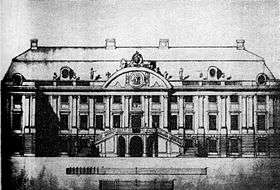

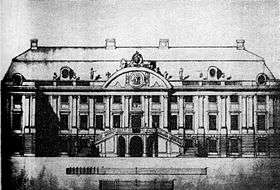

Lubomirski Palace (Opole Lubelskie)

The Lubomirski Palace (pl:Pałac Lubomirskich) in Opole Lubelskie, Lublin Voivodship, Poland (formerly the Slupecki Palace - pl:Pałac Słupeckich), is a much-altered 18th-century palace formerly belonging to the Słupecki and Lubomirski families.

| Lubomirski Palace | |

|---|---|

Pałac Lubomirskich | |

Designs for the palace c1770, before it was heavily altered c1850 | |

Location within Poland | |

| Former names | Slupecki Palace (Słupeckich Pałac) |

| General information | |

| Type | Palace |

| Architectural style | Baroque |

| Location | Opole Lubelskie |

| Country | Poland |

| Coordinates | 51°09′03″N 21°58′32″E |

| Construction started | 1737 |

| Completed | 1773 |

| Client | Antoni Lubomirski |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 3 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Domenico Merlini |

From the 16th century onwards the palace housed a growing collection of books - many of them theological - and also a collection of fine art paintings. The library and pictures were dispersed in the mid-nineteenth century, when ownership of the palace passed to the Russian tsarist government. The building was stripped of its baroque architectural features and used as a military barracks and hospital. It currently houses a high school named for Adam Mickiewicz.

Description

The present form of the palace is a reconstructed barracks, carried out after 1854. The earlier reconstructions have been obliterated. Today it is a large, three-storey building on a rectangular plan with prominent projections at the ends of the façade. The interior layout is two-bay, partly changed during the subsequent reconstructions and repairs. The interior décor has not survived. In the basement the vaults are preserved, with lunettes and barrel vaulting. The northern façade looking over the courtyard has thirteen bays, separated by pilasters with Ionic capitals (finials). The middle window (slightly wider than the others) on the first floor of the façade is a remnant of the eighteenth century main entrance door, approached by flights of stone steps. The south elevation - formerly overlooking the formal garden has fifteen bays with pilasters, but with Tuscan capitals. The ground floor is rusticated, creating a base for the building.[1]

There have been no archaeological excavations, and little is known about the former buildings which used to form a courtyard around the palace. Only an outbuilding to the south-east survives, which was turned into a hospital. It was one of Four buildings built in the eighteenth century to form a surrounding courtyard. On the foundations of outbuildings to the south-west one of the hospital buildings rises. There are no traces left of the northern outbuildings - the north-western one was demolished in 1996, the north-eastern much earlier. To the west of the palace a few old buildings the farm remain; and the granary from the late eighteenth century was converted into a cinema. A field hospital, built in the second half of the nineteenth century by the tsarist army and located south of the palace, was demolished in 2001. Also preserved is an eighteenth-century statue of St. John of Nepomuk, now in the hospital; it probably originally stood on a circular island in the ornamental pond on the north side of the palace.[1]

History

Słupecki family

A medieval castle with a moat formerly stood on the site, which was further surrounded by ponds including a fish pond on the eastern side. Sięgniew Słupczy was the owner of Opole in 1368. Opole was granted civic rights at the end of the fourteenth century, perhaps coinciding with the construction of the castle. The exact date is not known - documents were burned in the fifteenth century. King Casimir IV of Poland renewed the privilege in the years 1450 and 1478. The influence of the Słupecki family increased through the sixteenth century, and Stanislaw Słupecki, Castellan of Lublin, began collecting fine art paintings, and a large library.[1]

Work on the reconstruction of the medieval mansion into the modern Opole palace began not long after 1600, when Felix Słupecki (c1571-1616), Castellan of Lublin, and Barbara Leszczynski—the sister of Rafal Leszczynski of Baranow Sandomierski—were married in the Baranowski mansion.[1] The building was finished by 1613 - the date is testified on a ceiling beam rediscovered during the renovation in the 1930s. The beam is now located in the old bell tower at the parish church in Opole. There are no other surviving remains of the old medieval building. It is possible that reconstruction was carried out by Santi Gucci from the court of Jan III Sobieski, who designed of reconstructions of castles in Janowiec and Baranow, both associated with related with Firleja and Słupecki families and Rafal Leszczynski.[1]

Felix Słupecki was a Calvinist, unlike the majority of Poles who were Catholic (see Religion in Poland) although, and members of his family studied in Nuremberg, Heidelberg, Strasbourg, Basel and Leiden, rather than, for example, the University of Padua favoured by other Poles.[1][2] The Słupeckis maintained lively contacts with Western European thinkers and hosted many of them in Opole. From the sources it is known among others that Felix Słupecki corresponded with the Dutch Protestant jurist Hugo de Groot (Grotius) who, as an Arminian, was involved on the other side of the Calvinist–Arminian debate. Słupecki's extensive library contained a number of theological works, and he founded a Reformed Church school in Opole Lubelskie in 1598, with Krzysztof Kraiński as its first head.[3] George Słupecki, the last male descendant of the family, died in 1664. Opole passed into the hands of the Anglo-Irish-German pl:Butler family, the Dunin-Borkowski, and then Tarłó families by about 1690.[1]

The palace was rebuilt in the Baroque style in the years 1737-1743 for Jan Tarło, the voivode of Lublin Voivodeship, under the direction of Tylman of Gameren, the architect of the court in Puławy. The contract committed him to "transform the old palace in Opole and new pavilions at the corners, with stonemasons."[1] Jan Tarło brought the Order of Piarists to Opole in 1743, a still-existing educational Catholic order. The Piarists opened the first vocational school of craft in Poland in 1761 in Opole, based on modern principles of teaching. Many books from the house were given to the seminary when the great library was dispersed in the 19th century. The Piarists were ejected from Opole after the January Uprising in 1863.

