Longnose stingray

The longnose stingray (Dasyatis guttata) is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, native to the western Atlantic Ocean from the southern Gulf of Mexico to Brazil. Found in coastal waters no deeper than 36 m (118 ft), this demersal species favors muddy or sandy habitats. The longnose stingray is characterized by its angular, rhomboid pectoral fin disc, moderately projecting snout, and whip-like tail with a dorsal keel and ventral fin fold. It typically grows to 1.25 m (4.1 ft) across and is brownish above and light-colored below.

| Longnose stingray | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | D. guttata |

| Binomial name | |

| Dasyatis guttata (Bloch & J. G. Schneider, 1801) | |

| |

| Range of the longnose stingray | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Raja guttata Bloch & J. G. Schneider, 1801 * ambiguous synonym | |

Longnose stingrays feed mainly on bottom-dwelling invertebrates and small bony fishes. Reproduction is aplacental viviparous, with females bearing two litters of 1–2 pups per year. The young are born in relatively fresh water, move into saltier water as juveniles, and then back into fresher water as adults. This species is valued by commercial and recreational fishers in many parts of its range, and utilized for meat, gelatin, oil, and even the aquarium trade. However, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) presently lacks enough specific information on these activities to assess its conservation status.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The first known reference to the longnose stingray was by German naturalist Georg Marcgrave in his 1648 Historia Rerum Naturalis Brasiliae, under the name "iabebirete". Marcgrave's account formed the basis for this species' formal scientific description as Raja guttata, by later German naturalists Marcus Elieser Bloch and Johann Gottlob Schneider in their 1801 Systema Ichthyologiae. Subsequent authors moved this species to the genus Dasyatis. No type specimen has been designated.[2]

Lisa Rosenberger's 2001 phylogenetic analysis, based on morphology, found that the sister species of the longnose stingray is the sharpsnout stingray (D. geijskesi), and that two form a clade with the pale-edged stingray (D. zugei), the pearl stingray (D. margaritella), the sharpnose stingray (Himantura gerrardi), and the smooth butterfly ray (Gymnura micrura, included in the study as an outgroup). These results support the growing consensus that neither Dasyatis nor Himantura are monophyletic.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The longnose stingray can be found in regions ranging from the southern Gulf of Mexico southward to the Brazilian state of Paraná, including the Greater and Lesser Antilles. This bottom-dwelling species inhabits inshore marine and brackish waters from the intertidal zone to a depth of 36 m (118 ft).[1][4] It favors muddy or sandy substrates, and is tolerant of wide variations in salinity.[5]

Description

The longnose stingray has a diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc slightly wider than long, with outer corners forming approximately right angles and gently concave anterior margins converging to an obtuse, moderately projecting snout. The mouth is curved with a median projection in the upper jaw that fits into an indentation in the lower jaw. A row of three papillae are found across the floor of the mouth. There are 34–46 tooth rows in the upper jaw; the teeth have tetragonal bases and blunt crowns in females and juveniles and sharp, pointed cusps in mature males. The pelvic fins are rounded.[4][6]

The slender, whip-like tail is much longer than the disc and usually bears a single serrated stinging spine near the base (some individuals have no spine or more than one). Behind the spine, there is a long, fleshy dorsal keel and a ventral fin fold two-thirds to four-fifths as high as the tail. A row of small, blunt thorns or tubercles is present along the midline of the back, from between the eyes to the base of the tail spine. Larger rays also gain a mid-dorsal band of heart-shaped, flattened denticles. The coloration is olive, brown, or gray above, sometimes with darker spots, and yellowish to white below; the keel and fin fold on the tail are black.[4][6] This species reaches a maximum known disc width of 2 m (6.6 ft), though 1.25 m (4.1 ft) is more typical.[7] Females grow larger than males.[8]

Biology and ecology

Longnose stingrays seem to occupy basically the same ecological niche as the more northerly Atlantic stingray (D. sabina). Where the ranges of the two species overlap, there is spatial segregation with longnose stingrays being found at depths of 1–15 m (3.3–49.2 ft) and Atlantic stingrays being found at depths of up to 50–60 m (160–200 ft).[9] This species feeds mainly on benthic invertebrates and small bony fishes, often using its pectoral fins to uncover burrowing prey. Its pavement-like teeth enables it to grind up hard-shelled organisms.[5] One study off the Brazilian state of Ceará found that the most common prey taken were holothuriid sea cucumbers, peanut worms, eunicid polychaete worms, bivalves and gastropods, the crustaceans Penaeus and Callinectes, and the grunt Pomadasys corvinaeformis.[1] Known parasites of the longnose stingray include the tapeworms Rhinebothrium margaritense and Rhodobothrium pulvinatum,[10] the isopods Excorallana tricornis and Rocinela signata,[11] and the monogenean Monocotyle guttatae.[12]

