Loop (music)

In electroacoustic pop, rock, and other kinds of music, a loop is a repeating section of sound material. Short sections of material can be repeated to create ostinato patterns. Longer sections can also be repeated: for example, a player might loop what he plays on an entire verse of a song in order to then play along with it, accompanying himself. Loops can be created using a wide range of music technologies including turntables, digital samplers, looper pedals, synthesizers, sequencers, drum machines, tape machines, and delay units, and they can be programmed using computer music software.

Royalty-free loops can be purchased and downloaded for music creation from companies like The Loop Loft, Native Instruments, Splice and Output.

Loops are supplied in either MIDI or Audio file formats such as WAV, REX2, AIFF and MP3. Musicians "play" loops by triggering the start of the musical sequence by utilizing a MIDI controller such as an Ableton Push or a Native Instruments MASCHINE.

Definitions

- "Loops are short sections of tracks (probably between one and four bars in length), which you believe might work being repeated." A loop is not "any sample, but...specifically a small section of sound that's repeated continuously." Contrast with a one-shot sample (Duffell 2005, p. 14).

- "A loop is a sample of a performance that has been edited to repeat seamlessly when the audio file is played end to end" (Hawkins 2004, p. 10).

- "A drum loop is technically a short recording of multiple drum materials which has been edited to loop seamlessly ( to loop smoothly and continuously), a drum loop repeats until an exact duration is satisfied, for example, to break a single loop to another, you might want to use a drum fill which could also be a seamless loop" (Horlaes 2018).

Origins

While repetition is used in the musics of all cultures, the first musicians to use loops were electroacoustic music pioneers such as Pierre Schaeffer, Halim El-Dabh (Holmes 2008, p. 154), Pierre Henry, Edgard Varèse and Karlheinz Stockhausen (Decroupet and Ungeheuer 1998, pp. 110, 118–19, 126). In turn, El-Dabh's music influenced Frank Zappa's use of tape loops in the mid-1960s (Holmes 2008, pp. 153–54).

Terry Riley is a seminal composer and performer of loop- and ostinato-based music who began using tape loops in 1960. For his 1963 piece Music for The Gift he devised a hardware looper that he named the Time Lag Accumulator, consisting of two tape recorders linked together, which he used to loop and manipulate trumpet player Chet Baker and his band. His 1964 composition In C, an early example of what would later be called Minimalism, consists of 53 repeated melodic phrases (loops) performed live by an ensemble. Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band, the b-side of his influential 1969 album A Rainbow In Curved Air uses tape loops of his electric organ and soprano saxophone to create electronic music that contains surprises as well as hypnotic repetition.

Another influential use of tape loops was Jamaican dub music in the 1960s. Dub producer King Tubby used tape loops in his productions, while improvising with homemade delay units. Another dub producer, Sylvan Morris, developed a slapback echo effect by using both mechanical and handmade tape loops. These techniques were later adopted by hip hop musicians in the 1970s (Veal 2007, pp. 187–88). Grandmaster Flash's turntablism is an early example in hip hop.

The use of pre-recorded, digitally-sampled loops in popular music dates back to Japanese electronic music band Yellow Magic Orchestra (Condry 2006, p. 60), who released one of the first albums to feature mostly samples and loops, 1981's Technodelic (Carter 2011). Their approach to sampling was a precursor to the contemporary approach of constructing music by cutting fragments of sounds and looping them using computer technology (Condry 2006, p. 60). The album was produced using Toshiba-EMI's LMD-649 digital PCM sampler, which engineer Kenji Murata custom-built for YMO (Anon. 2011, 140–41).

Modern looping

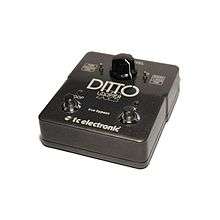

Today, many musicians use digital hardware and software devices to create and modify loops, often in conjunction with various electronic musical effects. A loop can be created by a looper pedal, a device which records the signal from a guitar or other audio source and then plays the recorded passage over and over again (Equipboard Staff 2018).

In the early 1990s, dedicated digital devices were invented specifically for use in live looping, i.e. loops that are recorded in front of a live audience.

Many hardware loopers exist, some in rack unit form, but primarily as effect pedals. The discontinued Lexicon JamMan, Gibson Echoplex Digital Pro, Electrix Repeater, and Looperlative LP1 are 19" rack units. The Boomerang "Rang III" Phrase Sampler, DigiTech JamMan (Ross 2010), Boss RC-300 and the Electro-Harmonix 2880 are examples of popular pedals. As of December 2015, the following pedals are currently in production: TC Ditto, TC Ditto X2, TC Ditto Mic, TC Ditto Stereo, Boss RC-1, Boss RC-3, Boss RC-30, Boss RC-300 and Boss RC-505 (Anon. n.d.).

The musical loop is one of the most important features of video game music. It is also the guiding principle behind devices like the several Chinese Buddhist music boxes that loop chanting of mantras, which in turn were the inspiration of the Buddha machine, an ambient-music generating device. The Jan Linton album "Buddha Machine Music" used these loops along with others created by manually scrolling through C.D.s on a CDJ player (Entropy Records 2011).

Loop-based music software

See also

- Break (music), break beats are drum loops

- Phasing (music)

Bibliography

- Anon. (n.d.). "Looper Pedal: Reviews and Performances". LooperMusic.com (accessed 29 December 2015).

- Anon. (2011). "月刊ロッキンf 1982年3月号 LMD-649の記事 1982". Tokyosky Webmaster's Blog. Rockin'f (March): 140–41.

- Carter, Monica (2011). "It's Easy When You're Big in Japan: Yellow Magic Orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl". The Vinyl District (30 June, accessed 22 July 2011).

- Condry, Ian (2006). Hip-hop Japan: Rap and the Paths of Cultural Globalization. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3892-0. Retrieved 12 June 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Decroupet, Pascal, and Elena Ungeheuer (1998). "Through the Sensory Looking-Glass: The Aesthetic and Serial Foundations of Gesang der Jünglinge", translated by Jerome Kohl. Perspectives of New Music 36, no. 1 (Winter): pp. 97–142. doi:10.2307/833578.

- Equipboard Staff. 2018. "5 Best Looper Pedals for Guitar". Equipboard website (14 August, accessed 18 October 2018)..

- Duffell, Daniel (2005). Making Music with Samples: Tips, Techniques, and 600+ Ready-to-Use Samples. San Francisco: Backbeat. ISBN 0-87930-839-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Entropy Records (2011). "Jan Linton: Buddha Machine Music". Entropy Records. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2011-07-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawkins, Erik (2004). The Complete Guide to Remixing: Produce Professional Dance-Floor Hits on Your Home Computer. Boston: Berklee Press. ISBN 0-87639-044-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2014-06-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horlaes (2018). "Creating a Drum Loop Like a Pro". Exclusivemusicplus (30 October). Retrieved 2018-11-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, Michael (29 July 2010), DigiTech JML2 JamMan Stereo Review: Up to 6 Hours of Looping at the Touch of a Button, Gearwire Forums, archived from the original on November 25, 2012CS1 maint: unfit url (link) Archive from 25 November 2012 (accessed 10 June 2014).

- Veal, Michael E. (2007). Dub: Songscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Baumgärtel, Tilman (2015). Schleifen. Zur Geschichte und Ästhetik des Loops. Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos. ISBN 978-3-86599-271-0. Retrieved 11 July 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)