Lottia alveus

Lottia alveus, the eelgrass limpet or bowl limpet, was a species of sea snail or small limpet, a marine gastropod mollusk in the family Lottiidae, the Lottia limpets, a genus of true limpets. This species lived in the western Atlantic Ocean.

| Lottia alveus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Family: | Lottiidae |

| Genus: | Lottia |

| Species: | †L. alveus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Lottia alveus (Conrad, 1831) | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

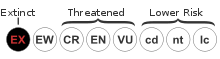

The eelgrass limpet now appears to be totally extinct, but up until the late 1920s, this species was apparently quite common, and was easy to find at low tide in eelgrass beds, in many sheltered localities on the northeastern seaboard of North America.

Distribution before extinction

This limpet was found from Labrador, Canada, as far south as New York.

It supposedly became extinct 60 years before its extinction was noticed (Fall, 2005)

Habitat

This small limpet used to live on the blades of Zostera marina, a species of seagrass.

Cause of extinction

The extinction of Lottia alveus does not seem to have been caused directly by human interference. This small limpet disappeared from the fauna because of a sudden catastrophic collapse of the populations of the eelgrass plant, Zostera marina, which was its sole habitat and food source. In the early 1930s, the seagrass beds all along that part of the coastline were decimated by "wasting disease", which was caused by a slime mold of the genus Labyrinthula.[6][7][8] Some colonies of Zostera marina lived in brackish water, and these areas served as refugia for the eelgrass since the wasting disease did not spread to brackish water. The eelgrass was thus able to survive the catastrophic impact of the disease. The limpet however was unable to tolerate anything but normal salinity seawater, and therefore it did not live through the crisis.[8]

References

- COSEWIC. 2005. Canadian Species at Risk. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 64 pp., page 6.

- Bouchet, P. 1996. Lottia alveus. In: IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 27 September 2008.

- Rosenberg, G. "Lottia alveus (Conrad, 1831)". Malacolog Version 4.1.1 A Database of Western Atlantic Marine Mollusca. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Conrad, T.A. (1831). "Description of fifteen new species of Recent and three fossil shells, chiefly from the coast of the United States". Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 6: 256–268.

- Dall, W.H. (1921). "Summary of the marine shellbearing mollusks of the northwest coast of America, from San Diego, California, to the Polar Sea, mostly contained in the collection of the United States National Museum, with illustrations of hitherto unfigure species". Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 112 (i–iii): 1–217.

- Short, F.T.; Muehlstein, L.K.; Porter, D. (1987). "Eelgrass wasting disease: cause and recurrence of a marine epidemic". Biological Bulletin. 173 (3): 557–562. doi:10.2307/1541701. JSTOR 1541701. PMID 29320228.

- Short, F.T.; Ibelings, B.W.; den Hartog, C. (1988). "Comparison of a current eelgrass disease to the wasting disease of the 1930s". Aquatic Botany. 30 (4): 295–304. doi:10.1016/0304-3770(88)90062-9.

- Carlton, J.; Vermeij, G.J.; Lindberg, D.R.; Carlton, D.A.; Dudley, E.C. (1991). "The first historical extinction of a marine invertebrate in an ocean basin: the demise of the eelgrass limpet Lottia alveus". Biological Bulletin. 180 (1): 72–80. doi:10.2307/1542430. JSTOR 1542430. PMID 29303643.

External links

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070510162140/http://biology.mcgill.ca/undergra/c465a/biodiver/2000/eelgrass-limpet/eelgrass-limpet.htm

- The First Historical Extinction of a Marine Invertebrate in an Ocean Basin: The Demise of the Eelgrass Limpet Lottia alveus

- http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=175