Loughor Castle

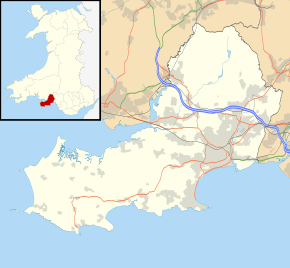

Loughor Castle is a ruined, medieval fortification located in the town of Loughor, Wales. The castle was built around 1106 by the Anglo-Norman lord Henry de Beaumont, during the Norman invasion of Wales. The site overlooked the River Loughor and controlled a strategic road and ford running across the Gower Peninsula. The castle was designed as an oval ringwork, probably topped by wicker fence defences, and reused the remains of the former Roman fort of Leucarum.

| Loughor Castle | |

|---|---|

| Loughor, Wales | |

The ruined stone tower at Loughor Castle | |

Loughor Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.6622°N 4.0774°W |

| Type | Ringwork |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Cadw |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| In use | Tourist attraction |

| Materials | Stone |

Over the next two centuries, the castle was involved in many conflicts. It was attacked and burnt, probably in the Welsh uprising of 1151, and was captured by the forces of Llywelyn the Great in 1215. John de Braose acquired the castle in 1220 and repaired it, constructing a stone curtain wall to replace the older defences. Attacked again in 1251, the castle was reinforced with a stone tower in the second half of the 13th century. It declined in importance during the late-medieval period, and by the 19th century, the castle was ruinous and overgrown with ivy.

In the 21st century, Loughor Castle is controlled by the Welsh heritage agency Cadw and operated as a tourist attraction. The ruined tower and fragments of the curtain wall still survive on top of the ringwork's earthwork defences, which now resemble a motte, or mound, and are part of the Loughor Castle Park.

History

1st–4th centuries

Loughor Castle is located 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) west of Swansea in South-West Wales, overlooking the River Loughor.[1] The site was first used by the Romans for a military fort, one of a sequence running across South-West Wales.[2] The fort, Leucarum, took its name from the Celtic name for the River Loughor.[3] Its location provided good visibility across the region and enabled it to support naval units operating in the Bristol Channel. It also controlled a ford across the River Loughor; this ford had probably emerged by the time of the Roman period, and was passable at high tide.[4] The fort was built around 75 AD and was used until the middle of the 2nd century; it was then reoccupied by the Romans during the late 3rd and early 4th century, before being abandoned by the military.[5]

11th–12th centuries

The Normans began to make incursions into South Wales from the late-1060s onwards, pushing westwards from their bases in recently occupied England.[6] Their advance was marked by the construction of castles, frequently on old Roman sites, for example those at Cardiff, Pevensey and Portchester, and the creation of regional lordships.[7] Reusing former Roman sites in this way produced considerable savings in the manpower required to construct the large earth fortifications of the early castles.[8]

Loughor Castle was constructed on the western edge of the Welsh commote, or land unit, of Gwyr.[1] The castle was built shortly after 1106, when Henry de Beaumont, the Earl of Warwick, was given the Gower Peninsula by Henry I.[9] The Anglo-Norman colonisation of the region followed, with Gower becoming a Marcher territory, enjoying extensive local independence.[10] Loughor Castle was strategically important because it controlled the main road running through Gywr from Beaumont's main base at Swansea Castle, and was a valuable coastal port.[11] The castle took its name from a corruption of the title of the Roman fort.[11]

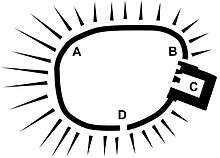

In the 12th century, the castle would have been defended on its south side by a steep slope and the marshy ground running along the river.[11] It was designed as an oval ringwork, which today is around 21 metres (69 ft) by 18 metres (59 ft) across and 12 metres (39 ft) high, protected by a ditch 5 metres (16 ft) wide and 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) deep.[12] The Roman fort in this corner was only visible as earthworks in the 12th century, and the builders used part of these in the construction of the ringwork.[13] The ringwork was made up of a core of river gravel and coarse sand, with finer sand and clay forming the surface layer.[14] The ringwork had a protective wicker fence around the top of the earthworks and possibly some form of early stone or wooden tower, with a gateway just to the north side of it.[15] It is unclear what kind of buildings were constructed inside the ringwork, although a kitchen was certainly built on the east side of the enclosure.[11]

The first half of the 12th century was a violent period in Gower, with extensive fighting occurring between the Anglo-Normans and the local Welsh.[16] Loughor Castle was attacked and burnt down around the middle of the century, probably as a part of a Welsh rebellion that devastated the area in 1151.[15] Henry II and the Welsh prince Rhys ap Gruffydd later agreed peace terms, and the castle was rebuilt.[16] The inside of the ringwork was partially filled by debris during the 1151 attack, and at some point in the next few decades the bank of the ringwork was also deliberately widened inwards in places, allowing buildings to be constructed on it.[17] These changes started the process of filling in the middle of the ringwork which led to the castle today having a mound, or motte-like, appearance.[9]

At around the end of the 12th century, two stone buildings were constructed in the centre of the ringwork, one of them being around 8 metres (26 ft) by 4.5 metres (15 ft).[18] The castle probably passed into the control of the King of England at around this time, in lieu of debts owed by the Earl of Warwick.[18] War broke out again across South-West Wales in 1189 on the death of Henry II, as Rhys and his sons attempted to reclaim the region.[16]

