Lowest common ancestor

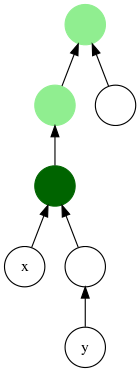

In graph theory and computer science, the lowest common ancestor (LCA) of two nodes v and w in a tree or directed acyclic graph (DAG) T is the lowest (i.e. deepest) node that has both v and w as descendants, where we define each node to be a descendant of itself (so if v has a direct connection from w, w is the lowest common ancestor).

The LCA of v and w in T is the shared ancestor of v and w that is located farthest from the root. Computation of lowest common ancestors may be useful, for instance, as part of a procedure for determining the distance between pairs of nodes in a tree: the distance from v to w can be computed as the distance from the root to v, plus the distance from the root to w, minus twice the distance from the root to their lowest common ancestor (Djidjev, Pantziou & Zaroliagis 1991). In ontologies, the lowest common ancestor is also known as the least common ancestor.

In a tree data structure where each node points to its parent, the lowest common ancestor can be easily determined by finding the first intersection of the paths from v and w to the root. In general, the computational time required for this algorithm is O(h) where h is the height of the tree (length of longest path from a leaf to the root). However, there exist several algorithms for processing trees so that lowest common ancestors may be found more quickly. Tarjan's off-line lowest common ancestors algorithm, for example, preprocesses a tree in linear time to provide constant-time LCA queries. In general DAGs, similar algorithms exist, but with super-linear complexity.

History

The lowest common ancestor problem was defined by Alfred Aho, John Hopcroft, and Jeffrey Ullman (1973), but Dov Harel and Robert Tarjan (1984) were the first to develop an optimally efficient lowest common ancestor data structure. Their algorithm processes any tree in linear time, using a heavy path decomposition, so that subsequent lowest common ancestor queries may be answered in constant time per query. However, their data structure is complex and difficult to implement. Tarjan also found a simpler but less efficient algorithm, based on the union-find data structure, for computing lowest common ancestors of an offline batch of pairs of nodes.

Baruch Schieber and Uzi Vishkin (1988) simplified the data structure of Harel and Tarjan, leading to an implementable structure with the same asymptotic preprocessing and query time bounds. Their simplification is based on the principle that, in two special kinds of trees, lowest common ancestors are easy to determine: if the tree is a path, then the lowest common ancestor can be computed simply from the minimum of the levels of the two queried nodes, while if the tree is a complete binary tree, the nodes may be indexed in such a way that lowest common ancestors reduce to simple binary operations on the indices. The structure of Schieber and Vishkin decomposes any tree into a collection of paths, such that the connections between the paths have the structure of a binary tree, and combines both of these two simpler indexing techniques.

Omer Berkman and Uzi Vishkin (1993) discovered a completely new way to answer lowest common ancestor queries, again achieving linear preprocessing time with constant query time. Their method involves forming an Euler tour of a graph formed from the input tree by doubling every edge, and using this tour to write a sequence of level numbers of the nodes in the order the tour visits them; a lowest common ancestor query can then be transformed into a query that seeks the minimum value occurring within some subinterval of this sequence of numbers. They then handle this range minimum query problem by combining two techniques, one technique based on precomputing the answers to large intervals that have sizes that are powers of two, and the other based on table lookup for small-interval queries. This method was later presented in a simplified form by Michael Bender and Martin Farach-Colton (2000). As had been previously observed by Gabow, Bentley & Tarjan (1984), the range minimum problem can in turn be transformed back into a lowest common ancestor problem using the technique of Cartesian trees.

Further simplifications were made by Alstrup et al. (2004) and Fischer & Heun (2006).

A variant of the problem is the dynamic LCA problem in which the data structure should be prepared to handle LCA queries intermixed with operations that change the tree (that is, rearrange the tree by adding and removing edges) This variant can be solved using O(logN) time for all modifications and queries. This is done by maintaining the forest using the dynamic trees data structure with partitioning by size; this then maintains a heavy-light decomposition of each tree, and allows LCA queries to be carried out in logarithmic time in the size of the tree.

