Lodovico Buglio

Lodovico Buglio (1606–1682), Chinese name Li Leisi (Chinese: 利類思),[1] was an Italian Jesuit mathematician and theologian, a missionary in China.

Lodovico Buglio | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1606 |

| Died | 1682 (aged 76) |

| Occupation | Italian Jesuit active in China |

Life

Buglio was born at Mineo, Sicily, 26 January 1606. He entered the Society of Jesus, 29 January 1622, and, after a career as a professor of the humanities and rhetoric in the Roman College, asked to be sent to the Chinese mission. Buglio preached the Gospel in the provinces of Sichuan, Fujian, and Jiangxi. He and fellow Jesuit Gabriel de Magalhães were pressed to serve the rebel leader Zhang Xianzhong who had conquered Sichuan in 1644.[2] After Zhang was killed by Hooge, he was taken to Beijing in 1648.[3] Here, after a short captivity, he was left free to exercise his ministry. He suffered in the persecution which was carried on during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor.

Buglio collaborated with Fathers Johann Adam Schall von Bell, Ferdinand Verbiest and Gabriel de Magalhães in reforming the Chinese calendar, and shared with them the confidence of the emperor. He died at Beijing, 7 October 1682, and was given a state funeral.

Works

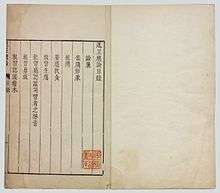

Buglio both spoke and wrote Chinese. A list of his works in Chinese, more than eighty volumes, written for the most part to explain and defend the Christian religion, is given in Carlos Sommervogel. Besides Parts I and III of the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas, he translated into Chinese the Roman Missal (Peking, 1670) the Breviary and the Ritual (ibid, 1674 and 1675). These translations were part of the Jesuit project to introduce a liturgy in Chinese tongue. This plan was approved by Pope Paul V, who, 26 March 1615, granted to regularly ordained Chinese priests the faculty of using their own language in the liturgy and administrations of the sacraments; this faculty was never used. Father Philippe Couplet in 1681 tried to obtain a renewal of it from Rome, but was not successful.

See also

Notes

- He, Jianye (10 January 2008). "Bridging the East and the West: A Case Study of Personal Name Authority Control in Resource Sharing and Overseas Chinese Librarians' Role". Journal of East Asian Libraries: 5.

- Liam Matthew Brokey (2007). Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724. Harvard University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-674-03036-7.

- "Lodovico Buglio: B: By Person: Stories: Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity". bdcconline.net. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

References

- Attribution

![]()