Ludwig Knorr

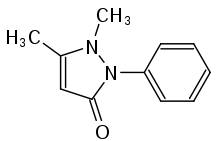

Ludwig Knorr (2 December 1859 – 4 June 1921) was a German chemist. Together with Carl Paal, he discovered the Paal–Knorr synthesis, and the Knorr quinoline synthesis and Knorr pyrrole synthesis are also named after him. The synthesis in 1883 of the analgesic drug antipyrine, now called phenazone, was a commercial success. Antipyrine was the first synthetic drug and the most widely used drug until it was replaced by Aspirin in the early 20th century.[1]

Ludwig Knorr | |

|---|---|

-Grab_in_M%C3%BCnchen.jpg) Grave yard at "Alter Südfriedhof" in Munich/Germany | |

| Born | 2 December 1859 |

| Died | 4 June 1921 (aged 61) Jena, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Erlangen |

| Known for | synthesis of Phenazone Paal-Knorr synthesis Knorr quinoline synthesis Knorr pyrrole synthesis |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | University of Jena |

| Doctoral advisor | Hermann Emil Fischer |

Early life

Ludwig Knorr was born to the wealthy merchant family in 1859. He grew up in the Sabbadini-Knorr company headquarters, located in the Kaufingerstraße in the center of Munich, and in the family house near the Lake Starnberg. After the early death of his father, the education of him and his four brothers lay in the hands of their mother. In 1878 Knorr received his Abitur and started to study chemistry at the University of Munich.[2][3]

In the beginning, he studied under Jacob Volhard; then, after Volhard left for the University of Erlangen, Hermann Emil Fischer became his tutor. In the summer of 1880 Knorr worked with Robert Wilhelm Bunsen at the University of Heidelberg, and later assisted Adolf von Baeyer in Munich. When Emil Fischer became professor at the University of Erlangen, he asked Knorr to follow him.[2][3]

University of Erlangen

In 1882 Knorr received his PhD for a thesis titled Über das Piperyl-Hydrazin. His habilitation followed three years later in 1885 with a thesis titled Über die Bildung von Kohlenstoff-Stickstoff-Ringen durch Ein-wirkung von Amin-und Hydrazinbasen auf Acetessigester und seine Derivate ("On the formation of carbon-nitrogen rings through the action of amine and hydrazine bases on acetoacetate and its derivatives"). In that time, during his search for quinine related compounds, Knorr discovered the unmethylated Phenazone. As another quinine-related compound kairin showed analgesic and antipyretic properties, Knorr and Fisher asked Wilhelm Filehne at the Hoechst company to check the unmethylated and the methylated phenazone for its pharmacological properties. Knorr patented the compound in 1883. Filehne later suggested the names Höchstin or Knorrin for the substance but Knorr telegraphed from his honeymoon that his variant of the name, antipyrine, is not to be changed. (German: Antipyrin bleibt!).[4] In 1885 Knorr married Elisabeth Piloty, the sister of his laboratory colleague Oskar Piloty at the University of Munich.[2]

University of Würzburg

In 1885 Fischer became professor at the University of Würzburg and Knorr followed him and was made associate professor. Knorr described the time in Würzburg as most untroubled and most productive period of his life. Reactions of ethyl acetoacetate with numerous other compounds were the main focus of his work there. After the death of Johann Georg Anton Geuther in 1889, the University of Jena was searching for a new full professor and Ernst Haeckel was sent to Würzburg to evaluate whether Knorr was qualified for the position.[2]

University of Jena

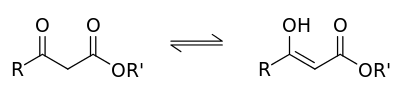

Knorr became full professor at the University of Jena in 1889. In the following two years, he planned and built a new laboratory suitable for his research. His focus gradually shifted from the structure of pyrazoles to the more general concept of tautomerism. In collaboration with various other chemists, Knorr proved the concept that ethyl acetoacetate existed in a keto and an enol forms. In his later years, the structural conformation of morphine became his main point of interest. During the World War I, Knorr served in the medical corps and returned to the University of Jena after the war ended. Knorr died after a short illness on 4 June 1921.[2]

References

- Walter Sneader. (2005). "Plant Product Analogues and Compounds derived from Them". Drug discovery: a history. Chichester: Wiley. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- "Ludwig Knorr. zum Gedächtnis (1859-1921)". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 60 (1): A1–A34. 1921. doi:10.1002/cber.19270600155.

- Duden (1921). "Ludwig Knorr". Zeitschrift für Angewandte Chemie. 34 (48): 269. doi:10.1002/ange.19210344802.

- Brune, K (1997). "The early history of non-opioid analgesics". Acute Pain. 1: 33–40. doi:10.1016/S1366-0071(97)80033-2.

External links

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.