Without preprocessing you can also improve the naïve online algorithm's computation time to O(log h) by storing the paths through the tree using skew-binary random access lists, while still permitting the tree to be extended in constant time (Edward Kmett (2012)). This allows LCA queries to be carried out in logarithmic time in the height of the tree.

Extension to directed acyclic graphs

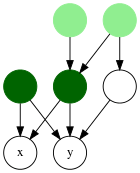

While originally studied in the context of trees, the notion of lowest common ancestors can be defined for directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), using either of two possible definitions. In both, the edges of the DAG are assumed to point from parents to children.

- Given G = (V, E), Aït-Kaci et al. (1989) define a poset (V, ≤) such that x ≤ y iff x is in the reflexive transitive closure of y. The lowest common ancestors of x and y are then the minimum elements under ≤ of the common ancestor set {z ∈ V | x ≤ z and y ≤ z}.

- Bender et al. (2005) gave an equivalent definition, where the lowest common ancestors of x and y are the nodes of out-degree zero in the subgraph of G induced by the set of common ancestors of x and y.

In a tree, the lowest common ancestor is unique; in a DAG of n nodes, each pair of nodes may have as much as n-2 LCAs (Bender et al. 2005), while the existence of an LCA for a pair of nodes is not even guaranteed in arbitrary connected DAGs.

A brute-force algorithm for finding lowest common ancestors is given by Aït-Kaci et al. (1989): find all ancestors of x and y, then return the maximum element of the intersection of the two sets. Better algorithms exist that, analogous to the LCA algorithms on trees, preprocess a graph to enable constant-time LCA queries. The problem of LCA existence can be solved optimally for sparse DAGs by means of an O(|V||E|) algorithm due to Kowaluk & Lingas (2005).

Dash et al. (2013) present a unified framework for pre-processing Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) to compute the least upper bound of two vertices in constant time. Their framework uses adaptive pre-processing where the asymptotic costs depend on the number of non-tree (cross) edges in the DAG. Consequently, it is possible to achieve near-linear pre-processing times for sparse DAGs with constant time LCA look-ups. A library of their work is available for public use at.[1]

Couto et al. (2011) present DiShIn a method that extends the computation of the LCA to all disjunctive ancestors in semantic similarity measures. He defines an ancestor as disjunctive if the difference between the number of distinct paths from the two nodes to that ancestor is different from using any lower common ancestor.

Applications

The problem of computing lowest common ancestors of classes in an inheritance hierarchy arises in the implementation of object-oriented programming systems (Aït-Kaci et al. 1989). The LCA problem also finds applications in models of complex systems found in distributed computing (Bender et al. 2005).

See also

References

- Aho, Alfred; Hopcroft, John; Ullman, Jeffrey (1973), "On finding lowest common ancestors in trees", Proc. 5th ACM Symp. Theory of Computing (STOC), pp. 253–265, doi:10.1145/800125.804056.

- Aït-Kaci, H.; Boyer, R.; Lincoln, P.; Nasr, R. (1989), "Efficient implementation of lattice operations" (PDF), ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 11 (1): 115–146, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.106.4911, doi:10.1145/59287.59293.

- Alstrup, Stephen; Gavoille, Cyril; Kaplan, Haim; Rauhe, Theis (2004), "Nearest Common Ancestors: A Survey and a New Algorithm for a Distributed Environment", Theory of Computing Systems, 37 (3): 441–456, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.76.5973, doi:10.1007/s00224-004-1155-5. A preliminary version appeared in SPAA 2002.

- Bender, Michael A.; Farach-Colton, Martin (2000), "The LCA problem revisited", Proceedings of the 4th Latin American Symposium on Theoretical Informatics, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 1776, Springer-Verlag, pp. 88–94, doi:10.1007/10719839_9, ISBN 978-3-540-67306-4.

