebels who had run short of ammunition.[43] After the battle of Cuzco Wells, the surviving members of the retreating Spanish garrison informed the Spanish General Pareja at Ciudad Guantánamo that they had been attacked by 10,000 Americans.[44]

The M1895 would see considerable action in the Pacific during the Spanish–American War and the early stages of the later Philippine–American War with U.S. Navy and Marine personnel. During the Moro Rebellion of 1899–1913, it was reported that some Marines preferred the M1892/98 Springfield (Krag) rifle and its .30-caliber ammunition to the M1895 Lee Navy and its 6mm U.S.N. cartridge, believing the latter to have inadequate shocking or stopping power against frenzied bolo-wielding Moro juramentados, who attacked from jungle cover at extremely close distances.[45][46] In this situation, the 6mm Lee bullet may have overpenetrated without causing sufficient shock and trauma to the enemy, a situation which the Chief of the Bureau of Naval Ordnance had foreseen as early as 1895, when he acknowledged the concern that "the wounds produced by small-caliber bullets will frequently not be sufficient to put the wounded out of action and their shock will not stop the onset of excited men at short range".[7][47][48] On the other hand, the Marine Legation Guard, which used the 6mm U.S.N. cartridge in the defense of the foreign legations in Peking during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, apparently had no such criticisms.[49] U.S. forces equipped with the Lee rifle in the first (Seymour) relief expedition advancing from Tientsin to relieve the Marines at Peking were able to transport some 10,000 rounds of 6mm ball for the riflemen as well as a Colt machine gun crew, and consequently never ran short of ammunition, unlike other Western forces, who were forced to capture the Imperial Chinese arsenal at Hsiku to find enough cartridges to continue fighting.[50] During the same expedition, Marine sharpshooters using the Lee Navy rifle managed to eliminate the gun crews of two heavy artillery batteries using only rifle fire.[50]

However, the service life of the M1895 as a first-line infantry weapon was soon to end. In December 1898, a board of officers from the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps recommended that all services adopt the .30 Army cartridge and the small arms and machine guns chambered for it.[31][51][52] The board did acknowledge that the rimmed .30 Army round was less than ideal when used in modern machine guns, and that the decision to adopt the .30 Army for the Navy and Marine Corps might be postponed until a rimless version of the .30 Army had been developed.[52] The board's recommendations were later adopted by the War Department.

In the end, the Navy and Marine Corps decided not to wait. As early as November 1899, the Navy placed its first contract for 1,000 Model 1892/98 "U.S. Army magazine rifles" in .30 Army (.30-40 Krag) caliber,[31] with the first M1892/98 rifles issued to the newest pre-dreadnought battleships Kearsarge and Kentucky. New contracts for M1892/98 rifles were let as the U.S. Navy continued to expand, though the M1895 Lee and its 6mm cartridge would continue to see service aboard Navy vessels well into the turn of the century.[53] The U.S. Marines continued to use the M1895 Lee rifle until January 1900, when they received Model 1892/98 rifles in exchange (Philippines and Far East Marine battalions were the first to receive the new rifle and ammunition).[54] The Navy continued to use the M1895 Lee as its primary small arm through at least 1903.[53] From 1910 to 1911, both the M1895 Lee and the M1892/98 "Krag" service rifles were supplanted in Navy and Marine Corps service by the new M1903 Springfield rifle in .30-06 caliber,[13][55] though the M1895 Lee would remain in service aboard some ships of the fleet into the 1920s, albeit as a secondary (drill practice) arm.

See also

- James Paris Lee – The designer of the M1895

- Lee–Enfield – Another rifle designed in part by James Paris Lee

- List of individual weapons of the U.S. Armed Forces

- M1903 Springfield – The M1895's replacement

- Mannlicher M1895 – An Austrian straight-pull bolt-action rifle

- Ross rifle – An ill-fated Canadian straight-pull bolt-action rifle

- Schmidt–Rubin – A Swiss straight-pull bolt-action rifle

References

- Barnes, Frank C., ed. by John T. Amber, Cartridges of the World: 6mm Lee Navy (6th ed.), Northfield, IL: DBI Books Inc., ISBN 0-87349-033-9 (1984), p. 102

- Hanson, Jim, The 6mm U.S.N. - Ahead Of Its Time, Rifle Magazine Vol. 9 No. 1 (January–February 1977), pp. 38–41

- Walter, John, The Rifle Story: An Illustrated History from 1776 to the Present Day, MBI Publishing Company, ISBN 1-85367-690-X, 9781853676901 (2006), pp. 133–135

- Reports of Companies, The Chemical Trade Journal and Oil, Paint, and Colour Review, Vol. 18, June 20, 1896, p. 401: The Smokeless Powder Co., Ltd. originally developed Rifleite for the British .303 cartridge.