Jan Tarłó's widow, Sophia Krasinski Lubomirska, created a park around the palace and continued to enlarge the library and art collection.[4]

Lubomirski family

The house was acquired in 1754 by Prince Antoni Lubomirski, and remodelled between 1766 and 1773 by (among others) Domenico Merlini and the royal architect, Jacob Fontana.[6][7]

The palace was inherited in 1782 by his nephew Prince Alexander Lubomirski, who wanted to create a cultural residential park similar to the Czartoryski palace in Puławy (the 'Polish Athens') a few miles away.[6] Alexander Lubomirski also built a Palladian villa for entertaining guests in Niezdowie, about 1 km west of the palace, in 1785-1787.[5]

He married Rozalia Czartoryski, and they had a daughter Princess Alexandra Francis Lubomirska. Rozalia was in Paris (with Alexandra, aged 7) during the Reign of Terror. She was arrested several times in Paris on espionage charges and was guillotined in 1794 aged 23. Alexandra was freed from the same prison where she had been held with her late mother, and returned to Opole.

However, Polish discontent after the Second Partition of Poland in 1793 led to the Kościuszko Uprising of 1794. The Russians quelled the uprising, and after the Third Partition of Poland, Poland ceased to exist as a country for 123 years.[8] The nearby palace in Puławy belonging to Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski was plundered utterly and burnt by the Russians for his part in the uprising.[9]

Alexandra's tutor in Opole around 1800 was Jean Vesque de Puttelange, an exiled former government official from the Habsburg Netherlands; his son Johann Vesque von Püttlingen (the composer 'J. van Hoven') was born in the palace. In 1804 she and her father moved to Habsburg-ruled Vienna where she married the orientalist, Count "Emir" Wacław Seweryn Rzewuski.

19th century military use

In 1847, Alexandra Rzewuska sold the Niezdowie grand villa to a judge, Kazimierz Wydrychiewicz.[5][10] In 1854 she disposed of (or sold) the house and its contents to the Russian general Ivan Paskyévich, the Namestnik of the Kingdom of Poland since 1831. Many of the books in the library were donated to the Piarist seminary in Opole; after the Order was suppressed after the January Uprising, some of the collection ended up in the Hieronim Łopaciński public library in Lublin.

After 1854 the Lubomirski palace was converted into a Russian military barracks, undergoing a severe redesign which included the loss of the mansard roof and the removal of the balustrades and tympanums; the third storey was heightened. The outbuildings were turned into a hospital, the last being demolished c2001. The former interior décor no longer survives.

Further rebuilding took place in the 1940s and 1960s. The Lubomirski palace is currently used as a high school named after the national poet of Poland, Adam Mickiewicz.

References

- Notes

- Citations

- Macík, Hubert (2008). "Opole Lubielskie". Zamki Polskie (in Polish). Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Berger, Teresa (2012). Liturgy in Migration: From the Upper Room to Cyberspace. Liturgical Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780814662755.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berger 2012, p. 111.

- "History of Opole Lubelskie". opolelubelskie.pl. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- Sołtys, Angela (2001). "Aleksander Lubomirski's villa in Niezdów". Kwartalnik Architektury i Urbanistyki 4/2001. (Architectural and Town Planning Quarterly, abstract in English). BazTech. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- "Pałac Lubomirskich w Opolu Lubelskim" (in Polish). Atlas Rezydencji. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- Salter, Mark; Bousfield, Jonathan. (2000). Poland. Rough Guides. p. 312. ISBN 1858288495.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Peter Hagget. "Encyclopedia of World Geography, Volume 24" Marshall Cavendish, 2001. ISBN 0761472894. p 1740

- Michelet, Jules (1968). Cadot, Michel (ed.). Legendes Democratiques du nord (in French). Presses Universitaires de France. p. 63. The remainder of the Polish nobility in the Russian-ruled parts of Poland who supported the uprising were stripped of their possessions and estates, which were in turn awarded to Russian generals and favourites of the St Petersburg court.

- Died 1869. Photo of gravestone in Opole. "Ś.P. Kazimierz Wydrychiewicz Właściciel Opolszczyzny +1869". Panoramio. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

Further reading

- Gawarecki, Henryk. O pałacu w Opolu po raz trzeci. Przebudowa pałacu przez Franciszka Magiera około 1740 roku. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki t. XXIV

- Katalog Zabytków Sztuki w Polsce t. VIII, Województwo lubelskie

- Rolska-Boruch, Irena. Pałac w Opolu, jego dzieje i zbiory. Roczniki Humanistyczne t. XLVII

- Rolska-Boruch, Irena. Siedziby szlacheckie i magnackie na ziemiach zwanych Lubelszczyzną. 1500-1700

- Rolska-Boruch, Irena. Domy pańskie na Lubelszczyźnie od późnego gotyku do wczesnego baroku

- Tatarkiewicz, Władysław. Opole i Nałęczów – Merlini i Nax. O sztuce polskiej XVII i XVIII wieku

- Teodorowicz-Czerepińska, Jadwiga (1969). Ponownie o pałacu w Opolu. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki t. XXII