- Bender, Michael A.; Farach-Colton, Martín; Pemmasani, Giridhar; Skiena, Steven; Sumazin, Pavel (2005), "Lowest common ancestors in trees and directed acyclic graphs" (PDF), Journal of Algorithms, 57 (2): 75–94, doi:10.1016/j.jalgor.2005.08.001.

- Berkman, Omer; Vishkin, Uzi (1993), "Recursive Star-Tree Parallel Data Structure", SIAM Journal on Computing, 22 (2): 221–242, doi:10.1137/0222017.

- Djidjev, Hristo N.; Pantziou, Grammati E.; Zaroliagis, Christos D. (1991), "Computing shortest paths and distances in planar graphs", Automata, Languages and Programming: 18th International Colloquium, Madrid, Spain, July 8–12, 1991, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 510, Springer, pp. 327–338, doi:10.1007/3-540-54233-7_145, ISBN 978-3-540-54233-9.

- Fischer, Johannes; Heun, Volker (2006), "Theoretical and Practical Improvements on the RMQ-Problem, with Applications to LCA and LCE", Proceedings of the 17th Annual Symposium on Combinatorial Pattern Matching, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 4009, Springer-Verlag, pp. 36–48, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.64.5439, doi:10.1007/11780441_5, ISBN 978-3-540-35455-0.

- Gabow, Harold N.; Bentley, Jon Louis; Tarjan, Robert E. (1984), "Scaling and related techniques for geometry problems", STOC '84: Proc. 16th ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, New York, NY, USA: ACM, pp. 135–143, doi:10.1145/800057.808675, ISBN 978-0897911337.

- Harel, Dov; Tarjan, Robert E. (1984), "Fast algorithms for finding nearest common ancestors", SIAM Journal on Computing, 13 (2): 338–355, doi:10.1137/0213024.

- Kowaluk, Miroslaw; Lingas, Andrzej (2005), "LCA queries in directed acyclic graphs", in Caires, Luís; Italiano, Giuseppe F.; Monteiro, Luís; Palamidessi, Catuscia; Yung, Moti (eds.), Automata, Languages and Programming, 32nd International Colloquium, ICALP 2005, Lisbon, Portugal, July 11-15, 2005, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3580, Springer, pp. 241–248, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.460.6923, doi:10.1007/11523468_20, ISBN 978-3-540-27580-0

- Dash, Santanu Kumar; Scholz, Sven-Bodo; Herhut, Stephan; Christianson, Bruce (2013), "A scalable approach to computing representative lowest common ancestor in directed acyclic graphs" (PDF), Theoretical Computer Science, 513: 25–37, doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2013.09.030, hdl:2299/12152

- Schieber, Baruch; Vishkin, Uzi (1988), "On finding lowest common ancestors: simplification and parallelization", SIAM Journal on Computing, 17 (6): 1253–1262, doi:10.1137/0217079.

- Couto, Francisco; Silva, Mário (2011), "Disjunctive shared information between ontology concepts: application to Gene Ontology", Journal of Biomedical Semantics, 2 (1): 5, doi:10.1186/2041-1480-2-5, PMC 3200982, PMID 21884591

External links

- Lowest Common Ancestor of a Binary Search Tree, by Kamal Rawat

- Python implementation of the algorithm of Bender and Farach-Colton for trees, by David Eppstein

- Python implementation for arbitrary directed acyclic graphs

- Lecture notes on LCAs from a 2003 MIT Data Structures course. Course by Erik Demaine, notes written by Loizos Michael and Christos Kapoutsis. Notes from 2007 offering of same course, written by Alison Cichowlas.

- Lowest Common Ancestor in Binary Trees in C. A simplified version of the Schieber–Vishkin technique that works only for balanced binary trees.

- Video of Donald Knuth explaining the Schieber–Vishkin technique

- Range Minimum Query and Lowest Common Ancestor article in Topcoder

- Documentation for the lca package for Haskell by Edward Kmett, which includes the skew-binary random access list algorithm. Purely functional data structures for on-line LCA slides for the same package.