- Walke, Willoughby (Lt.), Lectures on Explosives: A Course of Lectures Prepared Especially as a Manual and Guide in the Laboratory of the U.S. Artillery School, J. Wiley & Sons (1897) p. 343: Rifleite was a flake smokeless powder composed of soluble and insoluble nitrocellulose, phenyl amidazobense, and volatiles similar to French smokeless powders; unlike cordite, Rifleite contained no nitroglycerine.

- The New York World, The World Almanac and Encyclopedia: Rifles Used by the Principal Powers of the World, Vol. 1 No. 4, New York: Press Publishing Co. (January 1894), p. 309: The Naval Small Arms Board reported that in adopting the 6mm cartridge specification, "due consideration has been given to the desirability of using the same cartridge for machine guns as for the small arm, and the Board deems that no difficulty in the manufacture or manipulation of machine guns will be caused by their use of 6mm ammunition."

- Sampson, W.T., The Annual Reports of the Navy Department: Report of Chief of Bureau of Ordnance, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1895), pp. 215–218

- Sampson, W.T., Annual Reports of the Navy Department: Report of Chief of Bureau of Ordnance, Notice to Inventors and Others, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1894), pp. 385–388

- The Annual Reports of the Navy Department: Report of the Secretary of the Navy – Report of Naval Small Arms Board, October 22, 1894, November 22, 1894, and May 15, 1895, Washington, D.C.: United States Navy Dept. (1895), pp. 301–310

- Walter, John, Rifles of the World (3d ed.), Krause Publications, ISBN 0-89689-241-7, ISBN 978-0-89689-241-5 (2006), p. 568: The Model 1893/94 Luger Rifle was an experimental design derived from the German Gewehr 88 service rifle, and was equipped with a magazine that would accept stripper clips, Mannlicher clips, or Luger clips.

- Henshaw, Thomas, The History of Winchester Firearms 1866–1992 (6th ed.), Academic Learning Company LLC, ISBN 0-8329-0503-8, ISBN 978-0-8329-0503-2 (1993), pp. 47–48

- Dept. of the Navy, The Annual Reports of the Navy Department: Report of the Secretary of the Navy, Washington, D.C.: United States Navy Dept. (1897), pp. 321–323

- Flayderman, Norm, Flayderman's Guide to Antique American Firearms and Their Values (9th ed.), F + W Media, Inc., ISBN 0-89689-455-X, 9780896894556 (2007), pp. 319–320

- Heywood, Charles (Col. Commandant), Annual Reports of the Navy, Report of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1897) pp. 558–559

- Hearn, Chester G., Illustrated Directory of the United States Marine Corps, Zenith Imprint Press, ISBN 0-7603-1556-6, ISBN 978-0-7603-1556-9 (2003), pp. 74, 78–79

- Denny, F.L., The Annual Reports of the Navy Department, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, U.S. Marine Corps Quartermaster Estimates, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1897), pp. 572–573

- Schreier, Philip American Rifleman (May 2008) p.104

- Reid, George C. (Maj.), The Annual Reports of the Navy Department, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, Report of Inspection of the Marine Battalion at Camp Heywood, Seaveys Island, Portsmouth, N.H., September 14, 1898: Arms, Vol. 3753, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1898), pp. 847–849: Some rifles were not yet sighted in for the new 112-grain loading, while others suffered broken extractor springs, triggers, and followers. The breechblock stop could be misplaced while cleaning, resulting in the loss of the extractor and spring. As the extractor was not pinned to the bolt, it could and did occasionally fall out and become lost when the bolt release catch was pressed and the bolt either fell out or was removed for cleaning. The floating extractor was a regular source of trouble throughout the Lee's short service life.

