Lu Ji (Shiheng)

Lu Ji (261–303), courtesy name Shiheng, was a writer and literary critic who lived during the late Three Kingdoms period and Jin dynasty of China. He was the fourth son of Lu Kang, a general of the state of Eastern Wu in the Three Kingdoms period, and a grandson of Lu Xun, a prominent general and statesman who served as the third Imperial Chancellor of Eastern Wu.

Lu Ji 陸機 | |

|---|---|

| Born | Family name: Lu (陸) Given name: Ji (機) Courtesy name: Shiheng (士衡) 261 |

| Died | 303 (aged 42) |

| Occupation | Writer, literary critic |

| Notable works |

|

| Relatives | |

Life

Lu Ji was related to the imperial family of the state of Eastern Wu. He was the fourth son of the general Lu Kang, who was a maternal grandson of Sun Ce, the elder brother and predecessor of Eastern Wu's founding emperor, Sun Quan. His paternal grandfather, Lu Xun, was a prominent general and statesman who served as the third Imperial Chancellor of Eastern Wu. After the Jin dynasty conquered Eastern Wu in 280, Lu Ji, along with his brother Lu Yun, moved to the Jin imperial capital, Luoyang. He served as a writer under the Jin government and was appointed president of the imperial academy. "He was too scintillating for the comfort of his jealous contemporaries; in 303 he, along with his two brothers and two sons, was put to death on a false charge of high treason."[1]

Writings

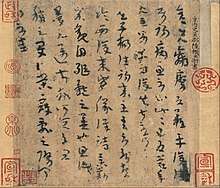

Lu Ji wrote much lyric poetry but is better known for writing fu, a mixture of prose and poetry. He is best remembered for the Wen fu (文賦; On Literature), a piece of literary criticism that discourses on the principles of composition. Achilles Fang commented:

The Wen-fu is considered one of the most articulate treatises on Chinese poetics. The extent of its influence in Chinese literary history is equaled only by that of the sixth-century The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons of Liu Hsieh. In the original, the Wen-fu is rhymed, but does not employ regular rhythmic patterns: hence the term "rhymeprose."[2]

The first translation into English is by Chen Shixiang, who translated it into verse because, although the piece was rightly called the beginning of Chinese literary criticism, Lu Zhi wrote it as poetry.[3]

Notes

- Weinberger, Eliot, ed. (2003). The New Directions Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry. New Directions. p. 240. ISBN 0-8112-1540-7.

- Weinberger, Eliot, ed. (2003). The New Directions Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry. New Directions. p. 241. ISBN 0-8112-1540-7.

- Lu, 1952 & p. vii.

References

- 2005 Encyclopædia Britannica, copyrighted 1994-2005

- Li, Siyong and Wei, Fengjuan, "Li Ji". Encyclopedia of China (Chinese Literature Edition), 1st ed.

- Lu, Ji (1952). Essay on Literature. Translated by Chen, Shixiang. Portland, Me.: Anthoensen Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)