13th–14th centuries

Gower continued to see extensive fighting in the 13th century. Loughor Castle was given by King John to his ally William de Braose in 1203; William was a powerful Marcher Lord, and related to Rhys ap Gruffudd and his extended family.[19] In 1208, however, John and William argued; their relationship broke down and the king attempted to confiscate Loughor and William's other lands in the region.[19] William allied himself with the Welsh prince Llywelyn the Great and war broke out.[18] William died in 1211, but his son, Reginald, continued fighting and married Gwladus, Llywelyn's daughter.[19] In 1215, the castle was captured by Llywelyn's forces and control of Gower was granted to Reginald.[20] Two years later, however, Reginald made peace with the English Crown and Llywelyn removed him from power, replacing him with the Welsh prince Rhys Gryg.[21] Contemporary chroniclers recorded that Rhys Gryg deliberately destroyed all the castles in Gower as part of his campaign to dominate the area.[22]

Llyweyln married another of his daughters, Margaret, to Reginald's nephew, John de Braose, and in 1220 Llyweyln gave him Gower and Loughor Castle, which John appears to have set about repairing.[20] As part of this work, a stone curtain wall was built around the castle.[9] This included a sally port on the north side of the castle.[18]

In 1232 the castle was inherited by John's son, William de Braose, and in turn his son, also called William.[23] In the second half of the century, Wales saw a renewal of fighting, and the castle was attacked again in 1251.[9] The decision was taken to improve the castle's defences and, as part of this, a square, stone tower was added to the castle to provide living accommodation, with three chambers, the first floor containing a garderobe and a fireplace.[24] A gateway was constructed through the curtain wall just to the south of the tower.[23] Two further stone buildings were constructed within the castle walls.[18]

In 1302, William de Braose granted the Loughor estate to his seneschal, John Yweyn, for life, in exchange for an annual fee of a greyhound collar.[25] On John Yweyn's death in 1322 the lands were seized by John de Mowbray, William's son-in-law.[25] John was involved in the rebellion against Edward II, however, and was executed later in 1322; John Yweyn's next of kin, Alice Roculf, successfully appealed to the king and was granted the lands instead.[25] Edward fell from power in 1327, and the Loughor lands were granted to John de Mowbray's son, John.[25]

15th–21st centuries

The importance of Loughor Castle and the surrounding town declined in the late-medieval period, and by the 19th century the castle had been ruined for many years and was covered in ivy.[26] The castle was painted by the artist William Butler in the 1850s, who depicted the ruins alongside the local industries and the new railway line that had been cut through the remains of the former Roman fort.[27]

In the 1940s, the south-east corner of the castle tower collapsed; the corner fell to the ground intact and because of its archaeological value it was decided to leave the fallen stonework in place on the ground, rather than risk further damaging it by removing it.[23] In 1946 the castle was given to the Ministry of Works, and is now in the control of the Welsh heritage agency Cadw and operated as a tourist attraction.[11] The castle sits within the grounds of the small Loughor Castle Park.[28]

Archaeological investigations were carried out between 1969–71 and in 1973.[11] The castle is protected as a scheduled monument under UK law. Much of the curtain wall has been stolen and destroyed since the medieval period, although fragments remain up to 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) high, and the ruins of the tower remain a prominent feature of the local area.[18]

Notes

- Lewis 1974, p. 147

- Ling 1971, pp. 45–46

- Lewis 1974, pp. 148–149

- Lewis 1974, pp. 147–148; Ling 1971, pp. 45–46

- Ling 1971, p. 48

- Carpenter 2004, p. 110

- Prior 2006, p. 141; Carpenter 2004, p. 110; Lewis 1974, p. 149

- Higham & Barker 2004, p. 200

- Lewis 1973, p. 61; Lewis 1974, p. 148

- Davies 1990, p. 12

- Lewis 1974, p. 148

- Lewis 1974, pp. 149–152

- Lewis 1974, p. 149

- Lewis 1974, p. 152

- Lewis 1973, p. 61; Lewis 1974, p. 152

- Bartlett 2004, p. 71

- Lewis 1973, p. 61; Lewis 1974, p. 154

- Lewis 1974, p. 156

- Bartlett 2004, p. 72

- Lewis 1974, p. 156; Bartlett 2004, p. 73

- Bartlett 2004, p. 73

- Davies 1990, p. 42

- Lewis 1974, p. 157

- Lewis 1973, p. 61; Lewis 1974, p. 157.

- Charles & Emanuel 1953, p. 65

- Nicholas 1874, p. 55; Samuel Lewis (1849). "Llowes – Lythan's, St., A Topographical Dictionary of Wales". British History Online. pp. 172–179. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- "Loughor, Castle & Town – William Butler". SwanseaHeritage.net. Archived from the original on 20 May 2005. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- "Loughor Castle". City and Council of Swansea. 4 May 2012. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Robert J. (2004). The Hanged Man: A Story of Miracle, Memory, and Colonialism in the Middle Ages. Princeton, US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691117195.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carpenter, David (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: the Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London, UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014824-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charles, B. G.; Emanuel, H. D. (1953). "Welsh Records in the Hereford Capitular Archives". National Library of Wales Journal. 8 (1): 59–73.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davies, R. R. (1990). Domination and Conquest: The Experience of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, 1100–1300. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521029773.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Higham, Robert; Barker, Philip (2004). Timber Castles. Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 9780859897532.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, J. M. (1973). "Archaeological Notes". Morgannwg. 17: 60–62.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, J. M. (1974). "Recent Excavations at Loughor Castle (South Wales)". Château Gaillard: Etudes de castellologie médiévale. 7: 147–157.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ling, Roger (1971). "The Roman Fort at Loughor, 1970–1971". Gower: The Journal of the Gower Society. 22: 44–51.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicholas, Thomas (1874). The History and Antiquities of Glamorganshire and its families. London, UK: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 58881111.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prior, Stuart (2006). A Few Well-Positioned Castles: The Norman Art of War. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 9780752436517.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)