Loriini

Loriini is a tribe of small to medium-sized arboreal parrots characterized by their specialized brush-tipped tongues for feeding on nectar of various blossoms and soft fruits, preferably berries. The species form a monophyletic group within the parrot family Psittacidae. The group consist of the lories and lorikeets. Traditionally, they were considered a separate subfamily (Loriinae) from the other subfamily (Psittacinae) based on the specialized characteristics, but recent molecular and morphological studies show that the group is positioned in the middle of various other groups. They are widely distributed throughout the Australasian region, including south-eastern Asia, Polynesia, Papua New Guinea, Timor Leste and Australia, and the majority have very brightly coloured plumage.

| Loriini | |

|---|---|

_(5981479349).jpg) | |

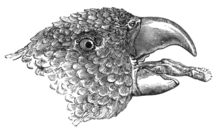

| Phigys solitarius in Ornithological miscellany 1876 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittaculidae |

| Subfamily: | Loriinae |

| Tribe: | Loriini Selby, 1836 |

| Genera | |

|

Chalcopsitta | |

Etymology

The usage of the terms "lory" and "lorikeet" is subjective, like the usage of "parrot" and "parakeet". Species with longer tapering tails are generally referred to as "lorikeets", while species with short blunt tails are generally referred to as "lories".[1]

Taxonomy

Traditionally, lories and lorikeets have either been classified as the subfamily, Loriinae, or as a family on their own, Loriidae,[2] but they are currently classified as a tribe. Neither traditional view is confirmed by molecular studies. Those studies show that the lories and lorikeets form a single group, closely related to the budgerigar and the fig parrots (Cyclopsitta and Psittaculirostris).[3][4][5][6][7]

Two main groups are recognized within the lories and lorikeets. The first consist of the genus Charmosyna[3][4] and the closely related Pacific Ocean genera Phigys and Vini.[3] All remaining genera, except Oreopsittacus are in the second group.[3][4] The position of Oreopsittacus is unknown, although one study suggests it could be a third group next to the other two.[7]

Species

Classification of parrots in the subfamily, Loriinae:

| Image | Genus | Living Species |

|---|---|---|

-7.jpg) | Chalcopsitta Bonaparte, 1850 |

|

| Eos Wagler, 1832 |

|

| Pseudeos J.L. Peters, 1935 |

|

| Trichoglossus Stephens, 1826 |

|

| Psitteuteles Bonaparte, 1854(sometimes classified in the Genus Trichoglossus) |

|

| Lorius Vigors, 1825 |

|

| Phigys G.R. Gray, 1870 |

|

| Vini Lesson, 1833 |

|

| Glossopsitta Bonaparte, 1854 |

|

.jpg) | Parvipsitta Mathews, 1916 |

|

| Charmosyna Wagler, 1832 |

|

_-captive-8a-4c.jpg) | Oreopsittacus Salvadori, 1877 |

|

| Neopsittacus Salvadori, 1875 |

| |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny of the genera of lories and lorikeets with their closest relatives, the fig parrots (Cyclopsitta and Psittaculirostris) and budgerigar, based on the available literature[3][4][5][6][7] |

Morphology

Lories and lorikeets have specialized brush-tipped tongues for feeding on nectar and soft fruits. They can feed from the flowers of about 5,000 species of plants and use their specialized tongues to take the nectar. The tip of their tongues have tufts of papillae (extremely fine hairs), which collect nectar and pollen.

The multi-coloured rainbow lorikeet was one of the species of parrots appearing in the first edition of The Parrots of the World and also in John Gould's lithographs of the Birds of Australia. Then and now, lories and lorikeets are described as some of the most beautiful species of parrot.