- Dept. of the Navy, The Annual Reports of the Navy Department: Report of Naval Board on Small Arms, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1895), pp. 308–309

- Sterett, Larry S., Straight-Pull Rifles, The American Rifleman, Vol. 5, Issue 2 (February 1957), pp. 30–32

- Sampson, W.T., The Annual Reports of the Navy Department, Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, October 1, 1895: Small Arms, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1895), p. 215-216: Using a seaman unfamiliar with the Lee rifle, and starting with loaded magazine and empty chamber, with the rifle at the shoulder and roughly aimed, the seaman was able to fire five shots in three seconds, and from 63 to 71 shots in two minutes using the five-round Lee clips.

- Crossman, Edward C., The Rifle of the Hun, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 30, No. 2 (1918), p. 186: The M1895 Lee's rate of fire with its straight-pull action and charger loading was faster than most bolt-action rifles such as the M1898 Mauser, which had a rate of fire of five shots in eight seconds using a trained rifleman.

- Mullin, Timothy J., Testing the War Weapons, Boulder, CO: Presidio Press, ISBN 0-87364-943-5 (1997), pp. 332–333

- Keeler, Bronson C., The Sentinel Almanac and Book of Facts, Vol. I, No. 1, The Milwaukee Sentinel Co. (1896) p. 139

- James, Garry, Classic Test Report: Lee Navy rifle 6mm, Guns & Ammo (July 1985): A 1.5" group of five shots fired at 100 yards was recorded in a 90-year-old M1895 Lee rifle.

- Reid, George C. (Maj.), The Annual Reports of the Navy Department, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, Report of Inspection of the Marine Battalion at Camp Heywood, Seaveys Island, Portsmouth, N.H., September 14, 1898: Accouterments [sic], Vol. 3753, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1898), pp. 847–849: At Guantanamo, the Marines carried 180 rounds (36 chargers or clips) of 6mm ammunition in black leather pouches attached to their service belts.

- Canfield, Bruce N. 19th Century Military Winchesters March 2001 American Rifleman p.40

- Johnson (Jr.), Melvin Maynard and Haven, Charles T., Ammunition: its History, Development and Use, 1600 to 1943 -.22 BB cap to 20 mm. shell, New York: William Murrow & Co. (1943), p. 100

- Beyer, Henry G., Observations On The Effects Produced By The 6-mm Rifle and Projectile, Vol. 3, Boston Medical Journal, Boston Society of Medical Sciences (1899), pp. 117–136

- Sharpe, Philip B., The Rifle In America (2nd ed.), New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co. (1947), pp. 235–236

- Newton, Charles, Outing, Ballistics of Cartridges: Military Rifles III, Outing Publishing Co. Vol. 62 (1913), pp. 370–372

- Mann, Franklin W. (Dr.), The Bullet's Flight From Powder to Target: The Internal and External ballistics of Small Arms, New York:Munn & Co. Publishers (1909), p. 303

- The New York World, The World Almanac and Encyclopedia: Rifles Used by the Principal Powers of the World, Vol. 1 No. 4, New York: Press Publishing Co. (January 1894), p. 309

- Sage, William H. (Maj.), and Clark, H.C. (Capt.) (ed.), Journal of the United States Infantry Association, Washington, D.C.: United States Infantry Association, Vol. IV, No. 4 (January 1908), p. 520

- Converse, George A. (Commander) et al, The Annual Reports of the Navy Department, Annual Report to the Secretary of the Navy: Report of Naval Small Arms Board, May 15, 1895, Washington, D.C.: United States Navy Dept. (1895), p. 309: The Navy originally planned to use disposable ammunition boxes attached to the seaman's leather service belt, to be constructed of light metal or paper/wood composites, and packed with 160 rounds (eight 5-round chargers per box); this idea was later dropped in favor of conventional black leather ammunition pouches.