In common with other stingrays, the longnose stingray is aplacental viviparous, in which the developing embryos are sustained by yolk and later histotroph ("uterine milk") produced by the mother. Females have a single functional uterus, on the left, and bear two litters of 1–2 pups per year, one around March and the other around November. The gestation period is 5–6 months long with vitellogenesis (yolk formation) occurring at the same time, such as that females can ovulate a new batch of ova and mate again immediately after giving birth.[8][13] Longnose stingrays measure 12.3–15.3 cm (4.8–6.0 in) across at birth.[13] Parturition occurs in water with relatively low salinity, but the young soon move into saltier water (half to full-strength seawater).[14] A known nursery area for this species occurs off the beaches of Caiçara do Norte in northeastern Brazil, where newborns and small juveniles have been reported from water no more than 3 m (9.8 ft) deep from February to October.[13] Very small juveniles have also been observed in tidal pools in Ceará.[1] Males mature at 50–60 cm (20–24 in) across and females at 60–70 cm (24–28 in) across.[15] At the onset of sexual maturation, longnose stingrays move back into water with lower salinities of 20 ppt or less; females over 75 cm (30 in) across are found only in salinities of under 5 ppt.[14]

Human interactions

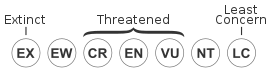

The venomous tail spine of the longnose stingray is potentially dangerous to beachgoers and fishery workers.[4] Throughout its range, this species is taken intentionally and otherwise by commercial fisheries, using gillnets, trawls, and longlines. It is the most commonly caught stingray off the Guyanas and the Brazilian states of Maranhão and Paraíba, and is becoming increasingly important elsewhere.[1][5][15] The longnose stingray is also targeted by recreational surf anglers in Ceará.[1] The meat of its "wings" is highly esteemed and sold fresh, frozen, or salted; this ray is also utilized in the production of gelatin and high-quality oil, and at least five individuals were found in the Ceará aquarium trade from 1995 to 2000.[5][7] The impact of fishing on the longnose stingray population has been little-investigated outside Brazil; as a result the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is not yet able to assess its conservation status beyond Data Deficient.[1]

References

- Rosa, R.S. & M. Furtado (2016). "Hypanus guttatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T44592A104125099. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T44592A104125099.en.

- Catalog of Fishes (Online Version) Archived 2015-05-03 at the Wayback Machine. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved on January 15, 2010.

- Rosenberger, L.J.; Schaefer, S. A. (August 6, 2001). Schaefer, S. A. (ed.). "Phylogenetic Relationships within the Stingray Genus Dasyatis (Chondrichthyes: Dasyatidae)". Copeia. 2001 (3): 615–627. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2001)001[0615:PRWTSG]2.0.CO;2.

- McEachran, J.D. & M.R. de Carvalho (2002). "Dasyatidae". In Carpenter, K.E. (ed.). The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Atlantic (Volume 1). Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 562–571. ISBN 92-5-104825-8.

- Léopold, M. (2004). Poissons de mer de Guyane. Editions Quae. pp. 38–39. ISBN 2-84433-135-1.

- McEachran, J.D. & J.D. Fechhelm (1998). Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Myxiniformes to Gasterosteiformes. University of Texas Press. p. 176. ISBN 0-292-75206-7.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2010). "Dasyatis guttata" in FishBase. January 2010 version.

- Yokota, L. & R.P. Lessa (2007). "Reproductive biology of three ray species: Gymnura micrura (Bloch & Schneider, 1801), Dasyatis guttata (Bloch & Schneider, 1801) and Dasyatis marianae Gomes, Rosa & Gadig, 2000, caught by artisanal fisheries in Northeastern Brazil". Cahiers de Biologie Marine. 48: 249–257.

- Castro-Aguirre, J.L. & H.E. Pérez (1996). Catálogo Sistemático de las Rayas y Especies Afines de México: Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii: Rajiformes: Batoideiomorpha. UNAM. p. 44. ISBN 968-36-5623-4.

- Mayes, M.A. & D.R. Brooks (1981). "Cestode parasites of some Venezuelan stingrays". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 93 (4): 1230–1238.

- Williams, E.H. (Jr.); L. Bunkley-Williams & C.J. Sanner (1994). "New host and locality records for copepod and isopod parasites of Colombian marine fishes". Journal of Aquatic Animal Health. 6 (4): 362–364. doi:10.1577/1548-8667(1994)006<0362:NHALRF>2.3.CO;2.

- Portes Santos, C.; A.L. Santos & D.I. Gibson (February 2006). "A new species of Monocotyle Taschenberg, 1878 (Monogenea: Monocotylidae) from Dasyatis guttata (Dasyatidae)". Journal of Parasitology. 92 (1): 21–24. doi:10.1645/GE-603R.1.

- Yokota, L. & R.P. Lessa (March 2006). "A nursery area for sharks and rays in northeastern Brazil". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 75 (3): 349–360. doi:10.1007/s10641-006-0038-9.

- Thorson, T.B. (1983). "Observations on the morphology, ecology and life history of the euryhaline stingray, Dasyatis guttata (Bloch and Schneider) 1801". Acta Biologica Venezuelica. 11 (4): 95–126.

- Batista da Silva, G.; T. Holando Basilio; F.C. Pereira Nascimento & A.A. Fonteles-Filho (2007). "Size at first sexual maturity of the sting rays Dasyatis guttata and Dasyatis americana, off Ceara State". Arquivos de Ciencias do Mar. 40 (2): 14–18.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dasyatis guttata. |