Diet

In the wild, rainbow lorikeets feed mainly on pollen and nectar, and possess a tongue adapted especially for their particular diet. Many fruit orchard owners consider them a pest, as they often fly in groups and strip trees containing fresh fruit. They are also frequent visitors at bird feeders that supply lorikeet-friendly treats, such as store-bought nectar, sunflower seeds, and fruits such as apples, grapes and pears.[10] Occasionally they have been observed feeding on meat.[11]

Conservation

_-drinking.jpg)

The ultramarine lorikeet is endangered. It is now one of the 50 rarest birds in the world. The blue lorikeet is classified as vulnerable. The introduction of European rats to the small island habitats of these birds is a major cause of their endangerment.[12] Various conservation efforts have been made to relocate some of these birds to locations free of predation and habitat destruction.

In literature

A "Lory" famously appears in Chapter III of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Alice argues with the Lory about its age.

Gallery

%2C_Gembira_Loka_Zoo%2C_Yogyakarta_2015-03-15_03.jpg)

Green-naped lorikeet (subspecies of rainbow lorikeet)

Green-naped lorikeet (subspecies of rainbow lorikeet)

%2C_Gembira_Loka_Zoo%2C_Yogyakarta%2C_2015-03-15_03.jpg)

Australian rainbow lorikeet (subspecies of rainbow lorikeet)

Australian rainbow lorikeet (subspecies of rainbow lorikeet) Black-capped lory at the Cincinnati Zoo

Black-capped lory at the Cincinnati Zoo

References

- Low, Rosemary (1998). Hancock House Encyclopedia of the Lories. Hancock House. pp. 85–87. ISBN 0-88839-413-6.

- Forshaw, Joseph M.; Cooper, William T. (1981) [1973, 1978]. Parrots of the World (corrected second ed.). David & Charles, Newton Abbot, London. ISBN 0-7153-7698-5.

- Wright, T.F.; Schirtzinger E. E.; Matsumoto T.; Eberhard J. R.; Graves G. R.; Sanchez J. J.; Capelli S.; Muller H.; Scharpegge J.; Chambers G. K.; Fleischer R. C. (2008). "A Multilocus Molecular Phylogeny of the Parrots (Psittaciformes): Support for a Gondwanan Origin during the Cretaceous". Mol Biol Evol. 25 (10): 2141–56. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn160. PMC 2727385. PMID 18653733.

- Astuti, Dwi; Azuma, Noriko; Suzuki, Hitoshi; Higashi, Seigo (2006). "Phylogenetic relationships within parrots (Psittacidae) inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene sequences". Zoological Science. 23 (2): 191–98. doi:10.2108/zsj.23.191. hdl:2115/54809. PMID 16603811.

- de Kloet, RS; de Kloet SR (2005). "The evolution of the spindlin gene in birds: Sequence analysis of an intron of the spindlin W and Z gene reveals four major divisions of the Psittaciformes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 36 (3): 706–721. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.03.013. PMID 16099384.

- Tokita, M; Kiyoshi T; Armstrong KN (2007). "Evolution of craniofacial novelty in parrots through developmental modularity and heterochrony". Evolution & Development. 9 (6): 590–601. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00199.x. PMID 17976055. Archived from the original on 2012-10-05.

- Christidis, L., L.; Schodde, R.; Shaw, D. D.; Maynes, S. F. (1991). "Relationships among the Australo-Papuan parrots, lorikeets, and cockatoos (Aves, Psittaciformes) - protein evidence". Condor. 93 (2): 302–17. doi:10.2307/1368946. JSTOR 1368946.

- "UNEP-WCMC Species Database Lorius amabilis". Unep-wcmc.org. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- "UNEP-WCMC Species Database Lorius tibialis". Unep-wcmc.org. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- "Rainbow Lorikeet / Rainbow Lory aka Green Naped Lory / Lorikeet". www.beautyofbirds.com. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- "Meat-eating rainbow lorikeets puzzle bird experts". ABC News. 2015-03-23. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- Steadman D, (2006). Extinction and Biogeography in Tropical Pacific Birds, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77142-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Loriinae. |

- ARKive - images and movies of the blue lorikeet/tahitian lory (Vini peruviana)

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- "Lory". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Lory". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Lory". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.