Lurs

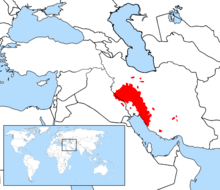

Lurs (Luri: لوریا/لُرو) or Lurish people are an Iranian people living mainly in western and south-western Iran. Their population is estimated at around five million. They occupy Lorestan, Kohkiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Khuzestan and Fars (especially Lamerd, Mamasani and Rostam), Bushehr, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Hamadan, Ilam, and Isfahan provinces.[4] The Lur people mostly speak the Luri language, a Southwestern Iranian language related to Persian. According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the Luri language is the closest living language to Archaic and Middle Persian.[5] According to the linguist Don Still, Lori-Bakhtiari like Persian is derived directly from Old Persian.[6] Michael M. Gunter states that Lur people are closely related to the Kurds but that they "apparently began to be distinguished from the Kurds 1,000 years ago."[7]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 5,000,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 517,000[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Luri and Persian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Shi'a Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Persians, Kurds, Laks, and Other Iranian peoples | |

Lurs are the demographic majority of the provinces of Kohkiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Lorestan, and Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari. Half of Khuzestan's population is Lur and 30% of Bushehr's population is Lur.[8]

Language

Luri is a Western Iranian language continuum spoken by the Lurs in Western Asia. Luri language forms various language groups comprising Central Luri, Bakhtiari,[9][10] and the Southern Luri.[9][10]

Richard N. Frye wrote that "the Lurs and their dialects are closely related to the Persians of Fars province, and naturally belong to the southwestern branch of the Iranian peoples..."[11] The Luri language is divided into two main groups:

- The dialect spoken in Luri-i buzurg (Greater Lur) which is closely related to Persian. This dialect is spoken by the inhabitants of Bakhtiari, Kuh-Gilu-Boir Ahmed, in the north and east of Khuzistan, in the Mamasani district of Fars, and in some areas of Bushehr province.

- The dialect spoken in Lur-i-Kuchek (Lesser Lor) which is closely related to southern Kurdish, with has some similarities to Persian. This dialect is spoken in Luristan, several districts of Hamadan (Malayer, Nahavand, Towisarkan) and by the inhabitants of south and southwest Ilam and northern part of Khuzestan province.

- There is a third group of Luri people who speak northern Luri; they are ethnically part of Lur-e-kuchak, but dialectically part of Lur-e-bozorg.

History

Lurs are a mixture of aboriginal Iranian tribes, originating from Central Asia and the pre-Iranic tribes of western Iran, such as the Kassites (whose homeland appears to have been in what is now Lorestan) and Gutians. In accordance to geographical and archaeological matching, some historians argue that the Elamites to be the Proto-Lurs, whose language became Iranian only in the Middle Ages.[12][13] Michael M. Gunter states that they are closely related to the Kurds but that they "apparently began to be distinguished from the Kurds 1,000 years ago." He adds that the Sharafnama of Sharaf Khan Bidlisi "mentioned two Lur dynasties among the five Kurdish dynasties that had in the past enjoyed royalty or the highest form of sovereignty or independence."[7] In the Mu'jam Al-Buldan of Yaqut al-Hamawi mention is made of the Lurs as a Kurdish tribe living in the mountains between Khuzestan and Isfahan. The term Kurd according to Richard Frye was used for all Iranian nomads (including the population of Luristan as well as tribes in Kuhistan and Baluchis in Kirman) for all nomads, whether they were linguistically connected to the Kurds or not.[14]

Genetics

Considering their NRY variation, the Lurs are distinguished from other Iranian groups by their relatively elevated frequency of Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b (specifically, of subclade R1b1a2a-L23).[15] Together with its other clades, the R1 group comprises the single most common haplogroup among the Lurs.[15][16] Haplogroup J2a (subclades J2a3a-M47, J2a3b-M67, J2a3h-M530, more specifically) is the second most commonly occurring patrilineage in the Lurs and is associated with the diffusion of agriculturalists from the Neolithic Near East c. 8000-4000 BCE.[16][17][18][19] Another haplogroup reaching a frequency above 10% is that of G2a, with subclade G2a3b accounting for most of this.[20] Also significant is haplogroup E1b1b1a1b, for which the Lurs display the highest frequency in Iran.[20] Lineages Q1b1 and Q1a3 present at 6%, and T at 4%.[20]

Culture

The authority of tribal elders remains a strong influence among the nomadic population. It is not as dominant among the settled urban population. As is true in Kurdish societies, Lur women have much greater freedom than women in other groups within the region. The women have had much freedom to participate in different social activities, to wear female diverse clothing and to sing and dance in different ceremonies.[21] Bibi Maryam Bakhtiari, and Qadam Kheyr are two notable Luri women from Iran.[22][23] Luri music, Luri clothing and Luri folk dances are from the most distinctive ethno-cultural characteristics of this ethnic group.