- Daugherty, Leo J., Pioneers of Amphibious Warfare, 1898–1945: profiles of fourteen American Military Strategists, McFarland Press, ISBN 0-7864-3394-9, ISBN 978-0-7864-3394-0 (2009), pp. 22–27

- U.S. Marine in 1900 Period Uniform Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Navy 1895 Winchester-Lee Rifle, retrieved 14 November 2011

- Metcalf, V.H., Report of Small Arms Target Practice: Report of the Captain of the Navy Rifle Team, Leavenworth, Kansas, September 6, 1908, Navy Dept., Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1908), p. 38

- Seton-Karr, Henry (Sir), Rifle, Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Co., Vol. 23 (Ref – Sai), (1911), p. 327

- Relics Recovered From the USS Maine Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 15 November 2011

- Millett, Alan R., Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps, New York: Simon and Schuster Inc., ISBN 0-02-921596-X, 9780029215968 (1991), pp. 131–133

- Keeler, Frank and Tyson, Carolyn A. (ed.), The Journal of Frank Keeler, 1898, Washington, D.C.: Marine Corps Letters Series, No. 1, Training and Education Command, (1967), p. 14, 18, 33, 38, 46

- Keeler, Frank and Tyson, Carolyn A. (ed.), The Journal of Frank Keeler, 1898: Appendix: Report of Captain G.F. Elliott, USMC, Washington, D.C.: Marine Corps Letters Series, No. 1, Training and Education Command, (1967), p. 46: "The marines fired on average around 60 shots each, the Cubans' belts being refilled during the action from the belts of the marines, each having to furnish 6 clips or 30 cartridges."

- Reynolds, Bradley M., New Aspects of Naval History: Selected Papers From the 5th Naval History Symposium, U.S. Naval Academy, Nautical and Aviation Publishing Co. of America, ISBN 0-933852-51-7, ISBN 978-0-933852-51-8 (1985), p. 147

- Alexander, Joseph H., Horan, Don, and Stahl, Norman C., Battle History of the U.S. Marines: A Fellowship of Valor, New York: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-093109-4, ISBN 978-0-06-093109-4 (1999), p. 24

- Arnold, James R., The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902–1913, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, ISBN 1-60819-024-2, ISBN 978-1-60819-024-9 (2011), p. 95

- Heinl, Robert D., Soldiers of the Sea: The United States Marine Corps, 1775–1962, Nautical & Aviation Pub Co of America, ISBN 1-877853-01-1, ISBN 978-1-877853-01-2 (1991), p. 189

- Dieffenbach, A.C., (Lt.) Dept. of the Navy, The Annual Reports of the Navy Department: Report of the Secretary of the Navy – Report on the Manufacture and Inspection of Ordnance Material, Washington, D.C.: United States Navy Dept. (1897), pp. 321–323

- Simmons, Edward H. and Moskin, J. Robert,The Marine, Hong Kong: Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, Hugh Lauter Levin Associates Inc., ISBN 0-88363-198-9 (1998), p. 158

- Wurtsbaugh, Daniel (Lt.), The Seymour Relief Expedition, Washington, D.C.: Naval Institute Proceedings, United States Naval Institute (1902), pp. 207, 218

- Annual Reports of the Secretary of the Navy: Report of the Chief of Ordnance, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 26

- Mordecai, A. (Col.), "U.S. House of Representatives, Annual Reports of the War Department For the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1899: Proceedings of a Board of Officers of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, December 8, 1898, Appendix 49, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, (1899), pp. 531–532

- United States Congress, The Story of Panama: Excerpts From the Log Book of the USS Dixie, Rep. Henry D. Flood, Chairman, Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 434: As late as October 1903, ships at the New York Navy Yard were still receiving ordnance stores of "Ball Cartridge, 6mm" in amounts outnumbering that of .30 caliber ammunition.

- Root, Elihu, Elihu Root Collection of United States Documents: Report of the Commandant of the United States Marine Corps, United States Magazine Rifles, Caliber .30, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (September 29, 1900), pp. 1096–1097

- McCawley, Charles L. (Lt. Col.), Hearings Before Committee on Naval Affairs of the House of Representatives: Testimony of Lt. Col. Charles L. McCawley, Afternoon Session, December 7, 1910, Committee on Naval Affairs, House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1911) pp. 202–203

Further reading

- Myszkowki, Eugene (1999). The Winchester-Lee Rifle. Tucson, Arizona: Excalibur Publications. ISBN 978-1-880677-15-5.

- United States. Bureau of Naval Personnel; John Jacob Hunker (1900). Manual of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery for the U.S. Naval Training Service. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 17.

- Cyrus S. Radford (1898). Hand-book on Naval Gunnery. D. Van Nostrand Company. p. 215.

- United States. Navy Dept (1897). Annual Reports of the Navy Department: Report of the Secretary of the Navy. Miscellaneous reports. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 321.