Many Lurs are small-scale agriculturists and shepherds. A few Lurs are also traveling musicians. Lurish textiles and weaving skills are highly esteemed for their workmanship and beauty.[24]

See also

References

- "Iran". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- "Iran" (PDF). New America Foundation. June 12, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- "Luri". PeopleGroups.org. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "The Lurs of Iran". Cultural Survival. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- C.S. Coon, "Iran:Demography and Ethnography" in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume IV, E. J. Brill, pp 10,8.

- Don Stillo, "Isfahan-Provincial Dialects" in Encyclopedia Iranica. Excerpt: "While the modern SWI languages, for instance, Persian, Lori-Bak_tia-ri and others, are derived directly from Old Persian through Middle Persian/Pahlavi."

- Gunter, Michael M. (2011). Historical Dictionary of the Kurds (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0810867512.

- "History and cultural relations - Lur". Everyculture.com. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- Erik John Anonby (2003). "Update on Luri: How many languages?" Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Third Series), 13, pp 171-197. doi:10.1017/S1356186303003067.

- G. R. Fazel, "Lur", in Muslim Peoples: A World Ethnographic Survey, ed. R. V. Weekes (Westport, 1984), pp. 446–447

- Frye, Richard N. (1983). Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft, Part 3. 7. Beck. p. 29. ISBN 978-3406093975.

- Edwards, I.E.S.; Gadd, C.J.; Hammond, G.L. (1971). The Cambridge Ancient History (2nd ed.). Camberidge University Press. p. 644. ISBN 9780521077910.

- Potts, D.S (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State (Cambridge World Archaeology) (2nd ed.). Camberidge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780521564960.

- Richard Frye,"The Golden age of Persia", Phoenix Press, 1975. Second Impression December 2003. pp 111: "Tribes always have been a feature of Persian history, but the sources are extremely scant in reference to them since they did not 'make' history. The general designation 'Kurd' is found in many Arabic sources, as well as in Pahlavi book on the deeds of Ardashir the first Sassanian ruler, for all nomads no matter whether they were linguistically connected to the Kurds of today or not. The population of Luristan, for example, was considered to be Kurdish, as were tribes in Kuhistan and Baluchis in Kirman"

- Grugni, V; Battaglia, V; Hooshiar Kashani, B; Parolo, S; Al-Zahery, N; et al. (2012). "Ancient Migratory Events in the Middle East: New Clues from the Y-Chromosome Variation of Modern Iranians". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e41252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041252. PMC 3399854. PMID 22815981.

- Wells, R. Spencer; et al. (2001). "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (18): 10244–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- Semino O, Passarino G, Oefner P J, Lin A A, Arbuzova S, Beckman L E, de Benedictis G, Francalacci P, Kouvatsi A, Limborska S, et al. (2000) Science 290:1155–1159

- Underhill P A, Passarino G, Lin A A, Shen P, Foley R A, Mirazon-Lahr M, Oefner P J, Cavalli-Sforza L L (2001) Ann Hum Genet 65:43–62

- Semino, Ornella; Magri, Chiara; Benuzzi, Giorgia; Lin, Alice A.; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Battaglia, Vincenza; MacCioni, Liliana; Triantaphyllidis, Costas; et al. (2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- Grugni, V; Battaglia, V; Hooshiar Kashani, B; Parolo, S; Al-Zahery, N; et al. (2012). "Ancient Migratory Events in the Middle East: New Clues from the Y-Chromosome Variation of Modern Iranians". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e41252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041252. PMC 3399854. PMID 22815981.

- Edmonds, Cecil (2010). East and West of Zagros: Travel, War and Politics in Persia and Iraq 1913-1921. p. 188. ISBN 9789004173446.

- F.Stark, 1934,The Valleys of the Assassins: and Other Persian Travels, Modern library

- Garthwaite, Gene Ralph (1996). Bakhtiari in the mirror of history. Ānzān. p. 187. ISBN 9789649046518.

- Winston, Robert, ed. (2004). Human: The Definitive Guide. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 409. ISBN 0-7566-0520-2.